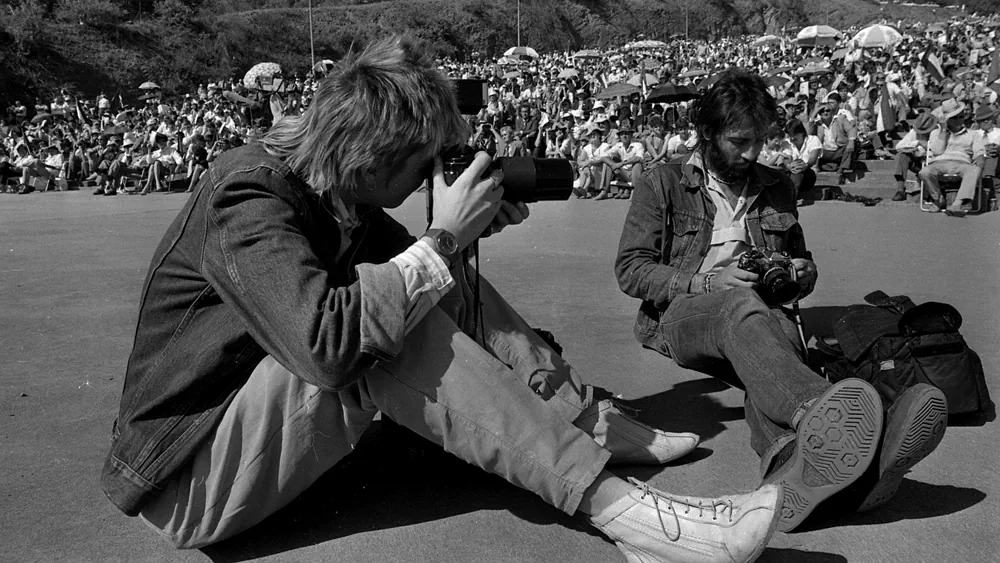

Rebecca Hearfield photographing Kevin Carter [photo: Ilagardien/CC3.0/Wikimedia]

Rebecca Hearfield photographing Kevin Carter [photo: Ilagardien/CC3.0/Wikimedia]In 1960, apartheid had already been in force in South Africa for over ten years. There were two zones of life for whites and people of color, two kinds of education, and separate documents. Mixed marriages were banned, and sexual relationships between different races were prohibited.

Against this backdrop, in Parkmore, a district of Johannesburg inhabited exclusively by white citizens, a boy was born on September 13, 1960. He was christened Kevin. His parents, Jimmy and Roma Carter, were Irish Catholic immigrants who weren’t zealous apartheid supporters but didn’t oppose it either.

Kevin, despite growing up in a Catholic family and attending a Catholic school, disagreed with his parents` views from an early age. He couldn’t understand why they supported racism and accepted the situation in the country. This led to frequent arguments at home, and Kevin felt unhappy.

Deserter, DJ, and emotional breakdown

Things worsened in 1977 when he dropped out of his pharmacy studies and was drafted into the army, where apartheid was even more pronounced. He was one of the few who defended black workers, which led to him being beaten and called a kaffir-boetie (a derogatory term meaning "friend of blacks").

His frustration grew, and in 1980 he deserted. He moved to Durban and became a DJ. His freedom was short-lived; after a few months, he lost his job and attempted suicide with a mix of sleeping pills, painkillers, and rat poison, but he was saved. He returned to the army and completed his service. In May 1983, while on duty at headquarters, he was injured in the Church Street bombing in Pretoria, which killed 19 people.

After his military service, he returned to Johannesburg and started working in a photography store, which turned out to be a positive move. Kevin quickly got drawn not only into selling cameras but also into using them, and he started taking pictures.

The photography bug and personal mission

What began as a hobby soon became a passion. Carter soon joined the Johannesburg Sunday Express as a weekend sports photographer. Photographing games on Saturdays and Sundays honed his skills, and his images became increasingly professional and lively. His eye for detail was noticed by the editor-in-chief of The Star newspaper.

Carter landed a full-time job and took on a self-imposed mission to fight apartheid. He documented all street riots, white soldiers` aggression, ethnic battles between the Zulus and Xhosas, and the activities of black Afrikaners. In 1985, he was the first to document a public execution known as necklacing, where Maki Skosana, accused of an affair with a white policeman, had a gasoline-filled tire placed around her neck and set on fire.

