source: kazpravda.kz

source: kazpravda.kzAfter the fall of the Tsarist regime in Russia, the young socialist government allowed the creation of autonomous territories for national minorities. Thus, before the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics was officially established in December 1922, the Kyrgyz Autonomous Socialist Soviet Republic was founded a year and a half earlier in August 1920. This was proudly reported by the young newspaper, just seven months old, published in Russian: Известия Киргизского Края (News from the Kyrgyz Region).

The title, based in Orenburg, was a weekly and was issued on Thursdays. Its first issue hit the stands on January 1, 1920. The editor-in-chief, Valery Lezhava-Murat, explained the purpose of the new media outlet in his first editorial, which filled the entire front page: to establish law and order among the region`s population and government agents responsible for guiding the lives and activities of the people, and to gradually create a printed organ that would not only be official but also reflect the needs and requests of the vast Kyrgyz region, thus establishing a people`s newspaper.

In the second issue, he appealed to anyone with surplus paper to deliver it to the Printing Department of the Regional Economic Council. This request was prompted by a shortage of the material, which led to News being printed in broadsheet format with eight pages. However, the aspirations of the editorial team extended beyond this.

The need of the hour. Reprinting radio broadcasts

Soon, News became the media arm not only of the republic`s government but of the entire country. In addition to regional updates, the newspaper featured proclamations and resolutions from the highest authorities. Journalists had to be very cautious with their language and expressions, as the Workers` and Peasants` Councils, led by Lenin, declared war on the Russian intelligentsia, and education was not favorably viewed. Consequently, articles often consisted of reprints and concise descriptions of events.

Despite these constraints, a popular section of the weekly, starting from the second issue on January 8, was Из последних радио (From the Latest Radio). Written records of radio broadcasts from the front or events outside Kazakhstan brought much news and novelty, especially since radio was a luxury far beyond the reach of the proletariat in Russia and Kazakhstan, far from Moscow or Petrograd.

A year into its existence, there were slight changes in the newspaper`s life. The editorial team was taken over by Dmitry Naronovich, followed by Alexander Marin, and the weekly was renamed Степной правдой (Steppe Truth). At that time, more attention was given to regional economic issues, and the newspaper introduced a new section, Народное хозяйство (National Economy), covering agriculture and industry both locally and nationally. The newspaper became an organ of the RCP (Russian Communist Party) and the Central Executive Committee of the republic. The formation of the USSR and the proceedings of the First Congress became the year`s priority topics.

However, shortcomings in Kazakh journalism led to staffing shortages, inadequate political training, and poor communication with the public, which often struggled to understand the authorities` decisions. This resulted in yet another change in the editorial team, less than a year after the first.

The Soviet Steppe. A new name, a new style

In November 1923, two newspapers, Степной правдой (Steppe Truth) and Оренбургский рабочий (Orenburg Worker), were merged. Under the keen supervision of editor Peter Kusmartsev, the former weekly became a daily newspaper, adopting the name Советская степь (Soviet Steppe). The paper retained this name until January 20, 1932, and during this time, its editors-in-chief included:

- 1923-1925 Lev Heifetz

- 1925 Nikolai Feoktistov

- 1926 Nikolai Turikov

- 1926-1928 Alexander Schwer

- 1928 Mykola Pishchalnikov

- 1929 Nikolai Martynenko

- 1929 Pavel Rysakov

- 1929 Sadyk Safarbekov

- 1929-1930 Boris Krasny

- 1930 Nikolai Sedov

- 1930-1932 Pyotr Varlamov

The newspaper also changed its style, embracing true journalism. While it relied on well-known Russian names like Olga Forsh, Konstantin Simonov, Alexei Tolstoy, Sergei Mikhalkov, and Konstantin Paustovsky, local Kazakh journalists and writers began honing their craft. Essays, articles, and opinion pieces appeared in the Steppe, which often criticized flaws such as sloppiness, bureaucracy, and parasitism.

In August 1929, the newspaper was recognized as the official organ of the Kazakh Regional Committee of the All-Union Communist Party of Bolsheviks, the Central Executive Committee of Kazakhstan, the Alma-Ata District Party Committee, and the Regional Executive Committee. Its editorial office was moved to the new capital of the republic, Almaty, and Boris Krasny was appointed as editor-in-chief.

Political humor and sneaking in information

Soviet Steppe was now a thoroughly modern newspaper, featuring photos, graphics, and even political humor - though within the bounds of contemporary "decency and approval". It had seven columns, headlines in different fonts separating the texts, six pages, and a proper newspaper format. In addition to its main political and informational sections, the paper included regional and thematic sections:

- Agriculture

- Food Front

- Professional Life

- Life of the RCP

- Union Life

- Through Villages and Settlements

There were also cultural, tourism, legal, and economic sections. Of course, it published government announcements and decrees. Editors-in-chief were usually party officials, tasked with ensuring that texts adhered to ideological and party lines. Some, like Alexander Marin and Alexander Schwer, had journalism training, which improved the paper`s presentation.

$1 trillion of global advertising market value 👇

Despite party discipline, loyalty to ideals, strict censorship, and the "sword above their heads", journalists occasionally sneaked important information into their writings. For instance, during the 1930-1933 Soviet-induced famine in Kazakhstan, hints and leaks about the tragedy appeared between the lines. Such acts carried severe penalties, so most staff refrained from taking such risks.

