25.03.2024 History of the media

Lietuvos Aidas. History of a Lithuanian Newspaper That Was Born Three Times

Małgorzata Dwornik

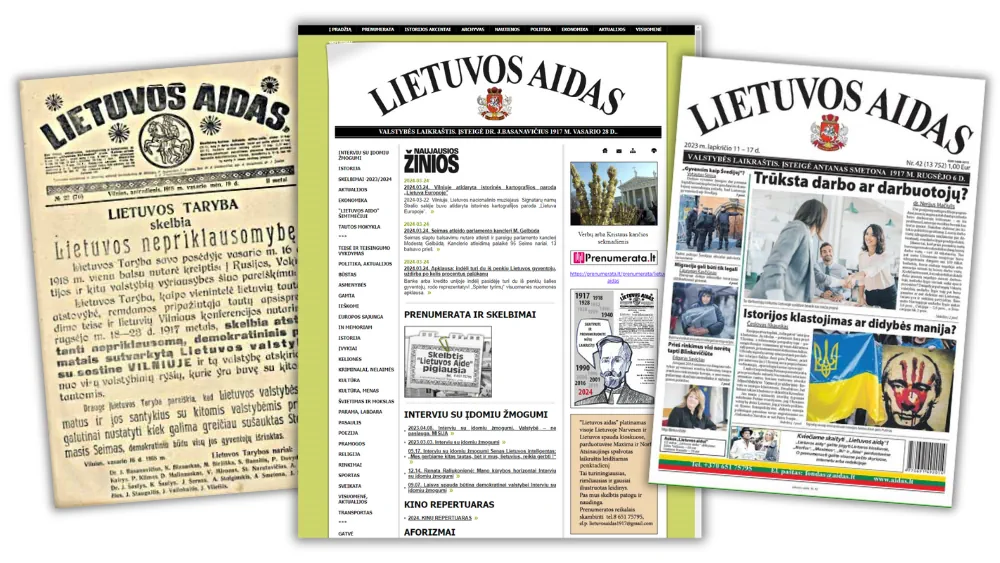

In Lithuania, Lietuvos Aidas is sometimes called "The School of the Nation." This newspaper laid the foundation for free Lithuanian journalism and greatly contributed to the restoration of statehood. It appeared in 1918, disappearing from the market for years at a time, only to return and shape the direction of Lithuanian journalism.

source: public domain/Wikimedia and www.aidas.lt

source: public domain/Wikimedia and www.aidas.ltThe turbulent history of Lithuania dates back to 1009, while its presumed roots trace back to the 3rd century BCE. Over centuries, the Balts, the ancestors of Lithuanians, fought off neighbors coveting their lands. From the 13th century onward, the Teutonic Order was the primary enemy. To fend off invaders, Lithuania allied with Poland, forging a difficult friendship that lasted until the fall of the Kościuszko Uprising in 1794 and the first partition of Poland. This division split Lithuania between Prussia and Russia. Both invaders imposed their rules and laws, oppressing the Lithuanian nation, with Russia being particularly harsh.

Uprisings in Poland, such as the November and January rebellions, inspired similar revolts among Lithuanians but led to increased oppression and growing Polish-Lithuanian antagonism. The outbreak of World War I brought new hopes to the Balts. On September 18, 1917, the Lithuanian National Council, known as Taryba, was established, led by Antanas Smetona.

On September 6, twelve days earlier, Smetona officially launched a Lithuanian-language newspaper, Lietuvos aidas (The Echo of Lithuania), in Vilnius. This publication became the government’s official organ. Since Vilnius was under German administration, the Lithuanian newspaper faced heavy censorship. To appease the occupiers, a German-language version, Litauische Echo, was also published.

Condition: A Priest in the Editorial Team

Although the first issue of The Echo appeared in September, preparations were completed as early as July. While Smetona is recognized as the founder, the idea came from Jonas Basanavičius, a doctor and writer who openly fought for Lithuanian independence. Alongside Smetona and politician Jurgis Šaulys, Basanavičius decided to create a Lithuanian newspaper in December 1916. They applied for German approval, which was granted by Leopold of Bavaria on March 1, 1917, on the condition that at least one editor would be a priest. The formal agreement with the German press office was signed on March 7, and the newspaper`s name, Lietuvos aidas, was registered on March 20.

Since Smetona and Šaulys were busy with political and diplomatic duties, organizing the future national newspaper was entrusted to Basanavičius, who was also expected to serve as editor-in-chief. The first editorial meeting took place on July 15, 1917, at Benediktiny Street 2-2.

The Germans, however, rejected Basanavičius as editor-in-chief, considering him an enemy, and blocked the newspaper`s release. After prolonged negotiations, they approved Smetona for the role, and by then, it was already September.

The first issue of The Echo had four pages with three columns each. The main topic was Karas (war). On the front page, alongside a report from the German headquarters, military plans for the coming days, and current news, there was Primutinis žodis (First Word) – the editor-in-chief’s introductory article. Smetona wrote:

Fully aware of the driving force and significance of this hour, we have gathered global intellectuals and priests, all of us who govern only with the pen, regardless of differing currents and views. Sincere support for our nation and homeland brought us together here. Guided by this thought, we set aside for a moment all that separates us and focused on the shared foundations of work. Moral laws should outweigh state power.