Carter debated whether to publish such brutal images. He later reflected, I was horrified by what they did. But then people started talking about those images... I felt that maybe my actions weren`t so wrong. Witnessing something so terrible wasn’t necessarily such a bad thing.

His photos became his weapon. In just a few years, he witnessed murders, beatings, stabbings, and gunshots through his lens. He was imprisoned several times but believed his photos, though often brutal, did more good than harm. They documented the era and were published globally thanks to his collaboration with the Daily Mirror.

In 1986, he saved a black man from a stoning by white extremists from the Afrikaner Resistance Movement. Few photographers like him existed in South Africa, where openly opposing the authorities could be deadly.

In 1990, when violence between Mandela`s African National Congress (ANC) and the Inkatha Freedom Party escalated, working as a lone reporter became extremely dangerous. Carter then gathered a group of like-minded photojournalists, forming a team that shared his mission and work. Alongside Kevin Carter, the group included:

- Ken Oosterbroek from The Star

- Greg Marinovich, freelancer

- João Silva, independent photojournalist

For the next four years, the quartet operated together, winning prestigious awards. They were present wherever violence and injustice were, amidst gunfire, machetes, and spears. Nothing and no one could stop them from recording crimes, torture, or the suffering of ordinary people on film. They confronted racism, the government, and anyone who tried to destroy humanity and the right to life. Their violent images reached newspapers worldwide. They gained fame, and in 1992, Living magazine in Johannesburg called them the Bang-Bang Paparazzi.

Bang-Bang Club

"Bang-bang" referred to gunfire and symbolized violence, but the four photographers rejected the term "paparazzi". The word did not describe what they did. They didn’t chase after sensationalism but presented the truth, and so the group’s name was changed to Bang-Bang Club.

The four friends not only worked together but also socialized, often turning to alcohol and drugs to cope with the brutal images they encountered. Marijuana, locally known as dagga, was common, but Carter mixed it with Mandrax, a banned tranquilizer. This combo, known as white pipe, initially gave extra energy before calming down. Carter often complained that he couldn’t handle the horrific sights and that stress was killing him. He needed adrenaline and motivation to continue working, so he used and continued working.

In addition to dangerous assignments in places like Soweto and Thokoza, pub meetings, and smoking dens, each friend led a relatively settled family life. Kevin Carter was the exception in the group, living freely, never settling down, though he had an illegitimate daughter, Megan.

In 1991, members of the Bang-Bang Club witnessed another brutal clash between the Zulus and ANC. Although they all took pictures, one image gained particular recognition: Greg Marinovich captured a wounded Zulu, Lindsay Tshabalala, being beaten by a Mandela supporter. A year later, for this tragic shot, the photojournalist received the Pulitzer Prize. This honor for his colleague raised the bar and motivated the others to work even harder.

The Vulture and the Little Girl. The photo that became a symbol

The names of the four South African photojournalists became globally recognized, and they began receiving offers to document stories in other countries. In March 1993, at the request of Operation Lifeline Sudan, João Silva and Kevin Carter flew to Sudan to shed light on the issue of hunger and the actions of rebels in the country. Carter, then associated with Weekly Mail, took a leave of absence, borrowed money for the flight, and joined Silva. They could not have anticipated what they would find there.

Entire villages and cities were starving. People appeared skeletal, dying in the streets. UN aid was insufficient, hence the need for the photographers` intervention. They worked tirelessly, processing what they saw. As it was time to return, while waiting for the plane, Carter went with a UN team to Juba, where a food barge was expected to arrive. To deliver aid to the starving in Ajod, they needed permission from the rebels. This process took several days, and Carter took a series of photos. When he and Silva finally reached Ajod, they managed to contact the rebels, who, in exchange for a reporter’s cheap watch, even provided an escort.

Ajod was a food distribution point for residents of nearby towns and villages. Crowds gathered there, and Carter, horrified and shocked by the sight of so many dying people, walked away from the camp to calm himself. He saw a child crawling toward the camp. Kneeling to take a photo, he saw a vulture land nearby. Feeling the gravity of the scene, Carter began taking photos without moving, hoping the vulture would spread its wings, though it didn’t. The dramatic session lasted several minutes before Carter chased the bird away. He didn’t touch the child, as he was advised not to directly interact with starving locals upon his arrival in Sudan.