Among the notable journalists of this era were poet and writer Olga Bergholtz, Pavel Kuznetsov, and correspondents Pavel Rogozinsky and Sergey Krushinsky.

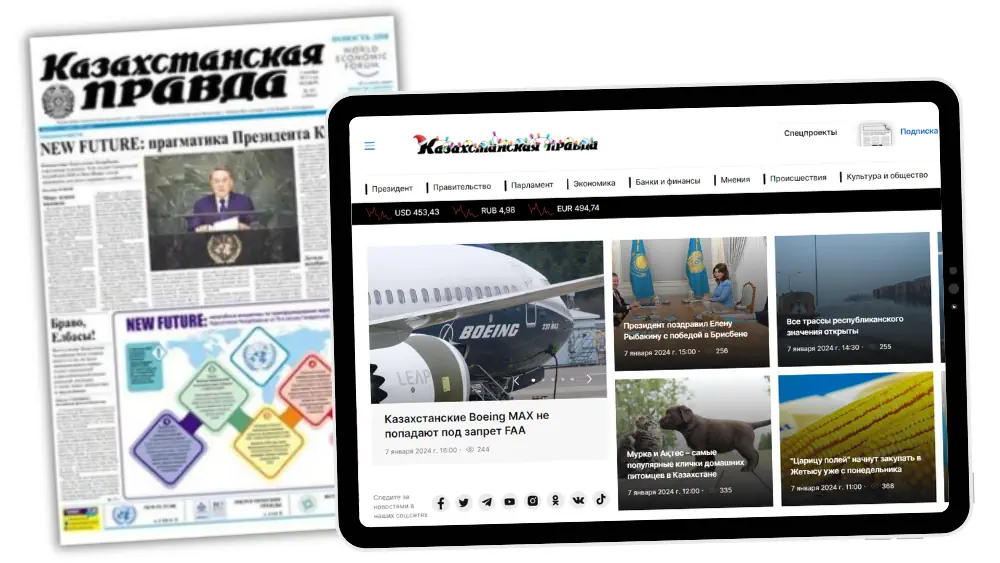

Kazakhstanskaya Pravda. Correspondents go into the field

The newspaper`s situation changed in 1932, under the leadership of Arkady Savin. On January 20, the III Plenum of the Kazakh Regional Committee renamed the paper to Казахстанская правда (Kazakhstanskaya Pravda). The first issue under the new title was published the very next day, January 21. The editorial board received permission to send its own correspondents to various regions of the country, with collectivization and industrialization being the main topics.

In 1933, the editorial board was headed by Ivan Gubanov, the first editor-in-chief with journalism training. Although he initially graduated from the Omsk Party School, he later completed the All-Union Communist Institute of Journalism in 1930 at the age of 24. He had worked for Komsomolskaya Pravda and was sent to Kazakhstan in 1932, where he also led literary newspapers. Unfortunately, he fell out of favor with the authorities in 1937, succumbing to repression and dying in 1938 at the young age of 32.

Until the outbreak of the Great Patriotic War in 1941, Pravda met expectations. It competed with the newspaper Социалистик Казахстан (Socialist Kazakhstan) and often outperformed it. Pravda was considered more "cultured and worldly" than its competitor, though ideology always took precedence. Despite frequent changes in editors, the paper maintained good condition. During the 1930s, its editors-in-chief included:

- 1932-1933 Arkady Savin

- 1933 Ivan Gubanov

- 1933-1937 Nikolai Verkhovsky

- 1937 Nikolai Gusev

- 1937-1938 Daniil Terentiev

- 1938-1940 Alexander Shumakov

- 1940 Sergey Kostyukhin

When the Kazakh ASSR gained the status of the Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic and became a direct member of the USSR in 1936, Pravda was led by Nikolai Verkhovsky, a graduate of a parish school and workers` faculty. His newspaper career began at the age of 19. Before arriving in Kazakhstan in 1933, he had worked for newspapers in Chelyabinsk, Perm, and Sverdlovsk. Like many of his contemporaries, he faced repression in 1937 but returned to the party and its newspapers a year later. He was the first editor-in-chief of Pravda to hold the position for more than a year, serving for four years.

War, exile, propaganda. Plus poetry and literature

In 1940, a year before the war with Germany broke out, the editorial office was taken over by Konstantin Nefedov. After completing a journalism course, he worked at newspapers in Stalingrad and Saratov. In January 1937, he was arrested but rehabilitated three months later. He was tasked with leading Pravda during the Great Patriotic War and its aftermath (until 1948). He returned to the role of editor-in-chief in 1955.

The 1930s and 1940s were marked by gulags, labor camps, and exiles for Kazakhstan. These lands became a destination for convicts, unwanted compatriots of other nationalities, and ordinary criminals. At the same time, industrial development and natural resource exploitation were prioritized. During World War II, Kazakhstan became a stronghold for the arms industry, and this dominated the front pages of Kazakhstanskaya Pravda. Coverage also honored the country`s defenders and soldiers, as well as the brave youth who dug trenches and shelters, as reported on New Year`s Eve 1941. Sadly, many of these young people lost their lives in a failed propaganda-driven initiative to develop the virgin lands (celinnyje).