Twice a Week, 15,000 Copies

As a patriotic newspaper, its logo featured Lithuania’s coat of arms – the Vytis (Pahonia). Technical information was placed on either side, separated from the main content by a decorative line. Subsequent pages included national and international news, cultural content, and a few advertisements.

As announced in the editorial, the team consisted of prominent Lithuanian minds responsible for specific sections:

- Mykolas Biržiška, literary historian, led the science and education section

- Peliksas Bugailiškis, lawyer and journalist, handled the Society and Economy sections

- Petras Klimas, lawyer and historian, oversaw everything

- Fr. Juozapas Stankevičius, canon and journalist, ran the Religion and Church section

- Aleksandras Stulginskis, agronomist and political activist (later president of Lithuania), managed Society and Economy

- Dr. Jurgis Šaulys, philosopher and journalist, led the Politics section

- Antanas Žmuidzinavičius, artist and collector, managed the cultural section

Jonas Basanavičius also contributed to the newspaper while organizing the Scientific Society’s Library and participating in the Lithuanian Council, whose meetings were held in The Echo’s editorial office. Initially, The Echo was published twice a week, with a circulation of 15,000 copies. Later, it became tri-weekly, and from October 1, 1918, it turned into a daily (excluding Sundays), gaining a steady readership.

Despite German censorship, the newspaper promoted the idea of restoring Lithuania’s independence. When the Taryba was established less than two weeks later, the Germans did not oppose it (having previously suggested similar solutions to the Lithuanians) but did not lift censorship.

Antanas Smetona, while leading the National Council, did not leave The Echo. He remained the official editor-in-chief, delegating editorial responsibilities to Petras Klimas. As a state organ, Lietuvos aidas published resolutions, laws, and directives. These minor topics took up so much space that two supplements were quickly added:

- Mūsų ūkis (Our Farm) – a weekly focusing on agricultural issues

- Liuosoji valanda (Leisure Hour) – an illustrated monthly dedicated to art and culture

Thanks to a well-organized network of couriers and administration, led by J. Strazdas, The Echo reached every person interested in reading in their native language and believing in Lithuania’s independence. Despite censorship, the content remained comprehensible and resonated with the Balts.

Declaration of Independence and Confiscation of the Issue

At the same time, war raged beyond Lithuania`s borders. Germany, suffering defeats on the fronts, also faced socialist uprisings within its own territory. In Russia, a revolution erupted. Lithuania decided to rise from its knees.

Less than six months after the formation of the Lithuanian Council and the establishment of Lietuvos aidas, on February 16, 1918, the members of Taryba declared Lithuania`s independence and the establishment of the Kingdom of Lithuania. Three days later, on February 19, this solemn act was printed in The Echo. The entire 22nd (70th) issue was devoted to this major event, with signatures from the entire editorial team, who were also signatories of the Act.

Angry Germans confiscated the entire issue of the newspaper. Petras Klimas, anticipating the occupier`s displeasure, hid 60 copies of the issue, which were sent to Germany and Switzerland and reprinted in local newspapers. Meanwhile, printers reproduced the Act and distributed it throughout the country. As the saying goes, the milk had already been spilled, leaving the Germans no choice but to recognize Lithuania`s independence. This occurred on March 21, 1918.

The confiscation of the February 19 issue did not stop the newspaper`s printing. On Wednesday, February 20, the daily was published as usual. War reports and updates on changes in Russia continued. Petras Klimas, a member of Taryba, focused on promoting Lithuania internationally and handed the newspaper`s editorial duties to Liudas Noreika, a lawyer, journalist, and politician.

The advantage of a well-informed citizen is that they see their affairs and public matters of their country not as opposing forces, but as mutual supports. The state and government must reconcile and coordinate the interests of all residents to achieve a unified goal—progress and increased prosperity for the entire nation. This was written by the new editor-in-chief on July 13, 1918, in Lietuvos Aidas. However, this was not an easy task, as censorship persisted, and the Germans closely monitored the writings of Lithuanian journalists.

Issue 214: The First End of Lietuvos Aidas

The editorial team tried to convey information about the rebirth of the nation through articles and columns describing the country`s outskirts, where schools were being established and cultural events organized. The latter half of 1918 was filled with descriptions of new educational courses, nurturing a new generation of Lithuanians.

Noreika led the editorial office until January 1919. During this time, the newspaper had correspondents in nearly every European capital, ensuring that the Iš užsienio (From Abroad) section contained up-to-date news, with a print run reaching 20,000 copies.

In December 1918, when a Bolshevik uprising erupted in Vilnius and later the city was occupied by Poles, the Lithuanian government moved to Kaunas. Unwilling to operate under occupation, Lietuvos Aidas ceased publication, and the editorial office was closed. The last issue, numbered 214, was published on December 31, marking the end of the newspaper`s first chapter.

After the Lithuanian government`s relocation and the closure of Lietuvos Aidas, Nepriklausomoji Lietuva (Independent Lithuania) began to be published in Vilnius, while Lietuva (Lithuania) was issued in Kaunas to replace The Echo. However, it was a far cry from the Vilnius-based publication. Among its contributors was Petras Klimas, but only as an article author.

Return After a Decade

Lietuva was published until January 1928. To the joy of Lithuanians, the 215th issue of Lietuvos Aidas was released on February 1 of the same year. The first editor of the revived Echo was Valentinas Gustainis.

