In April 2016, Cardinal Timothy Dolan, Archbishop of New York, did something that turned heads in both religious and secular circles. He opened the canonization process for Dorothy Day-a woman who had once been a communist, a radical feminist, and a fierce critic of capitalism. This move raised eyebrows. How could someone who once marched with anarchists and challenged both Church and State be considered for sainthood? But Day’s life defied easy labels.

She was a walking paradox: a devout Catholic who never stopped fighting for social justice, a pacifist who refused to pay war taxes, and a mother who gave up love for the sake of faith. Her journey drew attention from three popes-John Paul II called her a "servant of God", Benedict XVI cited her as a model of conversion, and Pope Francis praised her as one of four great Americans alongside Lincoln, Martin Luther King Jr., and Thomas Merton. Dorothy Day’s story isn`t about finding comfort in belief. It’s about waging battle with conscience, walking a tightrope between protest and prayer, and choosing service over safety.

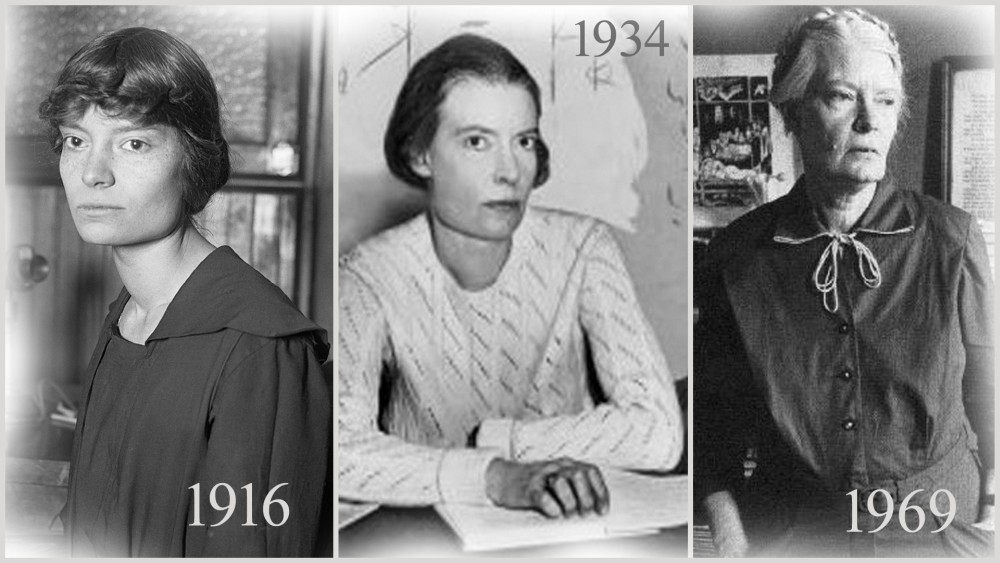

fot. corbisimages/Public Domain/Wikimedia, New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection/Public Domain/Wikimedia i Roscoe x/Public Domain/Wikipedia

fot. corbisimages/Public Domain/Wikimedia, New York World-Telegram & Sun Collection/Public Domain/Wikimedia i Roscoe x/Public Domain/WikipediaRestless youth and the call of socialism

Dorothy Day was born in Brooklyn Heights on November 8, 1897, into a Protestant family of modest means. Her father, John, worked as a sports journalist, and her mother, Grace, kept the household in order. When an earthquake in 1906 destroyed her father’s newspaper in Oakland, California, the family was forced to move again-this time to Chicago. Dorothy was already one of five children, and the financial pressure fell heavily on her parents.

As a child, she had a fiery temper and often tested boundaries. She once stole money from her mother just to see how far she could go. Her father, emotionally distant, left parenting to his wife. Yet something unexpected happened. Despite her family’s lack of religious practice, Dorothy became curious about God. At age ten, she began reading the Bible, driven not by faith but by rebellion. She joined a local Episcopal church, sang in the choir, and studied liturgy and catechism with almost obsessive dedication. It was the beginning of a lifelong tug-of-war between faith and resistance.