Relationship and tech. Study about love in the age of likes 👇

For the next four years, the newspaper focused on the war, victories, party work, and the cult of "Father Stalin". Many Kazakhs fought on the front lines, and the local press remembered them. However, cultural and spiritual matters were not neglected. Kazpravda, as the paper became known, stood out among the few functioning publications in Kazakhstan at the time by including poetry, essays, and excerpts from books. Most of these works were imbued with patriotism and propaganda, with the sole aim of achieving the "victory of the Soviet people".

On June 23, 1941, a special issue was published containing the mobilization decree. Many such issues followed, but the one on May 9, 1945, was especially joyful for readers.

Journalists on the front lines. Pen and rifle

Many journalists fought on the front lines of World War II, some with only a pen and others with a rifle. The Kazakh units were no exception. From Kazpravda, eight journalists went to the front: Yevgeny Bard, Anatoly Vlasenko, Boris Linov, Boris Megorsky, Ivan Konstantinovich, Arseny Petrashko, Ivan Yuferev, Vasily Yakushkin.

Only limited records remain about Petrashko and Yakushkin. Petrashko joined Kazakhstanskaya Pravda as a reporter in 1936. He was the first among his Kazakh colleagues to enlist in the army, joining Panfilov`s Guards Division. He died in 1942 during the Battle of Ignatkovo near Moscow.

Yakushkin became a correspondent for the newspaper in 1937, invited while still a student at the Communist Institute of Journalism in Almaty. He reported from western and northern Kazakhstan before heading to the front in July 1941. He died in January 1942 near the village of Krasnaya Polyana.

In honor of these fallen journalist colleagues, a memorial plaque was unveiled on the editorial office wall during the 70th anniversary of victory in the Great Patriotic War. Earlier, in January 1970, for the newspaper`s 50th anniversary, a special issue was dedicated to them.

Another significant name from this era is Dmitry Salanov. An alpinist and photographer, his images of Kazakhstan`s natural beauty graced the pages of Kazpravda. His notable photojournalism includes a report on the August 18, 1936, ascent of the "Spirit Ruler" peak in the Tien Shan mountains by athletes from Almaty. Salanov headed to the front on July 14, 1941, and died two years later.

Post-war truth in Pravda

After the war, Kazpravda remained the official organ of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan and the Supreme Council of the Kazakh SSR, as stated in the headlines on the front page. The slogan was the same as everywhere: Proletarians of all countries, unite!

The newspaper had four pages, six columns, and continued to be written in Russian. Patriotic spirit, love for the motherland, and reverence for national leaders permeated every section. Kazakh writers such as Abu Sarsabayev, Gaziza Abishev, Malik Gubdulin, and Sanigal Seyitov rose to prominence.

In 1948, the editorial office was led by Ignat Nikitin, who ran it for seven years and became known for his "ideological disputes". He was sent to Kazakhstan in 1939 and brought experience from leading a factory newspaper. After a brief stint in regional newspapers, he became deputy editor-in-chief at Kazpravda. In 1955, he was reassigned to Yaroslavl.

The post-war period was challenging, marked by Stalin`s regime of repression, arrests, and exiles. Words had to be chosen carefully. Although far from Moscow, politics deeply influenced daily life in Kazakhstan. Key positions, both in government and significant institutions, were held by "faithful ideologues" with the proper education and family background. Kazakhstanskaya Pravda was no exception; its editors-in-chief were expected to demonstrate unwavering party loyalty. Over the following decades, the newspaper had seven main editors:

- Konstantin Nefedov, 1955-1957

- Fyodor Boyarsky, 1957-1963

- Andrey Kiyanitsa, 1963-1965

- Fyodor Mikhailov, 1965-1979

- Ivan Spivakov, 1979-1982

- Albert Ustinov, 1982-1986

- Fyodor Ignatov, 1986-1991

All editors were party members and held significant roles within it. Unlike their pre-war predecessors, they had journalism education and practical experience. All had worked for various newspapers, and some had also worked in radio. Ivan Spivakov was the first editor educated in Kazakhstan, graduating from Kazakh State University. The standout record-holder was Fyodor Mikhailov, who led the paper for nearly 15 years.

The thaw of the 1950s. Kazakhstan didn`t love Stalin

The 1950s in Pravda were marked by articles about rebuilding the country, five-year plans, and the development of collective farms and agriculture, but also... a slight thaw. In 1953, Stalin died, and Kazpravda informed its readers in a special issue on March 6. Although the "only correct political direction" still applied, the country felt a reduction in pressure and terror. It became evident that Kazakhstan had never loved the leader.

The newspaper, still the government’s mouthpiece, changed its approach to readers. It became more friendly and "local". Although government decrees and resolutions were still printed, there was a significant increase in regional information. Ignat Nikitin focused on the culture and economy of the region. Stories of ordinary people (a tram depot worker, a miner) began to appear.

In 1955, the newspaper celebrated its 35th anniversary, and by the end of the decade, the large slogans about the committee and the party on the front page had been shortened to a single sentence: Organ of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan, the Supreme Soviet, and the Council of Ministers of the Kazakh SSR. The proletarian slogan, of course, remained. On the left side of the title, the republic`s emblem appeared.