Gustainis was one of the first professional journalists. After completing studies at German and Lithuanian universities, as well as the Sorbonne, he began working for the Vilnius-based Echo at the age of 24. Recognized by senior colleagues, he quickly became a front-page author (The Importance of Patriotism, LA, February 2, 1918) and a political journalist. During the silent years for The Echo, he wrote for Lietuva and was also involved in Lithuanian diplomacy. It was he who persuaded Lithuania`s prime minister and president to revive the former, beloved publication. When he took over the editorial office in February 1928, the Lithuanian president was Antanas Smetona, the founder of the newspaper. The two quickly established a rapport and met weekly.

advertisement

The first revived issue differed in appearance from its predecessor. It lacked the Vytis emblem, and the title was written in a simple, bold font. Below it was the slogan Tautiškas minties dienraštis (Daily National Thought), followed by Isteigtas Wilniuje 1917 Metais (Founded in Vilnius in 1917). On either side of this information were the editorial and advertising sections.

The date line indicated that it was the 1st (215th) issue and the third year of publication. The front page, in addition to the official welcome message to readers, Laisvės ir tiesos keliais (On the Path of Freedom and Truth), featured the editorial article from September 6, 1917, written by Smetona (Pirmutinis žodis).

The newspaper retained the same format but had 10 pages with four columns. In addition to current political, social, and cultural articles, there was an entire advertising section titled Del ko visi privalo skaityti “Lietuvos Aidas” (Why Everyone Should Read Lietuvos Aidas), enriched with humorous texts and drawings. Thus began another chapter in the history of Lithuania`s Echo.

Politics, Entertainment, and Evening Edition

Gustainis led the editorial office for four years. During this time, he collaborated with the elite of Lithuanian bohemia, who often contributed to The Echo. These included the poet Faustas Kirša, playwright Liudas Gira, and ideologist, writer, and literary critic Bronys Raila. A popular section, Kronikos ir Literatūros (Chronicles and Literature), was managed by playwright and prose writer Augustinas Gricius, who also collaborated with the Kaunas-based theater Vilkolakis and the ELTA news agency.

Politics and national issues were priorities in The Echo, but readers also demanded entertainment. These expectations were met when, in 1929, Iliustruota apžvalga (Illustrated Review) began publication, featuring photos, graphics, and satirical drawings. A year later, color was introduced to the newspaper. Advertisements, which had been present from the beginning and helped The Echo stay afloat, began to be printed in solid colors. Red was predominant, but blue and occasionally green were also used.

On December 18, 1932, Valentinas Gustainis stepped down as editor-in-chief, and Dominykas Jonas Blynas took over for less than a year. Blynas, a journalist and financier, focused his articles on economic and financial topics. However, he did not stay long as editor, returning to his publishing company, Pažanga. This led to two new editors taking over the position:

- Simas Aleksandravičius, responsible for the overall content of the newspaper, its supplements, and both editorial offices

- Ignas Šeinius, a writer and enthusiast of Scandinavian literature.

Šeinius, however, was replaced within a year due to his strong communist leanings, with Vytautas Alantas stepping in. These three editors were instrumental in introducing two editions of the newspaper in a single day. The paper was so popular that one edition would sell out within hours. Readers hoping to buy it after work were left empty-handed. In response to reader demand, the editorial office began publishing two editions daily from October 1935:

- Rytinis Lietuvos Aidas (Morning Echo of Lithuania) at 6:00 AM

- Vakarinis Lietuvos Aidas (Evening Echo of Lithuania) at 1:00 PM

The two editions not only differed in content, covering current events, but also underwent significant changes compared to earlier years. The newspaper expanded to 10–12 pages with five columns, added photographs, and altered fonts for the title and individual headlines. To the left of the title, within a frame resembling a coat of arms, was the motto: Tautiskoij, Mintis, Kelias, Ateitin (Nation, Thought, Path, Future), with the date of the first issue framed similarly on the right.

In the 1930s, the main themes included the rise of fascism and national issues close to Lithuanian hearts, as Bolshevik Russia pressed from one side and Poland from the other.

The Most Popular Daily in Lithuania

From 1935 onward, for the next four years, Alantas, known for his strong nationalist views, led the editorial office alone. His significant contribution to the newspaper`s history was preparing it for a third daily edition. However, he did not celebrate this milestone, as in April 1939, Aleksandras Merkelis, a literature researcher and journalist, took over as editor-in-chief.

On May 9, 1939, for the first time, three daily editions of Lietuvos Aidas were published in the Lithuanian market, making The Echo the most popular daily newspaper in Lithuania. Its editorial team grew to nearly 70 people, including many Kaunas-based journalists. The newspaper had a language section led by linguist Dr. Antanas Salys and a substantial network of correspondents, with French journalist Henry de Chambon standing out. By the late 1930s, its circulation reached 90,000 copies.

The year 1939 was challenging not only for the editorial team but also for Lithuania itself. Historian Liudas Truska described those days:

“From the mid-1930s, as the threat of war grew and the influence of Germany and the USSR increased in Europe, discussions began both at the ‘top,’ including the presidency, and among the ‘lower’ ranks about which country—Germany or the Soviet Union—should be approached in case of danger. President A. Smetona and most Lithuanian politicians leaned towards Russia, believing it posed less of a threat to Lithuanian national identity.” (Lithuania 1940-1990: A History of Occupied Lithuania. V., 2007, p. 137).