As a teenager in Chicago, Dorothy buried herself in books. She consumed Dickens, Dostoevsky, and Upton Sinclair with a hunger that bordered on obsession. These authors didn’t just entertain her-they fueled her sense of injustice. But she didn’t want to read about poverty from a distance. She wanted to feel it. To understand the pain of the poor, she experimented on herself. She lived in unheated rooms, skipped meals, and learned how little a person needs to survive.

Her empathy wasn’t theoretical-it was physical. In 1914, at age 18, she joined the Socialist Party and enrolled at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. She was drawn to the Russian thinkers-Tolstoy’s spirituality, Gorky’s fire, Dostoevsky’s darkness. These voices shaped her early worldview. She believed society needed more than charity. It needed revolution. She gave away the money her parents sent her, lived frugally, and shopped only at second-hand stores. But college felt too slow. In 1916, restless and eager to act, she dropped out and returned to New York, where history was waiting.

Journalism, lovers and bitter freedom

In New York, Dorothy threw herself into the boiling pot of radical politics and journalism. She started writing for leftist magazines like The Masses and The Liberator, where her sharp pen and strong opinions quickly made her stand out. She covered strikes, unemployment, and the struggles of working-class women. Her articles were passionate, informed, and deeply personal. She also wrote for The Call, a daily paper sympathetic to the Russian Revolution. One of her first major assignments was interviewing Leon Trotsky. Her life at this time blurred the line between reporting and activism. She wasn’t just writing about change-she was demanding it.

Her personal life mirrored the chaos of her politics. She smoked, drank, and fell in love with the wrong men. She formed friendships with communist icons like Elizabeth Gurley Flynn and Anne Louise Strong. She had affairs with literary figures, including Eugene O’Neill and Mike Gold. In 1917, when the U.S. entered World War I, Dorothy joined the Silent Sentinels protest in front of the White House, demanding the right to vote. She was arrested, sentenced to 30 days, and led a hunger strike in jail. After her release, she worked in a hospital, where she met Lionel Moise-a relationship that would leave a permanent scar.

She became pregnant, but Moise convinced her to have an abortion. He told her that motherhood was a trap and love was incompatible with social activism. She gave in. After the procedure, he vanished, telling her she lacked vision and should just "marry rich". The betrayal broke her. Years later, she wrote about it with brutal honesty: "I thought I was free and modern. I wasn’t. Freedom was a costume I wore to win a man who never saw me."

In 1921, trying to escape her pain, she married Berkeley Tobey, a wealthy publisher, and sailed to Europe. The marriage lasted a year. By 1924, she published her first memoir, The Eleventh Virgin, a raw and revealing account of love and loss. With the royalties, she bought a small house on Staten Island and began writing again-this time for Catholic magazines. From 1925 to 1929, she lived with Foster Batterham, a biologist and anarchist, and again found herself caught between love and belief.

A daughter, a crossroad and conversion

In 1926, Dorothy gave birth to a daughter, Tamar Teresa. The pregnancy shocked her. She had believed that the abortion years earlier had left her sterile. Holding her newborn child changed everything. Her faith, once a curiosity, now became urgent. She began attending Mass, reading Catholic texts, and speaking with nuns-especially Sister Aloysia, who became her spiritual guide. But this awakening shattered her relationship with Batterham. He hated organized religion and refused to marry or baptize their child. Dorothy faced a hard choice. She could follow him or follow her faith. This time, she chose God.

In July 1927, Tamar was baptized. That December, Dorothy entered the Catholic Church. Friends called her a traitor. Her family was baffled. Leftist circles rejected her. But she didn’t flinch. She believed in the Church’s teachings-not just on paper, but as a path to serve the poor. By 1929, she ended things with Batterham, though they remained in contact for their daughter’s sake. Dorothy returned to New York and worked various jobs, including writing garden columns and book reviews. After the 1929 stock market crash, she briefly worked in Los Angeles as a screenwriter. But her heart remained with the poor. In December 1932, covering a hunger strike for Commonweal, she wept and prayed. She asked for a way to serve both God and justice. The answer came soon.