The next decade brought news about space exploration and the Cold War, but what truly excited the Soviet people and was eagerly awaited all year was January 1 - New Year’s Day and everything that revolved around it. It may seem strange, but the tradition of celebrating this holiday was and still is deeply ingrained in the Russian people and former republics. War and revolutionary anniversaries? Important, but more for the state. New Year’s Day was for ordinary people. Kazakhstan Pravda had a special approach to this day because "New Year is always a celebration, a belief in magic and Father Frost (perhaps more than Santa Claus), the wonderful smell of the Christmas tree, and the hope for happy changes".

New Year traditions

New traditions were born: January 1 was declared a public holiday, with the snowflake (a girl in a white starched dress) as its symbol, and new toys like round clocks appeared. But Kazakhstan Pravda also had its own New Year’s traditions. The first issue of the year included:

- addresses from government members (since the war)

- a recipe for Olivier salad (with a new ingredient each year)

- New Year recipes for special dishes contributed by the female editorial staff

- New Year’s tales

- in the 1970s, graphics began to feature a different color each year

Among the newspaper`s traditions (not only for New Year`s) was political humor. A leading figure in this field was Vladimir Nesterov. Although not a full-time employee, he was associated with Kazpravda for nearly four decades. His collaboration with the newspaper began in the 1930s. After the war, he published "cartoons exposing the Cold War, militarism, racism, Zionism, and more. His deep professionalism, vast erudition, and ability to understand the political situation of the time were reflected in cartoons executed with great graphic skill and humor".

In the early 1950s, the artist traveled through northern Kazakhstan, resulting in posters, portraits of leaders and workers, as well as postcards and children`s books. Most of these works were showcased at an exhibition organized for the 35th anniversary of Kazakhstan Pravda in 1955. The artist passed away in 1988.

Another "funny employee" of the era was Vyacheslav Kamorsky, a veteran photojournalist. His first article appeared in Pravda in 1961. Kamorsky wrote, took photographs, and joked, especially on April 1. His humorous photos, such as one featuring a meter-long flower or a car in a tree, often fooled not only gullible readers but also his colleagues in the newsroom.

Editor-in-chief Fyodor Boyarsky and the entire Kazpravda team celebrated the publication of the newspaper’s 10,000th issue on March 23, 1958. On this occasion, the newspaper was awarded the Order of the Red Banner of Labor by decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.

The new face of Kazakhstan Pravda. Sharp, fierce, and witty

The late 1960s and 1970s are known in Soviet history as the era of stagnation. The same direction prevailed: the party and the Central Committee as the sole legitimate authority, working for the great nation. Nothing new. However, individual republics began to feel the absence of their own identity. Despite being an "organ", Kazakhstan Pravda started to change its image, largely thanks to editor-in-chief Fyodor Mikhailov.

Mikhail Nikiforovich, a journalist at Kazpravda from 1970 to 1975, recalled his boss: "A man who loved the newspaper and knew how to see it through the eyes of an executive secretary. He did everything to make every issue work".

Mikhailov allowed articles about corruption, bribery, the difficult situation in villages, and bureaucratic excesses. Not only did he not avoid them, but he demanded them. His collaboration with Nikiforovich brought tangible results. His articles, The Chilly Incident and The Forbidden Nightingale, about reports from an ordinary hunter on high-ranking officials and their actions, were reprinted in newspapers across the USSR. The KGB`s efforts were in vain; the country learned about what was happening in the Kazakh forests (and beyond), and Kazpravda’s prestige and authority grew.

Mikhailov didn’t stop at politics. He also emphasized humor, satire, and essays, ultimately combining them all. He created an excellent team led by Gennady Rabotnev. Among the columnists were Kazakh authors such as Konstantin Selinovich, Nikolai Shevtsov, Eduard Medvedkin, Grigory Breigin, Vadim Karak, Yuri Tarasov, and Vyacheslav Kovalev. As Grigory Dildyaev, the youngest editorial staff member in 1970 (a student at the time) and editor-in-chief from 1994 to 1997, recalled: "Sharp, fierce, yet funny publications adorned the newspaper. An incisive headline and a fresh topic were valued, not just dry facts from the People’s Control Commission or police reports".

In 1975, Kazpravda celebrated its 55th anniversary with dignity. It had only four pages but eight columns. Alongside the main news sections, it featured an entertainment section with a crossword puzzle, a literary corner, numerous professional photos, and a good dose of humor.

Independent Kazakhstan and a new Pravda

Mikhailov left the editorial office in 1979, leaving it in the hands of Ivan Spivakov. However, significant changes in the newspaper occurred under the leadership of the next editor, Albert Ustinov (1982-1986). The year 1985 brought a sweeping change to the entire country. Mikhail Gorbachev introduced perestroika. The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) lost its power, new parties and freedom movements began to emerge, and censorship faded as freedom of speech gained momentum. This new direction in the media was not an easy transition, culminating in demonstrations and violent incidents in December 1986.

Ustinov, a party official, left for Moscow, and his position was taken over by Fyodor Ignatov, an Honored Journalist of Kazakhstan and the author of many books. Although fresh winds of change were blowing, Pravda still carried slogans about the proletariat and identified itself as a party organ, with the USSR emblem next to its title. This only changed in December 1991, when Kazakhstan declared its independence, transforming the image of Pravda and many other newspapers.

On December 17, 1991, Kazpravda, like all Kazakh newspapers, featured the news of Kazakhstan’s declaration of independence the previous day on its front page. Along with the country’s transformation, Kazakhstan Pravda also changed.