The Echo aligned itself with the ruling party and began criticizing the Lithuanian clergy, which adopted an anti-Russian, anti-Bolshevik, and anti-communist stance. Given the presence of many priests in the editorial team, tensions escalated.

The End of Independent Lithuania: The Second End of The Echo

On November 2, 1939, Merkelis stepped down from the newspaper, and at the start of the new year, journalist and lawyer Tomas Bronius Dirmeikis took over as editor-in-chief. To ease tensions, he invited economist and publicist Domas Cesevičius and Augustinas Gricius to act as editors-in-chief for the morning and evening editions, respectively.

After Germany and Russia invaded Poland, Vilnius and the Vilnius region were returned to Lithuania. However, both the government and the Echo editorial team remained in Kaunas. The joy was short-lived. In June 1940, the Red Army entered Lithuania. On June 15, Lietuvos Aidas announced the occupation of the country. The Lithuanian clergy had been right.

The following day, June 16, in the Sunday morning edition, The Echo published the Soviet ultimatum to the Lithuanian government, which was accepted. Independent Lithuania became history, and the newspaper`s journalists resigned.

Unwilling to run the editorial office under Soviet occupation, many employees left not only Kaunas but also Lithuania. It was evident that the Soviets would not allow the continuation of such a nationalistic and oppositional newspaper. For a brief moment, the newspaper was led by Jonas Šimkus, who made the final decision. On July 15, 1940, the last issue of Lietuvos Aidas, numbered 5544, was published.

Writer Jonas Miškinis summarized the years of The Echo as follows:

“The Lithuanian Echo fully justified its name, ‘The School of the Nation,’ in pre-war independent Lithuania. Through its compelling words, it educated thousands of patriotic Lithuanians who considered serving their nation the most important mission of their lives… It was the most popular newspaper in interwar Lithuania. Why? The ideas it published met the Nation’s expectations and aspirations, discussing Lithuania’s events in depth, unlike a sheet of paper blown away by the wind.” (Laisvas laikraštis, March 12–25, 2004, p. 20).

Thus ended the second chapter of Lithuania’s national newspaper.

Five Long Decades of Silence

After World War II, Lithuania became one of the Soviet republics, subjected to repression and deportations. Many journalists of Lietuvos Aidas, especially its last editors, were imprisoned, exiled to Siberia, or disappeared without a trace. Valentinas Gustainis and Domas Cesevičius returned from Siberia to Lithuania only in the mid-1950s. Ignas Šeinius emigrated to Sweden, where he gained citizenship, while Vytautas Alantas settled in the USA. Jonas Šimkus, the last editor-in-chief of Lietuvos Aidas, stayed in Kaunas and worked as an editor of Darbo Lietuva (Working Lithuania).

For the next five decades, Lietuvos Aidas remained only a memory for Lithuanians. However, as the Soviet Union began to crumble, Lithuania declared independence once again on March 11, 1990. Despite Russian tanks on the streets of Vilnius, the Republic of Lithuania was free.

Two months later, on May 8, Lietuvos Aidas—the Lithuanian Echo—was reborn in Vilnius, under the common slogan BLOKADINIU (Blockade), acknowledging the challenging days of the independence struggle.

Mirroring its design from 73 years prior, the title arched above the Vytis emblem within a circle. To the left of the coat of arms was the word VALSTYBES (States), and to the right, LAIKRAŠTIS (Newspaper), all underlined by a colorful stripe. The editorial article revisited the 1917 piece, whose words were remarkably fitting for the nation’s circumstances, beginning: Finally, the conditions in our country have changed enough to allow the publication of Lietuvos Aidas... Fully aware of the driving force and significance of this hour.

The Sentiment of the Elderly, the Curiosity of the Young

Alongside recollections, the newspaper included political updates in the Parlamento kronika (Parliament Chronicle), a report on the road to freedom by Vytautas Landsbergis, and topics of daily interest such as culture, sports, and regional news. Once again, The Echo became the organ of the Supreme Council of the Republic of Lithuania, earning its title as the "School of the Nation."

The first editor-in-chief of the freedom-era The Echo was Saulius Stoma, an architect and publicist. Stoma graduated from the Faculty of Architecture at the Vilnius Institute of Civil Engineering and began his career in that field while contributing to professional journals. When offered the role of editor-in-chief of The Echo, he accepted without hesitation, despite having recently become co-editor of another publication.

The Echo quickly regained its former glory, evoking nostalgia among older Lithuanians and attracting the interest of younger generations. Stoma assembled a team of professionals and established collaborations with prominent Lithuanian figures. By the end of the year, the newspaper’s circulation reached 51,000 copies.

During this time, the cultural weekly Šiaurės Atėnai (Northern Athens) was launched, co-founded by Stoma. The editorial office of The Echo, with its greater resources, supported smaller publications by printing them as supplements. Although Šiaurės Atėnai established its own association in 1990, by 1994, it functioned as a supplement to The Echo before becoming independent again.

Similarly, on February 9, 1991, Savanoris (Volunteer), a publication dedicated to the Volunteer National Defense Forces, was released. Savanoris remained a supplement to The Echo until April 24, 1994, after which it became an independent newspaper.