The Catholic Worker is born

In 1933, Dorothy met Peter Maurin, a French immigrant with wild ideas and deep faith. He had no degree, no steady job, but his vision of Catholic social justice aligned perfectly with hers. Together, they launched The Catholic Worker, a newspaper aimed at workers, the poor, and anyone left behind by the Great Depression. The first issue, published on May 1, 1933, had a print run of 2,500 copies. It sold for a penny. Within three years, circulation hit 150,000. The paper carried no ads. Contributors worked for free. Day served as editor from 1933 until her death in 1980.

Unlike other Catholic media, The Catholic Worker embraced radical ideas. It promoted nonviolence, voluntary poverty, and solidarity with the oppressed. Dorothy wrote about labor strikes, tenant evictions, papal encyclicals, and the Sermon on the Mount. She criticized both capitalism and communism, insisting that the Gospel offered a third way. Readers didn’t just get opinions-they got action plans. She demanded readers not only pray, but feed, shelter, and stand with the poor.

Hospitality, not ideology

Soon, the newspaper became a movement. The Catholic Worker communities opened Houses of Hospitality across the country. These were not shelters. They were homes-places where guests and volunteers lived side by side, sharing meals, prayers, and struggles. The first house, located in Dorothy’s apartment on East 15th Street, served 400 meals a day by 1937. Others followed in Chicago, Los Angeles, and London. The movement grew without a central office or formal hierarchy. It was held together by love and letters.

Dorothy lived what she preached. She gave away her belongings. She once handed a poor woman a diamond ring someone had donated, saying: "God made diamonds for the poor too." She rejected state welfare and criticized the rise of consumer culture. Inspired by St. Thérèse of Lisieux, she practiced what she called "the little way"-small acts of love done with great care. She opposed contraception, abortion, and premarital sex-not out of dogma, but because she had lived the consequences. She wanted others to avoid her pain.

Faith against the war machine

Dorothy Day’s pacifism often isolated her. During World War II, she refused to support the draft. In January 1942, she published an editorial titled "We Continue Our Christian Pacifism", urging readers to reject military service. The backlash was swift. Circulation dropped. The Church pressured her to disavow communists and stop the anti-war rhetoric. She did not. Instead, she withdrew into prayer and community work. Yet her protests never stopped entirely.

In the 1950s, she was arrested for refusing to participate in civil defense drills. In the 1960s, she marched against the Vietnam War, joined draft card burnings, and faced police batons. In 1973, she was arrested one last time-for protesting with farmworkers in California at the age of 75. Not all protests ended peacefully. In 1965, a young Catholic Worker named Roger LaPorte set himself on fire in front of the United Nations. Dorothy was horrified. "That is not the way," she said.

Legacy across borders

Dorothy Day’s activism reached beyond America. In 1960, she visited Cuba and praised some of Fidel Castro’s reforms. During Vatican II, she lobbied bishops to condemn nuclear weapons. She later celebrated the council’s strong anti-war stance in The Catholic Worker. In the 1970s, she traveled to India to meet Mother Teresa, and later toured Eastern Europe. In Moscow, she defended Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, risking arrest.

She wrote about her early life with brutal clarity in books like From Union Square to Rome and The Long Loneliness. She often used her own story to address modern issues-abortion, premarital sex, poverty-not from judgment, but from hard-earned truth. Her final public speech was in 1976 at the Eucharistic Congress in Philadelphia, where she criticized organizers for choosing August 6-the anniversary of Hiroshima.

Dorothy Day died of a heart attack on November 29, 1980. She never became wealthy or comfortable. She left no fortune, only a movement. Today, The Catholic Worker newspaper still runs. The Houses of Hospitality still open their doors. And her cause for sainthood moves forward-not because she was perfect, but because she never stopped reaching for grace, even while standing in the fire.