Despite earlier reforms across the USSR, the newspaper struggled with economic problems. Commercialization and privatization were rampant. The newspaper theoretically didn’t publish advertisements, and its "sponsor" was on shaky ground. The situation was saved by the first editor of the freedom era, Vyacheslav Srybnykh.

Srybnykh was sent to Kazakhstan and Kazpravda as punishment. He had been an instructor in the agitation and propaganda department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Kazakhstan and had "crossed the wrong person". He arrived at the editorial office of the renowned newspaper with no great career prospects. But history can be ironic.

The lone editor who achieved the impossible

In 1989-1990, a major conflict erupted at the top of the editorial office. Fyodor Ignatov’s deputy couldn’t reconcile with him and resigned, and a week later, Ignatov himself and several of his allies were dismissed. Only Srybnykh remained, and since the newspaper had to continue publishing, all responsibilities fell on him. Surprisingly, the former propaganda instructor managed well, despite having no secretary or contact with the central authorities.

At that time, there were two types of communication with the "important ones". One was a secure, tap-proof telephone with the USSR emblem, and the other was a regular service with central exchanges and special numeric codes. The latter was available in the editor-in-chief’s office, but Srybnykh only had a standard phone line, like everyone else in the city and country. For several days, phones rang in the empty editorial offices, but no one answered. The newspaper kept coming out while the office was empty? - President Nazarbayev was astonished - who is running this? "Srybnykh", came the answer. Soon after, the instructor was appointed as the newspaper`s editor-in-chief. Journalists were alarmed, but… it turned out that Srybnykh not only excelled in his new role but introduced a series of changes that saved the newspaper.

- He introduced a market-oriented work system.

- He launched an advertising section.

- He ensured articles were published only after being verified by at least two identical sources.

- He allowed and even encouraged critical commentary.

- He prioritized truth, openness, and honesty.

- He redesigned the front page.

Freedom, in every sense of the word, breathed through the newspaper. It became a publication that openly criticized both local and national authorities. No topics were off-limits. Corruption, bureaucracy, and the world`s troubles found their place in the new Kazpravda. The paper gradually increased its size as more topics emerged. Symbols of the past disappeared from the front page. Beneath the main title, the phrase: A Republican and Nationwide Political Newspaper appeared, followed by: Published since January 1, 1920.

The new Pravda captured readers` hearts. And poked at authority

Pravda became the most widely read newspaper, not because it was expected, but because people wanted and needed it. Its circulation soared. On November 11, 1993, the front page featured a photo of Kazpravda journalists with President Nursultan Nazarbayev. The headline read: We are with the President. And he is with us. And he recognizes our right to doubt, criticize, and suggest.

In the following months, Kazpravda openly addressed not only the problems of its readers and the country but also its own challenges. In February 1993, colleagues from the radio and television company targeted the newspaper, accusing it of being anti-Kazakh. On March 4, 1994, Srybnykh published an article titled Pressures from the Side, where he discussed attacks on the newspaper - not from above but from so-called national patriots.

The culmination of these attacks came in 1994 when Kazakhstan’s government decided to "silence" both the media and its "rebellious parliament". In early May, then-Prime Minister Akezhan Kazhegeldin personally visited the Kazpravda editorial office and dismissed Editor-in-Chief Vyacheslav Srybnykh. Just as in 1991, the editorial office was in turmoil, but this time for a different reason. Over his years as editor, Srybnykh had earned the respect of the newspaper`s staff and collaborators. He proved to be an excellent manager and leader, was well-liked, and his actions were appreciated. On Wednesday, May 18, 1994, another photo with the President was published. This time the headline read: We want to live and work in a state of law, and in the lower right corner, a note stated:

The media reported the imminent removal of the editor of the newspaper "Kazakhstan Pravda". In response to calls from readers, the newspaper`s editorial board deemed it necessary to clarify the situation. The newspaper’s editor received an invitation from the President to work in his press service. A meeting of the editorial staff was held, expressing the unanimous opinion that changing the newspaper`s editor at this stage is inappropriate and would cause great harm. This opinion will be conveyed to President N. Nazarbayev as one of the newspaper’s founders - the editorial team.

President Nazarbayev remained silent, and two days later, on May 20, the editorial footer listed Grigory Dildyaev as the editor-in-chief. In protest, several prominent journalists left the editorial office alongside their leader. A nationwide scandal erupted... such events in free Kazakhstan? But was it truly free?

"A journalist cannot love power". Until they do

Dildyaev knew *Pravda* well, having worked there for 15 years. Alongside Yuri Kukushkin and Victor Ageyev, he formed a cohesive news team responsible for the newspaper’s fourth page. After a stint in Moscow, he returned at President Nazarbayev’s request to lead the editorial team. He remained in charge for three years, during which thematic sections were introduced:

- Patron, a section on legal advice for everyone

- Juma-Friday, a column for Muslim readers

- Newspaper within a Newspaper, a section for women

- Salon, featuring meetings with fascinating people

A new column for journalists, titled How to Save State-Owned Press?, also appeared. This section tackled a growing challenge: the rise of the internet, increasingly aggressive television competition, and a crisis in print media as circulations plummeted.

Like his predecessor, Dildyaev resisted external pressures. He often reminded his journalists: Your job is to write. My job is to be responsible for the newspaper and everything published in it! The team quickly embraced their new leader, respecting him as both an editor and a mentor.