He sat under a tree, lit a cigarette, and cried as the child tried again to reach the food point. Later that same day, Carter and Silva left Ajod. They were shaken, outraged, and overwhelmed by what they had seen, and Carter, in particular, couldn’t shake the incident with the vulture.

A few days after returning home, as luck would have it, The New York Times was looking for photos from Sudan. Carter offered his, and they bought the one with the vulture.

Ethical controversy surrounding inaction

On March 26, 1993, the NYT published the photo on its front page under the title The Vulture and the Little Girl, which immediately became a symbol of famine in Sudan. The image stirred strong reactions, drawing attention to Sudan and sparking global aid efforts. However, it also raised ethical questions: Was it right to take a photo at such a moment? Why didn’t he help the child? Why was he a passive observer?

The photo, sometimes captioned Struggling Girl, went around the world, evoking similar reactions and prompting the same question everywhere: Why didn’t he help, especially when the article noted the child resumed crawling toward the camp, though it was unknown if she made it.

Leslie Maryann Neal partially addressed this question in an article on https://allthatsinteresting.com/kevin-carter: He was surrounded by armed Sudanese soldiers, who were there to prevent any interference. Even if he had decided to help the child in the famous photo (initially misidentified as a girl), the soldiers would not have allowed it.

On February 21, 2011, an article on Elmundo.es included an interview with the child`s father, clarifying the gender error and subsequent events. In reality, the child in the photo was a boy named Kong Nyong, who reached the food point. To accusations that Carter didn’t help the child and the world left him to die, nurses working at the center provided this explanation:

The person in the photo wears a plastic bracelet on their right hand from the UN food station. If you look closely at the high-resolution image, you can see a blue marker code "T3". Two letters were used then: "T" indicated severe malnutrition, and "S" indicated those who only needed supplementary food. The number indicated the number of visits to the nutrition center. This means Kong was severely malnourished and had already visited the center three times. He recovered, survived the famine, the vultures, and the harshest judgments from Western readers. He died 14 years later, in 2007, of a fever.

Successes and guilt

After returning from Sudan, Carter left Weekly Mail. He initially worked as a freelancer and later signed a contract with Reuters. His photo had accomplished its purpose: it brought global attention to the issue of hunger, but it also sparked a worldwide debate about the ethics of photojournalism.

Essays, academic papers, and letters poured in. Kevin Carter found himself at the center of insults, criticism, and vulgar attacks. Even some of his friends and colleagues questioned his actions - should he have helped or not? Carter took these attacks to heart, turning to alcohol and drugs and sinking into depression.

The Bang-Bang Club and others like them stood by him. They understood what it meant to document injustice, war, and hunger and the moral decisions that had to be made in a split second. Carter often reflected on the role of a photojournalist in conveying information. Describing a shooting, he said:

I have to think visually. I close in on a tight shot of the dead guy and a red stain. I zoom in on his khaki uniform in a pool of blood on the sand. The dead man`s face is slightly gray. Here, you create an image. But inside, something is screaming, "My God". But it’s time to work. Deal with the rest later. If you can’t do this, get out of the game.

Not everyone condemned Carter and his colleagues. Many admired and appreciated the dedication they put into this line of work. A year after the famous photo was published, in April 1994, Kevin Carter received the Pulitzer Prize for feature photography. This recognition eased his nerves and guilt a bit. He accepted the award on May 23 at the Low Memorial Library Rotunda at Columbia University, writing to his parents: This is the most precious thing and the highest recognition of my work that I could receive.

An iconic photo that could have been even more powerful

While in New York, he signed a contract with the prestigious photo agency Sygma, which at the time represented the top 200 photojournalists worldwide. That same year, another famous photo by Carter captured the world’s attention. Apartheid was ending, and preparations were underway for the first free elections.

$1 trillion of global advertising market value 👇

On March 11, 1994, Carter found himself amid a bloody invasion in the rebellious small Republic of Bophuthatswana. Uniformed members of the AWB fired (from a moving vehicle) at unarmed civilians blocking the road, injuring and killing many. The Bophuthatswana Defence Force (BDF) and local police intervened to protect their citizens. They stopped the car and opened fire. Lying on the ground, with bullets whizzing over his head, Carter took pictures, later recalling:

I was wondering in which millisecond I would die and thinking about recording something they could use as my last photo.