Life of Dorothy Dayy

- 1897, November 8 - birth of Dorothy Day

- 1904 - moved to Los Angeles

- 1906 - moved to Chicago

- 1914-1916 - studies at the University of Illinois

- 1916 - moved to New York

- 1917 - first arrest and prison sentence - 30 days

- 1921, February - marriage to Berkeley Tobey

- 1924 - first autobiography *The Eleventh Virgin* published

- 1926, March 4 - birth of daughter Tamar Teresa

- 1927, December - Dorothy’s baptism

- 1933, May 1 - first issue of *The Catholic Worker* released

- 1933-1980 - serves as editor-in-chief of *The Catholic Worker*

- 1935 - *The Catholic Worker* begins publishing pacifist articles

- 1938 - second autobiography *From Union Square to Rome*

- 1942, January - article "We Continue Our Stand as Christian Pacifists" causes sharp decline in newspaper circulation

- 1952 - third autobiography *The Long Loneliness*

- 1955 - becomes a lay Dominican

- 1956 - co-founds *Liberation* magazine with David Dellinger and A.J. Muste

- 1960 - visit to Cuba

- 1971 - visits Eastern Bloc countries: USSR, Poland, Romania, and Hungary

- 1971 - receives Pacem in terris award

- 1972 - receives the Laetare Medal from the University of Notre Dame

- 1973 - last arrest, Dorothy is 75 years old

- 1974 - first Isaac Hecker Award from the Paulist Center in Boston "for commitment to building a more just and peaceful world"

- 1976, August 6 - speech at the Eucharistic Congress

- 1980, November 29 - Dorothy Day dies of a heart attack

- 1997 - beatification process begins

- 2016, April 19 - canonization process begins

sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothy_Day

- http://nczas.com/publicystyka/skandalistka-dorothy-day/

- https://www.deon.pl/215/art,187,dorothy-day-swieta-na-nasze-czasy.html

- http://www.newsweek.pl/styl-zycia/dorothy-day-swieta-komunistka,68534,1,1.html

- https://www.biography.com/people/dorothy-day-9268575

- https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dorothy_Day

- http://www.catholicworldreport.com/2013/01/03/dorothy-day-a-saint-to-transcend-partisan-politics/

COMMERCIAL BREAK

New articles in section History of the media

Jamal Khashoggi. A media trap, illusion of freedom, and price of free speech

Małgorzata Dwornik

He knew Osama bin Laden personally and advised Saudi kings, only to eventually become their greatest critic. Jamal Khashoggi entered the consulate in Istanbul and vanished without a trace, shocking world public opinion. This is the story of a man who traveled the path from palace salons to exile, paying the ultimate price for the fight for freedom of speech.

The History of The New York Times. All the news that's fit to print

Małgorzata Dwornik

In the heart of 19th-century New York, when news from across the world traveled via telegraph and the newspaper was the voice of public opinion, two ambitious journalists created a modest four-page daily that would eventually become a legend.

FORTUNE. The story of the most exclusive business magazine

Małgorzata Dwornik

Half of the pages in the pilot issue were left blank. Only one printing house in the country could meet the magazine’s quality standards. They coined the terms "business sociology" and "hedge fund". They created the world’s most prestigious company ranking. This is the story of Fortune.

See articles on a similar topic:

Hind Nawfal and Al Fatat. The first women's magazine in the Arab world

Małgorzata Dwornik

The Egyptian phenomenon, founded by the "mother of female journalists", lasted only two years in the market. However, in that short time, it accomplished so much for Arab women that it is still called a "revolutionary" today. The Arab "Girl" and its founder were the first significant female voices in this culture.

The Guardian. History of newspaper born of rage

KFi

What started two centuries ago as a cry for justice after a bloody massacre and delivering war news by balloons, became one of the most fearless newspapers on Earth. The Guardian won a Pulitzer Prize for the Snowden leaks, exposing the biggest whistleblower case in modern history.

History of De Standaard. A Flemish newspaper with a turbulent past

Małgorzata Dwornik

The first issue was supposed to reach readers on 1914. However, the outbreak of World War I disrupted these plans. It finally debuted after 4 years. It survived another war, a publication ban, bankruptcy, and the digital revolution. More than a century later, it remains strong.

Barbara Walters. The queen of impossible interviews from ABC television

Małgorzata Dwornik

Barbara Walters began her media career in 1951 with advertising and producing a children's program. In the 1960s, she shattered the glass ceiling. Her interviews on NBC brought her to the height of popularity, but it was her programs on ABC that earned her the title of the queen of television.