In an interview with *Central Asia Monitor*, Dildyaev remarked: A journalist cannot love power. The warmest feeling they can have for it is respect - and only if the authorities prove they deserve it. And they can only earn respect in the reader’s eyes when the journalist exposes their flaws.

Dildyaev did just that, which led to his departure. His successor was Valery Mikhailov, son of a former editor-in-chief, Fyodor Mikhailov, and author of the famous documentary *"The Great Hunger" (Chronicles of the Great Famine)*, which chronicled the Kazakh famine of 1931-1933. Despite the country’s challenges, Mikhailov worked tirelessly to maintain the newspaper’s prominence in the media landscape.

Relocation to Astana and farewell to objectivity

On October 16, 1998, by decree No. 1050 of the Government of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the state enterprise *Kazakhstan Pravda* was transformed into a joint-stock company named Republican Newspaper Kazakhstan Pravda. Its first president was Anatoly Gursky. A year later, the publishing house relocated to the new capital, Astana. The editorial team, consisting of 20 people, began operations in a building on Victory Avenue equipped with new computers.

That same year, the newspaper launched its website, www.kazpravda.kz. With the dawn of the new millennium, the site expanded to include English content, and the newspaper celebrated its 80th anniversary. The editorial team shifted its focus to analytical materials and expert commentary, with increasing use of color. The issue on June 9, 1998, was adorned in blue, commemorating Astana’s first day as the nation’s capital.

60% of digital creators do not verify information before publishing 👇

After the move, Mikhailov expanded the printing of government decrees and regulations, which won the favor of the "eternal president", Nazarbayev. While the government maintained strong ties with Russia, the newspaper’s title still featured the USSR emblem. Journalist A. Suleimanova of *VISION* remarked: To "save face", the paper’s policies had to part with objectivity. The newspaper occupies a specific niche and significantly influences public opinion. But does it tell the truth? It might be said that the newspaper does not deliberately hide the truth but simply does not tell it. Perhaps we should rename it "Another Truth"?

A competent and visionary editor-in-chief

Valery Mikhailov left the editorial office in April 2003, and his position was taken over by the first female editor-in-chief, Tatyana Kostina. She steered the newspaper until August 2017.

Before joining *Kazakhstan Pravda* in 1990, Kostina had already spent nearly 12 years in the media industry. At *Pravda*, she became head of the information service. After leaving in 1994, she returned as the first deputy editor-in-chief in 2002. A year later, in April 2003, she became the lead editor.

Her tenure marked a pivotal period for the newspaper, guided by her motto: Fast, competent, and reliable. She resisted external pressures, earning the respect and admiration of her colleagues as a competent leader. She invested in youth, actively participating in organizing the first *Days of Kazakhstan Pravda* at the Kazakh National University in March 2009. Despite the journalism faculty’s 20-year history, this event revived traditions connecting seasoned and aspiring journalists. A statement on the university’s website announced: This historic moment was sealed with a Memorandum of Cooperation signed by KazNU Rector, Academician B.T. Zhumagulov, and A.Yu. Tarakov, President of JSC ‘RG Kazakhstan Pravda’.

The agreement ensured student involvement in creating a Youth Page for the newspaper, internships for top students at the editorial office, and joint field trips with professional journalists.

During the celebration, the editorial team conducted workshops, courses on writing columns, a photography exhibit by Yuri Becker, and a forum titled The National-Republican Newspaper "Kazakhstan Pravda" in Kazakhstan’s Information Space, attended by journalists, students, educators, UNESCO, and UN representatives. On that day, *Kazakhstan Pravda* received the national journalism award Altan Samruk.

A year later, the newspaper launched its digital archive, and in 2013, it implemented the AxioCat system, Kazakhstan’s first electronic document management tool, enabling real-time newspaper production oversight.

Kazpravda correspondents are stationed worldwide, but the highlight of 2014 was their expedition to Antarctica, where they installed the newspaper’s flag. Under Kostina’s leadership, *Kazakhstan Pravda* demonstrated that it could deliver engaging, professional journalism, increase its circulation (110,000 copies), and appeal to a broad audience ranging from retirees and homemakers to politicians and diplomats.

Media makeover of the "Old Lady"

In 2015, the 95th anniversary of the newspaper was celebrated with great fanfare. There were awards, flowers, and memories of past years. Some suggested it was time to give the old lady a facelift as she had grown a bit rigid, and a year later, the old-new Kazakhstanskaya Pravda in a new format landed in the readers’ hands. The creator and implementer of the project was the deputy editor-in-chief, Sergei Nesterenko. The new design included:

- The newspaper title presented in a single line

- Links to the main articles in the issue above the title

- Sections: Read in the Issue and Read on the Website

- Change of main font to New Veljovic DS Pro Book

- A rubricator and heading system

- Enhanced visual content: extensive use of caricatures, collages, and infographics

- More analytical and timely content

- Introduction of QR codes

The revamped newspaper was published in November 2016. For the first time, it was fully in color. Next to the title, the emblem of Kazakhstan was displayed, with the text Daily, National Newspaper above it. The 25th anniversary of Kazakhstan’s independence was also highlighted with a dedicated graphic. On this silver jubilee, the newspaper launched several projects:

- A full-length section titled Chronicle of Independence

- A photography contest titled My Kazakhstan

- Industry Leaders, featuring stories about workers

The online portal was also modernized. Video materials were introduced as a novelty. The redesign of the newspaper was one of Tatiana Kostina`s last contributions before she retired in August 2017, leaving Kazpravda refreshed, modern, and global. She passed away from cancer in 2022. The leadership was taken over by Asyl Sagimbekov.