When the shooting stopped, Bophuthatswana police allowed him to photograph the injured assailants of the civilians. Then, one of the officers approached the lying attackers and executed them. However, Carter didn’t capture this moment because…he had run out of film. By the time he loaded a new roll, it was all over. Frustrated, he drank heavily, but the photo of the injured Afrikaner Resistance Movement members moments before death circulated worldwide. There was talk of more awards for Carter. But fate had other plans.

A string of misfortunes

On April 18, 1994, just days after learning of his Pulitzer Prize, Carter gave an interview. Other members of the Bang-Bang Club had gone to Thokoza, where clashes erupted between the National Peacekeeping Force and members of the African National Congress. During the gunfire, likely from friendly fire, Ken Oosterbroek was killed, and Greg Marinovich was seriously injured. Carter heard the news over the radio. He was devastated and felt he should have been the one to die.

Things weren’t going well with Sygma either. A failed trip to Cape Town and a canceled interview with Mandela due to bureaucracy, followed by a disappointing report on the French president`s visit, frustrated him. The office wasn’t happy with the report: too late…poor quality photos. Carter became increasingly despondent, mentioning suicide. He was also struggling financially.

When Time magazine offered him an assignment in Mozambique (covering the first free elections) in mid-July 1994, he eagerly accepted. Unfortunately, on the return journey, he left his film in the airplane. It was never recovered, and this seemed to be the final straw.

July 27, 1994…

Around 9:00 PM, Kevin Carter reversed his red Nissan pickup under a blue eucalyptus tree at the Field and Study Center. He often played there as a boy. The Sandton Bird Club was holding its monthly meeting, but no one saw Carter as he attached a garden hose to the exhaust pipe with silver duct tape and ran it through the passenger window. Dressed in unwashed Lee jeans and an Esquire T-shirt, he climbed in and started the engine. Then he turned on music on his Walkman, laid on his side, using his backpack as a pillow.

(Scott MacLeod, https://www.lehigh.edu/~jl0d/J246-02/carter.html)

An emotional burden too heavy to bear

On the passenger seat was a farewell note: I am really, really sorry. The pain of life overrides the joy to the point that joy does not exist. Depressed…without phone…money for rent…money for child support…money for debts…money!!! I am haunted by vivid memories of killings and corpses and anger and pain…of starving or wounded children, of madmen with guns, often police, of executioners. I will join Ken if I am that lucky.

Kevin Carter was only 33 years old, carrying a burden of images too great to bear. Neither alcohol nor drugs could help. For his tormented soul, death brought relief. He left behind thousands of photographs that, to this day, evoke waves of emotion. The ethical questions of his profession are still debated. But without Carter and others like him, the world would not know many harsh truths. As a Sudanese proverb says: Those who have not seen evil cannot appreciate the good.

Carter is gone, the Bang-Bang Club ceased to exist, apartheid fell, but the memory of those days remains. In 2000, Marinovich and Silva published the book The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots from a Hidden War, which in 2010, was adapted into a feature film by Steven Silver titled the same. Canadian actor Taylor Kitsch portrayed Kevin Carter.

In 2004, Dan Krauss directed the short film The Death of Kevin Carter: Casualty of the Bang Bang Club, which was nominated for an Academy Award two years later. Carter has also become the subject of songs. The band Manic Street Preachers included a track titled Kevin Carter on their fourth album, and the album Poets and Madmen by the band Savatage tells the story of his life.

Kevin Carter`s legacy is timeless. His photos continue to move hearts and minds. His memory is honored by a foundation established in his name after his death, which supports emerging photographers (including mental health support), organizes workshops, and hosts exhibitions.

It took years of experience and understanding to reach this point, which should not be forgotten. His photographs capture the triumphs and tragedies of the human experience with unwavering honesty and empathy.

