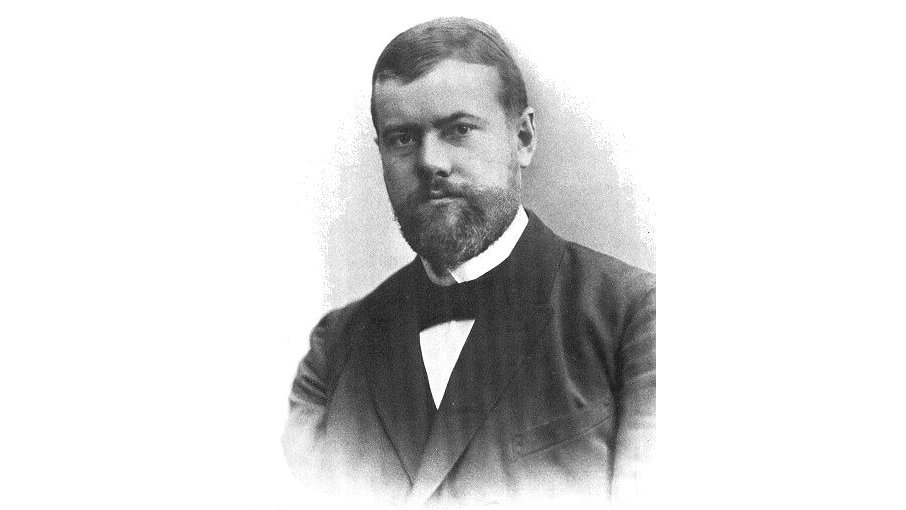

Max Weber in 1894 [photo US Public Domain/Wikimedia]

Max Weber in 1894 [photo US Public Domain/Wikimedia]As Władysław Markiewicz wrote in his book "Society and Sociology in the Federal Republic of Germany" - ...."he constructed a theoretical system, although in many significant respects not fully refined, but surpassing significantly all that has been created in Germany in the field of social sciences since the times of Marx due to its broad horizons, originality of approaches, versatility of analysis, and above all, rigorous precision in thinking and reasoning." One can say that Max Weber`s role transcends German science, and his influence on global sociology - especially American sociology - is widely recognized.

His theory of the sociology of political relations largely remains unfinished, as he did not realize his intended comprehensive work dedicated to the sociology of the state. His contributions to the sociology of political relations are scattered throughout various works, among which the posthumously published "Economy and Society", released in 1922, holds particular significance from the perspective of this discipline. Sociological analyses are also contained in Weber`s political writings.

The starting point of Weber`s sociology of political relations is the search for the reasons why modern European societies differ from others known from history or occurring in other parts of the world. This very issue inspired Weber when he worked on the theory of the sociology of religion and largely influenced his development of the theory of the sociology of power.

There is another similarity between Weber`s sociology of political relations and the entirety of his sociological views. In the sociology of power, as with other sociological issues, he seeks to delineate, as well as understand the interrelationships between three fundamental spheres of social life: the sphere of power, the sphere of economy, and the sphere of values. For the sociology of political relations, Weber`s analysis of the relationship between power and its legitimacy holds fundamental importance. This is where Weber`s essential contribution to the sociology of political relations lies.

However, when discussing this contribution, one must be aware that Weber`s position did not constitute such a fundamental opposition to Marxism as he believed. It is a significant merit of Weber that he systematically analyzed the issues of values in the sphere of politics and integrated them into his theoretical system of the sociology of political relations. This is a lasting contribution to science, which does not logically contradict the Marxist analysis of political life.

The central concept of Weber`s sociology of political relations is "domination" [Herrschaft], which he distinguishes from power in a more general sense that arises from economic strength; an example Weber gives is the power of a large bank over those seeking loans when the bank holds a nearly monopolistic position in the market. Here we have power, but not domination in Weber`s sense of these terms. Domination implies the capacity to issue commands, not just, as in the case of economic power, a fundamental advantage that can be leveraged to impose one`s will.

Domination is thus a relationship between the ruler and the ruled, in which the former is capable of imposing their will through binding orders. Such domination, Weber argued, cannot merely be the result of possessing force. Although he did not deny the role of violence as a basis for relations of domination, he correctly emphasized that mere violence is insufficient for a system of domination to arise and function effectively in a sustainable manner. It is necessary to have specific values and beliefs upon which the obedience of the ruled to the rulers is based.

Here - in the analysis of types of legitimacy of domination - lies Weber`s fundamental contribution to the sociology of political relations. In analyzing this issue, Weber constructed three "pure types" - in his understanding, ideal types: these are "traditional domination", "charismatic domination", and "legal domination".

The first two were necessary for Weber to illustrate the fundamental difference of the type of domination he associated with modern European societies - namely, legal domination. The analysis of the latter and the paths of its emergence is also Weber`s contribution to the theory of political development or - to use the terminology often employed in contemporary non-Marxist sociology of political relations - the theory of political modernization.