A Newspaper with a flag in Antarctica and its own mountain

Sagimbekov had not worked at Pravda before; he was the deputy editor of Evening Almaty. Taking over the country’s most-read newspaper was no small challenge. The publishing house also had a new president, Vyacheslav Pashchenko. Both men were tasked with ensuring that Pravda is read by those who shape the country’s economy and politics, as stated by Dauren Abayev, the Minister of Information and Communications. They rose to the challenge.

In mid-2018, the front page underwent minor changes, featuring only the title, the country’s emblem, and two navigation elements without images. The page became more streamlined. A column titled Svet Pobedy (Light of Victory) was introduced, along with a Friday section titled Nasha Kukhniya (Our Kitchen), which discusses Kazakhstan`s national dishes.

In October 2019, the project Rukhani Zhangyru (Spiritual Revival) was launched. Kazpravda, the State Archives of Astana, and local schools collaborated on a project allowing young people to touch history and conduct research on the city’s history and the people who left a notable mark on its chronicles.

That same year, the main topic was the renaming of the capital from Astana to Nur-Sultan in honor of outgoing President Nursultan Nazarbayev. Three years later, in 2022, the name Astana was reinstated, a name the city held until 1998 when it was known as Akmola.

The year 2020 was marked by the COVID-19 pandemic. The editorial team supported its readers, offering advice and assistance. But this year also marked the 100th anniversary of the newspaper. To honor this milestone, numerous retrospectives of earlier and recent times were published. There were exhibitions and ceremonies, awards, congratulatory letters, and flowers, though the pandemic restricted grander celebrations. On June 26, the newspaper received the President’s Award for significant contributions to the development of national media.

The same year brought another change in the newspaper`s history. On November 7, the Government of Kazakhstan adopted a resolution titled "On Certain Issues of State Property", which stated that JSC "Republican Newspaper Egemen Kazakhstan" would merge with JSC "Republican Newspaper Kazakhstanskaya Pravda". The official merger of the newspapers took place in March 2021.

Asyl Sagimbekov continues to lead Kazakhstanskaya Pravda, one of the few newspapers in Kazakhstan that reaches even the smallest villages and towns. Its print edition, online version, and presence on social media platforms are widely read. According to 2020 data, the most subscribers were found on:

- Instagram - 67.1k followers

- Twitter - 16.8k followers

- Odnoklassniki - 7.3k followers

- Facebook - 6.029k followers

- Vkontakte - 1,097 followers

The newspaper not only left its mark on Antarctica but also has a mountain named after it in the Turkestan region, as well as streets in Pavlodar and Petropavlovsk. It has 17 branches across the country. It is present in the lives of Kazakhstan and its capital and, above all, in the lives of ordinary people.

Timeline of Kazakhstanskaya Pravda:

- 1920, January 1 - The first issue of News of the Kirghiz Region

- 1921 - News is renamed Steppe Truth

- 1923, November - Steppe Truth merges with Orenburg Worker and becomes a daily titled Soviet Steppe

- 1929, August - The editorial office moves to Almaty and is recognized as an official government publication

- 1932, January 20 - Soviet Steppe is renamed Kazakhstanskaya Pravda

- 1932, January 21 - The first issue of Kazakhstanskaya Pravda

- 1941-1945 - Topics related to the Great Patriotic War, decrees, manifestos, and proclamations

- 1948-1955 - The period of so-called ideological disputes

- 1958 - The first design changes of the newspaper

- 1958, March 23 - The 10,000th issue of the newspaper and the awarding of the Order of the Red Banner of Labor

- 1965-1979 - The era of satire and humor, especially in the column section

- 1975 - The 55th anniversary of the newspaper

- 1985 - Perestroika, partial abolition of censorship, freedom of speech

- 1991, December - Kazakhstan declares independence, and the newspaper`s image changes

- 1993, November 11 - A historic photo with the country`s president

- 1998, October 16 - Kazakhstanskaya Pravda is transformed into the Joint Stock Company Republican Newspaper Kazakhstanskaya Pravda

- 1999 - The editorial office relocates to the country`s new capital, Astana

- 1999 - The newspaper`s website goes live

- 2000 - The English version of the website is launched

- 2009, March - The first Days of Kazakhstanskaya Pravda at the Kazakh National University

- 2009, March - The newspaper receives the "Altan Samruk" award

- 2010 - The digital archive of the newspaper is launched

- 2013 - The AxioCat system is implemented

- 2014 - The newspaper’s flag flies in Antarctica

- 2016, November - A complete redesign of the newspaper, which is published in full color

- 2019, October - The "Spiritual Revival" project

- 2020 - The newspaper’s 100th anniversary

- 2020, June 26 - The newspaper receives the president’s award for contributions to the development of national media

- 2021, March - The merger of Kazakhstanskaya Pravda with Egemen Kazakhstan

Sources:

- https://kazpravda.kz/n/istoriya-na-hrupkih-stranitsah/

- https://centrasia.org/newsA.php?st=1422611700

- https://kazpravda.kz/n/istoriya-na-hrupkih-stranitsah/

- https://e-history.kz/ru/calendar/show/27298

- https://www.booksite.ru/fulltext/1/001/008/057/593.htm

- https://web.archive.org/web/20170402163041/http://www.kazpravda.kz/page/view/o-gazete/