Stoma led the editorial office for four years. In January 1991, he introduced several changes to the newspaper’s design. The title was straightened, with a small Vytis placed above it, accompanied by the words States and Newspaper. The Echo was published five days a week, from Tuesday to Saturday, but occasionally released special editions for significant national or global events. This occurred on Monday, August 19, 1991, when the newspaper reported on the Moscow coup that had taken place the previous day.

Between 1990 and 1992, The Echo served as a government organ. At the end of 1992, the Lietuvos AIDS joint-stock company was established, and the newspaper was privatized, becoming an independent publication.

An Athlete at the Helm of The Echo

In 1993, the newspaper entered circulation with 103,000 copies but faced significant financial difficulties. Stoma, who left the editorial office in 1994, was accused three years later of embezzling funds from the newspaper and was sentenced to prison.

From 1994 to 1996, the editor-in-chief was writer and politician Saulius Šaltenis. In May, Šaltenis restored the traditional design of the main headline. The title returned to its arched form with a prominent Vytis emblem in a circle, though the side inscriptions were removed. It was clearly stated that the newspaper had been established in 1917, and navigation features were added.

In 1996, a new domestic supplement, Autobirža, a motoring magazine, delighted the male readership. The following year, readers received Kauno žinios (Kaunas News) and the weekend supplement Šeštadienis (Saturday). By then, a new editor-in-chief had taken the reins: Roma Grinbergienė-Griniūtė, a former handball player and sports journalist.

Grinbergienė, after retiring from sports, graduated in German philology and worked with newspapers Sport and Vytis. She joined The Echo team in 1993. During her tenure, Lietuvos Aidas changed its logo.

A New Coat of Arms, A New Logo

From its inception, The Echo used the Vytis as its symbol. In 1991, the government introduced a new, ornate coat of arms featuring a griffin, unicorn, crown, and the motto VIENYBĖ TEŽYDI (Let Unity Bloom). This decorative version of the Vytis replaced the knight on horseback in 1997.

That same year, the Saturday edition’s front page featured caricatures of notable figures, drawn by Lithuanian artist Miečislov Ščepavičiaus, alongside works by Joana Plikionytė and Paulas Beckmanas, who lived in the USA. The illustrated series ran until mid-1998, after which it was replaced by photographs.

Despite supplements, the introduction of colors, and public affection, Lietuvos Aidas faced financial troubles. Loans were insufficient to cover operational costs. Two consecutive editors-in-chief, Jonas Vailionis (1998) and Rimantas Varnauskas (1998–2000), were unable to resolve the situation. Circulation dropped to 7,000 copies. By December 1999, the company owed five million litas (the Lithuanian currency until January 1, 2015). Plans to declare bankruptcy and close the newspaper were underway. At that point, politician and publicist Algirdas Pilvelis stepped in.

Pilvelis, trained as a mining engineer and historian, was a passionate politician, journalist, and photographer. His photographs were widely used by Lithuanian newspapers, art galleries, and television, and remain influential to this day. In the late 1990s, Pilvelis entered politics, founding the Reformų Partija (Reform Party). In later years, he ran for the presidency.

At the age of 55, with extensive experience, Pilvelis took on the task of saving the Lithuanian School of the Nation. In May 2000, he officially became the owner of Lietuvos Aidas. However, the situation was dire, requiring drastic decisions.

What was once a daily newspaper began publishing only twice a week, on Wednesdays and Saturdays. Despite the challenges, the Kaunas office remained open, though collaboration with freelancers was reduced. Journalist Aurimas Drižius was elected as editor-in-chief by vote.

War with Authorities and a Complaint to the Pope

In July of the same year, Drižius published a series of articles exposing financial irregularities involving Vilnius officials, specifically Mayor Artūras Zuokas. The first article, titled The Mayor of Vilnius Already Owns a Large Plot Near Gediminas’ Castle, was published on July 19, and soon a flood of accusations followed. Offended, the mayor filed a complaint with the Inspector for Journalists’ Ethics and the Chairman of the Journalists’ and Publishers’ Ethics Commission. He also threatened to sue for defamation.

In the fall, another series of articles (50 in total) on anti-Semitic topics came to light. Both controversies took a toll on the newspaper and its editors. Although the paper faced no significant legal repercussions, Pilvelis apologized for the articles targeting Jewish Lithuanians. Still, readers turned their backs on the newspaper. Subscriptions were canceled, and circulation dropped dramatically, reaching only 5,000 copies by September 2002.

In February 2001, more troubles arose. The State Tax Inspectorate announced that Lietuvos Aidas owed 3.36 million litas in back taxes and froze all of its assets, including private ones. It was no secret that the then-government was no ally of the newspaper—in fact, quite the opposite. Thus, Pilvelis and Drižius declared war on the authorities.

On February 9, 2001, the online portal Delfi reported: A. Pilvelis and His Allies Defended the “Freedom of the Press”: “Dozens of readers and journalists from the daily Lietuvos Aidas protested in Vilnius against the government’s attempt to ‘suffocate the only Lithuanian newspaper telling the truth.’ The rally, organized by the director and owner of the newspaper, Algirdas Pilvelis, was supported by Monsignor Alfonsas Svarinskas and MP Stanislovas Buškevičius.”