(Stephen Walton, September 7, 2023)

Timeline of Kevin Carter:

- 1960, September 13 - Kevin Carter was born

- 1977 - Carter joined the South African Air Force

- 1980 - Desertion and work as a DJ

- 1981 - Return to the military

- 1983, May - Carter was injured in a bombing

- 1983, autumn - Kevin took a job in a photography store and worked as a weekend reporter for the Johannesburg Sunday Express

- 1984 - Full-time position at The Star

- 1985 - Carter was the first to document the execution known as "necklacing"

- 1990 - Formation of the group of four reporters, named the Bang-Bang Club in 1992

- 1993, March - Carter flew to Sudan and took the famous "Vulture and Child" photo

- 1993, March 26 - The New York Times published the photo with the vulture

- 1994, March 11 - Carter took his second most famous photo during an execution in Bophuthatswana

- 1994, April 12 - Pulitzer Prize awarded to Kevin Carter

- 1994, April 18 - Ken Oosterbroek, a member of the Bang-Bang Club and Carter`s friend, was killed

- 1994, May 23 - Pulitzer Prize ceremony in New York and signing with Sygma agency

- 1994, July 20 - Trip to Mozambique

- 1994, July 27 - Kevin Carter committed suicide

Sources:

- https://www.lehigh.edu/~jl0d/J246-02/carter.html

- https://time.com/archive/6725984/the-life-and-death-of-kevin-carter/

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/kevin-carter

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kevin_Carter

- https://grochowska.pl/struggling-girl-kevin-carter/

- https://allthatsinteresting.com/kevin-carter

- https://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2011/02/18/comunicacion/1298054483.html

- https://medium.com/@aftab4092/the-life-and-legacy-of-kevin-carter-truth-trauma-and-the-power-of-photography-071ac89a4a3c

- https://www.iphotography.com/blog/kevin-carter-photography/

- https://foto-info.pl/kevin-carter-1960-1994.html

- https://www.gettyimages.com/sets/xaYpPIV1rki84ky1mg-0qg/photographer-profile:-kevin-carter

- https://www.theguardian.com/media/2014/jul/30/kevin-carter-photojournalist-obituary-archive-1994

- https://www.lightrocket.com/blog/where-ethics-and-photography-meet-a-closer-look-at-kevin-carter

- https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/blink/watch/the-vulture-in-the-frame/article9901741.ece

- https://aboutphotography.blog/blog/the-haunting-legacy-of-kevin-carters-1993-sudan-famine-photograph

COMMERCIAL BREAK

New articles in section History of the media

Jamal Khashoggi. A media trap, illusion of freedom, and price of free speech

Małgorzata Dwornik

He knew Osama bin Laden personally and advised Saudi kings, only to eventually become their greatest critic. Jamal Khashoggi entered the consulate in Istanbul and vanished without a trace, shocking world public opinion. This is the story of a man who traveled the path from palace salons to exile, paying the ultimate price for the fight for freedom of speech.

The History of The New York Times. All the news that's fit to print

Małgorzata Dwornik

In the heart of 19th-century New York, when news from across the world traveled via telegraph and the newspaper was the voice of public opinion, two ambitious journalists created a modest four-page daily that would eventually become a legend.

FORTUNE. The story of the most exclusive business magazine

Małgorzata Dwornik

Half of the pages in the pilot issue were left blank. Only one printing house in the country could meet the magazine’s quality standards. They coined the terms "business sociology" and "hedge fund". They created the world’s most prestigious company ranking. This is the story of Fortune.

See articles on a similar topic:

Il Foglio. History of italian daily whose founder hid behind an elephant

Małgorzata Dwornik

The first issues lacked photos but featured drawings and caricatures. Editorial articles appeared only on the third page, and all texts except columns were anonymous. This was how the first issue of the new daily newspaper, published in Milan in 1996, looked. A newspaper that, uniquely in Italy today, does not incur losses.

Dorothy Day story. Journalist, feminist and saint candidate

Małgorzata Dwornik

She fought poverty with fire, defied war with silence, and prayed with clenched fists. Dorothy Day, once a communist and always a fighter, now walks the path to sainthood. Her journey from rebellion to devotion still divides and inspires. This is the story of "the rebel saint".

POLITIKA. The history of Serbia's oldest daily newspaper

Małgorzata Dwornik

In 1904, journalist Wladislaw F. Ribnikar founded Serbia's first independent newspaper. Opponents predicted a quick failure for Politika, the government viewed it with suspicion, but readers... were captivated by its new quality. Ribnikar laid the foundations for modern Serbian journalism, but his successors faced mixed fortunes.

The Guardian. History of newspaper born of rage

KFi

What started two centuries ago as a cry for justice after a bloody massacre and delivering war news by balloons, became one of the most fearless newspapers on Earth. The Guardian won a Pulitzer Prize for the Snowden leaks, exposing the biggest whistleblower case in modern history.