- https://ru.wikipedia.org/wiki/Казахстанская_правда

- https://kazpravda.kz/n/preodolevaya-vremya/

- https://tengrinews.kz/kazakhstan_news/novyiy-god-v-kazahstane-polveka-nazad-kak-eto-byilo-360245/

- https://kazpravda.kz/n/ushel-na-front-iz-nashey-gazety/

- https://vernoye-almaty.kz/studies/merzbacher1.shtml

- https://ourrocks.kz/index.php?title=Саланов

- https://clib.yar.ru/wp-content/uploads/2005/08/2005-08-12.pdf

- https://kazpravda.kz/n/o-chem-pisala-kazpravda-v-raznye-gody-v-kanun-novogo-goda/

- https://tramvaiiskusstv.ru/plakat/spisok-khudozhnikov/item/4645-nesterov-vladimir-vasilevich-1908-1988.html

- https://www.azattyq.org/a/kazakhstan_april_fools_day/26931490.html

- https://kazpravda.kz/n/moskovskiy-gorets-rodom-iz-kazahstanskoy-pravdy/

- https://www.caravan.kz/news/kak-byvshijj-instruktor-ck-kompartii-nauchil-redakciyu-plyuralizmu-846588/

- https://rus.azattyq.org/a/kazakhstanskaya-pravda-vyacheslav-srybnykh-1994-god/28128008.html

- https://vlast.kz/obsshestvo/veter_dekabrja_zagolovki_kazahstanskih_gazet_v_1991_godu-8801.html

- https://kzaif.kz/society/gazeta_imya_sushchestvitelnoe

- https://dknews.kz/ru/chitayte-v-nomere/252097-navsegda-glavred-kotorogo-est-za-chto-uvazhat

- https://online.zakon.kz/Document/?doc_id=30446416&pos=1;-16#pos=1;-16

- https://yvision.kz/post/quot-kazahstanskaya-pravda-quot-nedogovarivaet-ili-otkrovenno-vret-240007

- https://dknews.kz/ru/chitayte-v-nomere/257376-vsyu-zhizn-posvyatila-zhurnalistike

- https://kazpravda.kz/n/gazeta-primeryaet-novye-aksessuary/

- https://www.gosarhiv.kz/2019/10/16/5539/

- https://www.zakon.kz/redaktsiia-zakonkz/5047481-gazety-egemen-aza-stan-i-kazahstanskaya.html

- https://kazpravda.kz/n/vekovoy-yubiley-istoriya-stanovleniya-gazety-kazahstanskaya-pravda/

COMMERCIAL BREAK

New articles in section History of the media

Dimmalætting. History of the oldest daily in the Faroe Islands

Małgorzata Dwornik

The oldest newspaper in the Faroe Islands survived fires, bankruptcies, and the British friendly occupation. Although its end was declared many times, Dimmalætting has reported on archipelago life for 148 years. This title became a symbol of the struggle for identity for the Faroese people.

Jamal Khashoggi. A media trap, illusion of freedom, and price of free speech

Małgorzata Dwornik

He knew Osama bin Laden personally and advised Saudi kings, only to eventually become their greatest critic. Jamal Khashoggi entered the consulate in Istanbul and vanished without a trace, shocking world public opinion. This is the story of a man who traveled the path from palace salons to exile, paying the ultimate price for the fight for freedom of speech.

The History of The New York Times. All the news that's fit to print

Małgorzata Dwornik

In the heart of 19th-century New York, when news from across the world traveled via telegraph and the newspaper was the voice of public opinion, two ambitious journalists created a modest four-page daily that would eventually become a legend.

See articles on a similar topic:

Dorothy Day story. Journalist, feminist and saint candidate

Małgorzata Dwornik

She fought poverty with fire, defied war with silence, and prayed with clenched fists. Dorothy Day, once a communist and always a fighter, now walks the path to sainthood. Her journey from rebellion to devotion still divides and inspires. This is the story of "the rebel saint".

History of Folha de São Paulo. Brazilian Newspaper with a Guinness Record

Małgorzata Dwornik

The first issue was published on February 19, 1921, and the editorial team... quickly found itself at odds with Brazilian censorship. It was neither the first nor the last time. Over the years, the newspaper has faced countless clashes with the government, the military, and insurgent groups. The editorial team has suffered repression and acts of violence. However, its readers have always stood firmly by its side.

History of MTV. A Music Channel Where Music Once Disappeared

Małgorzata Dwornik

On August 1, 1981, at exactly 12:01 p.m. Eastern Time (USA and Canada), a new cable television channel launched: Music Television. John Lack welcomed MTV’s first viewers with the words: Ladies and gentlemen, rock and roll! The first music video aired was "Video Killed the Radio Star" by The Buggles.

POLITIKA. The history of Serbia's oldest daily newspaper

Małgorzata Dwornik

In 1904, journalist Wladislaw F. Ribnikar founded Serbia's first independent newspaper. Opponents predicted a quick failure for Politika, the government viewed it with suspicion, but readers... were captivated by its new quality. Ribnikar laid the foundations for modern Serbian journalism, but his successors faced mixed fortunes.