Pilvelis announced his intention to file a complaint with Pope John Paul II and Brussels regarding the deliberate destruction of the newspaper. More protests and a hunger strike were declared. “There is no other option but to fight to the end,” Pilvelis said at a press conference. “The authorities will never take over Lietuvos Aidas. I will continue working even if only 3–5 staff members remain in the newsroom.”

And that’s what happened. In November 2001, Drižius left, followed by other journalists. Pilvelis himself took over as editor-in-chief, and The Echo began its fight for survival.

Before the Court: Two Echos at Once

Pilvelis believed in his newspaper. In 2000, he wrote: “Lietuvos Aidas is Lithuania’s first daily and the only one that dared to stand against the explosion of human anger channeled into wrongdoing—the daily bread of Lithuanian media. Without Lietuvos Aidas, there will be no Lithuania. Instead, there will be a vague territory inhabited by officials, judges, prosecutors, police officers, businessmen, criminals, and prostitutes proud of their depravity and ‘sexuality’—a territory of people without a homeland or memory, a spiritual wasteland. But not Lithuania.” (LA, October 24, p.2.)

The tireless editor, who was also active in Lithuanian politics, forged new connections and revived old ones. He relocated the newsroom to modest premises at Gediminas Avenue 2, attempting to sell the colossal former headquarters (1,770 m²) at Maironio 1, but to no avail. In 2014, the website Pamirsta.lt published an article about the abandoned, empty former editorial building.

For the next four years, The Echo continued to publish in a reduced format. It covered parliamentary sessions (Rolandas Paksas, Liudas Truska, and others), commented on national events (Alfons Svarinskas), reflected on the road to freedom (Alberts Griganavičius), and described cultural events (Jonas Rudziński). In 2005, a supplement titled Naujausios žinios (Latest News) was even released.

However, problems persisted, and 2006 brought an even greater crisis. On April 20, the Vilnius District Court received a bankruptcy application for the company. A month later, on May 2, the court decision took effect. With no other options, layoffs began. In December 2006, a group of journalists led by Antanas Ališauskas launched an alternative daily under the same name, referencing the history of The Echo since 1917. Following the debut of the new publication, Ališauskas stated:

“Pilvelis did not register the name ‘Lietuvos Aidas’ with the patent office, so he is not the true publisher of the newspaper. This created an opportunity to revive the ‘Echo of Lithuania’ that disappointed its nearly 100,000-strong audience. (…) And this year, after completing formalities with trademark registration offices, the first issue of the new Lietuvos Aidas appeared in the publishing market.”

The second Echo operated until 2012, when its publisher, ADENITA JSC, went bankrupt and shut down. Meanwhile, in June 2006, Pilvelis became a shareholder of ELTA, a news agency, and continued working. As he promised, he “would not give up, even if only five people remained in the newsroom.” Only three stayed.

The Foundation as The Echo’s Lifeline

Pilvelis owned a private printing house in Trakai, and since 2004, The Echo was printed there. He wrote poetry, haiku, took photographs, and edited individual issues himself. Step by step, he rebuilt the newsroom, regained readers’ trust, and wrote the next chapter in The Echo’s history. This was made possible thanks to good people, friends, and loyal readers. On May 10, 1999, the AIDAS foundation was established, helping the newspaper endure tough times.

By 2007, circulation had reached 15,000 copies. Despite challenges, controversies, and legal battles, Pilvelis persisted. He wrote articles for all sections, which ranged from politics, culture, religion, and sports to more modest but significant topics like transportation, travel, health, and charitable causes.

Key features included columns like In Memoriam, a tribute section, and Poezija, which featured poems reminiscing about the past and lamenting present losses. These attracted seasoned poets and young talents alike. Readers recognized Birutė Silevičienė as the author of the most beautiful poems about Lithuanian villages, their inhabitants, and their dreams. Over the years, she received various awards and contributed articles to The Echo.

Editor Pilvelis didn’t overlook the educational needs of his readers. He was supported by experts like Dr. Egidijus Staigys (LA, October 14, 2011, In Search of 21st Century Medicine) and Prof. Jonas Grigas (LA, November 12, 2013, Let’s Be Citizens of the Cosmos), who frequently shared their insights. Nature articles were penned by Dr. Eglė Gudeliūnienė, while Martynas Miškinis defended Vilnius’ Old Town.

A significant section was dedicated to European Union matters, featuring commentators like Gintvilė Switters and Irena Tumavičiūtė, alongside specialists such as Sociologist Dr. Vytautas Ramanauskas.

Editor Pilvelis’ pride was the Tautos Mokykla (School of the Nation) column. Articles here were patriotic and filled with love for Lithuania and its people. Academics, scientists, travelers, writers, and journalists all contributed. In 2009, Pilvelis launched a website: www.aidas.lt.

Tribute to Algirdas Pilvelis

In 2012, the anniversary of Lietuvos Aidas was celebrated with great ceremony. Although it was referred to as the “95th,” this was not entirely accurate. The newspaper was founded over nine decades ago but was technically younger. However, as Vytautas Žeimantas wrote, Lietuvos Aidas has walked a path marked by turmoil and violence, revival, and determination never to surrender.

In 2015, the company Lietuvos Aidas was officially dissolved, and the newspaper`s publication was taken over by a foundation of the same name. True to his role as owner and editor, Algirdas Pilvelis steered the ship, preventing it from sinking, until the end of his days. He passed away suddenly on August 27, 2016.