Traditional domination is based on the subjects` belief that the power is legitimate because it has always existed. Rulers have rights in relation to the ruled and hold a position of masters over their servants. However, their power is limited by sanctified norms of tradition, on which their very domination also rests. In this sense - Weber states - "a ruler who would violate tradition without constraints and limitations would thereby jeopardize the legitimacy of his own power, which rests solely on the force of tradition."

Weber`s analysis of traditional domination contains a number of interesting typologies and historical findings. Among them, particularly noteworthy is the interpretation of the mechanism of power that exists under traditional domination. This apparatus initially functions as an extended "house" of the ruler, in which individual servants are responsible for various spheres of life. This expanded "house" of the ruler, Weber calls "patrimonialism"; he also provides a good example of such a system in the form of ancient Egypt.

In addition to the analysis of patrimonialism, Weber also constructed a second type of traditional domination, which he called "sultanism"; its characteristic feature would be the ruler`s liberation from traditional constraints, thus complete, unrestricted despotism. Sultanism becomes possible when the traditional ruler expands the scope of their power through conquests and can ultimately base it much more on the coerced obedience of subjects than on their belief in the legitimacy of traditional power. However, this requires an effective army. Weber provides an interesting analysis of five types of military organization that underpin sultanism, including:

- an army composed of slaves, subjects, colonists, etc., to whom the ruler assigns land and tools in exchange for specific services, including military service;

- an army made up of slaves designated solely for military service;

- mercenary armies;

- an army composed of individuals who receive land solely in exchange for the obligation of military service;

- an army recruited from subjects, usually commanded by members of privileged classes.

In analyzing the forms and ways of functioning of these military organizations, Weber emphasized the paradox of despotic systems. This paradox lies in the fact that by relying on the military, they become increasingly dependent on it, which leads to the weakening of their power. Finally, departing from the pure type of traditional domination, Weber tracked its concrete, thus not pure, mixed incarnations. He analyzed the relationship between patrimonialism and feudalism, presenting the latter as a different variant of traditional domination, rich in various variations.

In a similar, typological manner, Weber approached another type of domination -

Charismatic domination. The Greek term charisma signifies for Weber an extraordinary quality, a gift possessed by individuals or objects; others believe that charisma confers magical powers on those who possess it. A charismatic leader is someone whose domination over others is based on their belief in his extraordinary, magical abilities. The charismatic leader has a special mission assigned to him and has the right to obedience from the subjects in its name. As in traditional domination, power is based on the characteristics of the ruler, not on impersonal laws. However, unlike traditional domination, it is not the result of something that has always been, but the result of the conviction that the charismatic leader brings new content. Weber emphasized that this is a revolutionary leader [in the sense that he changes the established state of affairs], a providential man rescuing from crisis, a prophet in a religious or quasi-religious sense.

The fundamental problem of charismatic domination is, as Weber asserted, the problem of succession, which essentially does not exist in traditional domination, unless the principles of legitimate inheritance of the crown are not sufficiently clear and precise, or someone claims the throne, contesting another successor`s rights [for example, questioning their lineage, claiming precedence, etc.]. By its very nature, charisma is a characteristic of an individual and cannot be easily transferred like a traditional title to power. Weber distinguishes three methods of transferring power in the system of charismatic domination.

In the first case, there are specific criteria that the successor must meet to become the new charismatic leader. In the second case, the previous charismatic leader designates his successor, thereby transferring his own charisma to him. In the third - most common, as the first two are rather exceptional - the most important disciples or followers of the charismatic leader appoint his successor, who thus becomes the bearer of charisma.

The inheritance of power in the Catholic Church occurs precisely on this basis, although this power also invokes legitimacy in the form of the appointment of the first successor of Christ - by the apostle Peter - by the founder of the religion himself. However, subsequent popes come from a choice made by authorized disciples, but at the moment of election, the charisma of Christ magically descends upon them. By analyzing the Church`s example, Weber created an interesting sociological analysis of the structure and functioning of this institution, in which he saw the fullest example of the institutionalization of charisma.

Both traditional domination and charismatic domination were primarily needed by Weber as reference points in his analysis of the third type of domination - legal domination - in which he saw the political peculiarity of the West. This particular analysis is the most important part of Weber`s sociology of political relations and also - though this does not belong to the topic - Weber`s sociology of law.

Legal domination is the domination of law in the sense that both the very existence of power and its scope depend on positive laws established by humans. This principle of legal rationality lies at the foundation of the systems that Weber collectively referred to as "legal domination." Weber`s concept of legal domination looks as follows:

- in this domination, every norm can be enacted as law, and it is expected to be respected by those who are subject to power;

- the law constitutes a set of abstract rules, and its dimension lies in applying abstract rules to specific cases;

- those occupying positions of power are not personal rulers but superiors fulfilling duties defined by law at a strictly defined time;

- the ruled are free citizens obliged to obey the law, not subjects obliged to obey the ruler who applies the law.

Weber claimed that such a system represents the peculiarity of the Western world and one of the two fundamental causes - alongside religion - for the high level of development and modernity that this world has achieved.