He left behind the Valstybės laikraštis “Lietuvos aidas”—the national newspaper Lithuanian Echo—in excellent condition. It was elegant, featuring high-quality photographs, a two-column format, 16 pages, and a team of 40 contributors. Among them were writers, scientists, and doctors from various specialties, supported by Cardinal Audrys Jouzas Bačkis, businessman Jonas Viesulas, and musician Stasys Juškus. All names were listed in the editorial footer.

The Echo was published twice a week, on Tuesdays and Saturdays, with triple numbering. After the editor’s death, there was a brief pause in publication.

On September 10, 2016, a Saturday issue dedicated to the late editor was released. Colleagues, collaborators, officials, and readers bid him farewell. The editorial team, apologizing for the interruption, reassured readers: “We will continue the editor-in-chief’s path, promoting Lithuanian identity and creativity. After all, Lietuvos Aidas laid the foundation for free Lithuanian journalism and is said to have significantly contributed to rebuilding our statehood. We are committed to ensuring that our newspaper continues to live and grow stronger.”

The declaration was signed on behalf of the editorial team by the new editor-in-chief, Rasa Čemeškienė, privately the daughter of the late editor.

One Hundred Years of Lietuvos Aidas!

The long-time owner did not live to see the newspaper’s centennial. The jubilee celebrations took place in Kaunas on September 6, 2017. To mark the occasion, the book by Ona Voverienė titled “Lithuanian Echo”—The School of the Nation was published. Drawing from articles written since 1994, the author discusses the newspaper`s history, editors, and journalists. “Because they shape the face and spirit of the newspaper,” she emphasizes, adding that “The Echo almost always promoted the highest standards of journalistic work and duty to the Homeland. It was a true school, guided by love for the homeland and justice. It safeguarded the Nation and the independent Lithuanian State, cultivated Lithuanian patriots, taught love for the Homeland, and instilled respect for state institutions, history, and culture.”

- Česlovas Iškauskas – always up to date with current events.

- Vilius Litvinavičius – ensuring the morality of the nation.

- Jonas Adolfas Patriubavičius – striking at the nation’s conscience.

- Lina Pečeliūnienė – strengthened the wings of Lietuvos Aidas.

- Antanas Rimantas Šakalys – bringing light to the darkness.

Although The Echo’s circulation dropped to 3,600 copies in 2017, Rasa Pilvelytė-Čemeškienė courageously upheld her father’s vision and implemented his ideas. She introduced color to the newspaper and launched new sections, such as Teisė ir teisingumo vykdymas (Law and Justice Administration), Mokslas ir IT (Science and Information Technology), and Interviu su įdomiu žmogumi (Interview with an Interesting Person), often contributing to the latter herself.

An Interesting Section: Gatvė (Street)

A notable section is Gatvė (Street), which addresses urban and rural street issues: bad weather, accidents, traffic radar systems, and congestion problems. History remains an important focus, both the country’s and individual stories, along with religion, entertainment, and culture. Sometimes, The Echo transforms into an art gallery, as on May 29, 2018, when issue 115-7 featured a collection of watercolors and drawings by Kazys Kęstutis Šiaulytius, a Lithuanian watercolorist, caricaturist, and educator.

With a smaller editorial team, articles from other sources, such as internet portals, are often published. For instance, in August 2020, an article by Ruta Blaustein defending the Jewish cemetery titled Leave the Graves of Our Great Vilnius Ancestors in Peace was featured, having first appeared on the Alkas.lt portal two weeks earlier.

Today, Lietuvos Aidas is more modest than during the interwar period or the 1990s but continues to exist. Although absent from social media, it maintains a website and, as stated by the editor, is available in print nationwide. The Friday edition is more comprehensive, richly illustrated, and updated—just as a weekend edition should be.

The Echo actively participates in local and national social and cultural events, such as the Christmas Goose Fair in Pagėgiai (an ethnographic region of Minor Lithuania) or initiatives to protect and preserve Lithuania’s oldest oak tree in Stelmužė.

Lietuvos Aidas has risen three times, as poet and essayist Sigitas Geda remarked: “We are a national and social newspaper. A symbol of memory and events. The word ‘Lietuvos’ obliges us to unite all who live here, regardless of origin and nationality, regardless of education, epaulets, or regalia.”

Timeline of Lietuvos Aidas:

- 1917, September 6 – the first issue of Lietuvos Aidas was published

- 1918, October 1 – Lietuvos Aidas began publishing six days a week

- 1918, February 19 – historic issue featuring the declaration of independence

- 1918, December 31 – the last issue of the daily in Vilnius

- 1928, February 1 – Lietuvos Aidas returned to the scene (Kaunas)

- 1929 – illustrated supplement Iliustruota apžvalga was introduced

- 1930 – introduction of color advertisements

- 1935, October – two daily editions of the newspaper began

- 1939, May 9 – three daily editions of the newspaper began

- 1940, July 15 – the last issue; Lietuvos Aidas fell silent for five decades

- 1990, May 8 – the third rebirth of Lietuvos Aidas

- 1991 – change of visual identity

- 1992, end of the year – the newspaper was privatized

- 1994, May – return to traditional visual identity

- 1997 – logo redesigned

- 1999, May – establishment of the AIDAS foundation

- 2000, May – Algirdas Pilvelis became the newspaper`s owner

- 2000, June – the newspaper began publishing twice a week

- 2001, February – all assets of the newspaper were frozen due to unpaid taxes

- 2001, February 9 – protest by journalists and readers in front of the parliament