In analyzing the system of legal domination, Weber devoted much attention to the apparatus of power of such a state, namely bureaucracy. He was convinced that bureaucracy represents the most rational form of exercising power, although at the same time he saw and emphasized its shortcomings and weaknesses, for example, when it comes to making decisions in individual, atypical cases. Bureaucracy, as a system of exercising power, is characterized - according to Weber - by the following properties:

- official matters are handled continuously;

- they are handled according to a set of established norms and rules that define the duties of each official associated with their position, the scope of their power, and the means of coercion at their disposal;

- the power and responsibility of each official are merely parts of the entire hierarchy of power and are derivative of this hierarchy. An official possesses power not by virtue of their individual qualities but by virtue of the position they occupy in the hierarchy of power;

- the means used to exercise power are the property of the organization, not the private property of individual officials; the latter have the obligation to account for the manner in which they utilize the means that they have due to their exercise of power;

- positions and offices do not constitute private property of those who occupy them, hence they cannot be sold, given away, or inherited;

- the entire process of the functioning of the bureaucratic organization is based on the circulation of documents.

Referring to this ideal type of rational bureaucratic organization, Weber also created the type of bureaucratic official within the system of legal domination. This is:

- a personally free individual appointed to their position on the basis of a contract;

- an individual exercising power based on impersonal rules, whose loyalty pertains to faithfully performing official duties;

- an individual appointed to the position based on qualifications;

- an individual employed wholly, not partially, in the position they occupy;

- an official who is regularly paid, with career prospects guaranteed by impersonal laws.

Weber`s attitude towards bureaucracy, whose analysis constitutes one of his significant contributions to sociology, was rather complex. Three layers can be distinguished in this attitude:

- the analysis of bureaucracy as a technically efficient instrument of exercising power;

- the critique of bureaucracy in relation to its natural tendency - to which Weber claimed - of exceeding its proper functions;

- an interesting analysis of bureaucracy as a reflection of class structure.

While in "Economy and Society," Weber focused on the first aspect of this issue, in his political writings, he discussed the second and third more extensively. Only by considering them together can one obtain a complete picture of Weber`s theory of bureaucracy.

The major lines of Weber`s sociological and political reflections allow us to fully recognize him as the most important theorist of non-Marxist sociology of political relations.

In analyzing his work, many commentators point out that from the perspective of theoretical content and empirical findings, there is no fundamental contradiction between Weber and Marx. The main difference lies in the fact that Weber undertook his analysis from distinctly bourgeois positions, siding with the capitalist system, which he saw as the embodiment of rationality, and in favor of the bourgeoisie as a class. Today`s commentators on Weber`s views clearly highlight this aspect of his views. However, in Weber`s case, we have an interesting example of a great scholar with a profound understanding of political phenomena who was able to contribute to sociology not due to, but despite his clearly defined bourgeois theoretical position.

This, however, is a problem not only for Weber - one characteristic of great theories in the non-Marxist, bourgeois strand of sociology of political relations - and sociology as a whole - is that despite the limitations imposed by the class and ideological position of the researcher, they were capable of posing significant problems and introducing momentous solutions. Although many of them require critical analysis, the scientific greatness of these theories lies in the fact that they are not merely testimonies to the failures of human thought, but are links in the process of scientific knowledge.

Source: Lectures of the Master`s Part-time Journalism Program at the University of Warsaw.

COMMERCIAL BREAK

New articles in section Skills and knowledge

War reporter in the new reality. Evolving techniques, same purpose

KFi

What happens when war breaks out just across the border and journalists aren't ready? Polish reporters faced that question after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022. Lacking training, they improvised: blurred details, hid names, and balanced trauma with truth.

A heuristic trap in media coverage. How loud headlines boost fear

Bartłomiej Dwornik

A negative message that rests on emotion lifts the sense of threat by 57%. Why do reports of a plane crash drive investors away from airline shares? Why do flood stories spark worry about the next deluge? The pattern is irrational yet clear and proven.

How LLMs are reshaping SEO. Smart content strategies for the age of AI

BDw

For years, SEO was a fairly predictable game. Pick the right keywords, optimize your content, and watch your website climb the rankings. But today, a silent revolution is underway - and it`s being led by large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, and DeepSeek.

See articles on a similar topic:

How Information is Created?

Agnieszka Osińska

The media construct the world for us - the audience. However, most viewers, listeners, or readers do not have direct access to the issues discussed in the reports.

Max Weber's Theory of Political Sociology

Krzysztof Dowgird

Max Weber, a German sociologist who lived from 1864 to 1920, was undoubtedly the greatest non-Marxist sociologist of political relations. He had a tremendous and enduring impact on many branches of social sciences, including the sociology of political relations.

Writing for the Web. The 4x4 Rule for Content Optimization

Bartłomiej Dwornik

How do you craft a Google-friendly title, what’s the ideal article length, and how often should you use keywords? A guide for those writing for websites.

Chronemics, or The Language of Time. What Your Watch Says About You

Bartłomiej Dwornik

You walk in on time, glance at your watch, wait five minutes, then leave. Someone else is thirty minutes late and acts like they had to wait for you. Time in communication is a tool, a weapon, and a status marker. Welcome to the world of chronemics. The study of how time affects human relationships.