- 2004 – printing moved to Trakai

- 2005 – introduction of the supplement Naujausios žinios (Latest News)

- 2006, May 2 – official bankruptcy of the company declared

- 2006, December – an alternative newspaper titled Lietuvos Aidas appeared on the market

- 2009 – launch of the website www.aidas.lt

- 2015 – liquidation of the company Lietuvos Aidas; publication taken over by the foundation

- 2016, August 20 – September 10 – publication paused due to the owner’s death

- 2017, September 6 – centennial celebration of the newspaper’s founding

- 2018 – introduction of color to the newspaper

Sources:

- http://antologija.lt/text/jonas-basanavicius-mano-gyvenimo-kronika/25

- https://proxy.europeana.eu/media/2021803/C1B0003957107/eb212e777b28843834b3edaaa67b1bbd?disposition=inline&recordApiUrl=https%3A%2F%2Fapi.europeana.eu%2Frecord

- http://sena.mab.lt/lt/archyvas/2412/1878

- https://lt.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lietuvos_aidas

- https://www.aidas.lt/lt/apie-mus

- https://web1.mab.lt/2018-01/lietuvos-aidas/

- http://lzs.lt/lt/naujienos/zurnalistikos_istorija/pirmasis_lietuvos_aido_istorijos_tarpsnis_1917-1919_metai.html

- https://pries100metu.kaunomuziejus.lt/irasai/1918-m-liepos-13-d-liudas-noreika-valstybinis-susipratimas/

- https://www.vle.lt/straipsnis/lietuvos-aidas/

- https://przegladbaltycki.pl/11074,maj-1939-litewski-naczelny-wodz-w-warszawie.html/lietuvos-aidas-rastikis

- https://www.reklamos-archyvai.lt/leidinys/lietuvos-aidas/1900-2000

- http://sena.mab.lt/lt/archyvas/2412/1878

- https://www.santaka.info/?sidx=28749

- https://www.aidas.lt/lt/lietuvos-aido-simtmeciui/article/15964-02-11-lietuvos-aido-100-metu-sukakciai-antanas-smetona-lietuvos-aido-dvasios-formuotojas

- https://www.wiki-data.lt-lt.nina.az/Lietuvos_aidas.html

- https://www.lrytas.lt/lietuvosdiena/nelaimes/2016/08/29/news/mire-zinomas-leidejas-algirdas-pilvelis-1155937

- https://pamirsta.lt/lietuvos-aido-bustine

- https://stirna.info/media/aidas-lt/2009

- https://kestutis-galerija.blogspot.com/2018/05/

COMMERCIAL BREAK

See articles on a similar topic:

Le Nouvelliste. History of Haiti's Oldest Daily Newspaper

Małgorzata Dwornik

Surviving its first year only due to a wine and potato importer, it held a monopoly on news from France. It meticulously avoided blending news with commentary - until the U.S. occupation of Haiti in 1915. It was elevated to the top by a trio known as the “Holy Monsters.” Thus begins the story of the Haitian daily, Le Nouvelliste.

History of Television in Australia. It All Began with a Studio in a Windmill

Małgorzata Dwornik

Already in 1885, thanks to Telephane, an invention by Henry Sutton, it was possible to watch horse races for the Melbourne Cup. The first real television broadcasts, conducted from 1934 at the old windmill on Wickham Terrace in Brisbane, were watched by only 18 television owners, but by the following year, test transmissions had begun in other major cities.

Weekly News Of The World: History of Success and Downfall

Małgorzata Dwornik

The publication appeared on the market in 1843 and quickly gained popularity. In the 1930s, Winston Churchill contributed to its pages. Two decades later, it set a world record with 8.6 million copies, thriving on sensationalism and scandal. Crossing boundaries ultimately sealed the fate of News of The World. It disappeared in 2011 due to a massive phone-hacking scandal.

The History of Press Photography

Bartłomiej Dwornik

The birth of photography is dated to 1839, when French painter Louis Daguerre announced the principles of daguerreotype (an image projected through a lens onto a silver-plated copper sheet, developed with mercury vapor, and fixed with sodium thiosulfate).

The History of Title Case. Where Did Capitalized Titles Come From?

Krzysztof Fiedorek

Title Case, a style where most words in titles begin with a capital letter, has shaped the look of English publications for centuries. Its roots trace back to the 18th century when the rise of the printing press influenced how information was presented.

Słowo Polskie. A Polish Daily with Over a Century of Tradition

Cezary Kaszewski

"Słowo Polskie" began its life in Lwów, with the first issue published on Christmas Eve, 1895. The newspaper quickly gained readership. By 1902, its circulation exceeded 10,000, and three years later, it reached 20,000, making it the first high-circulation daily in Galicia.

The Fourth Estate in America: I Write, Therefore I Am...

Urszula Sienkiewicz

The press in the United States, extensively discussed before, has another intriguing niche that cannot be overlooked when talking about American media. Magazines: weekly and monthly publications for enthusiasts.