He arrived in the United States as a young volunteer. He came to fight in the Civil War, landing on a continent where he barely knew the language. Did he know he was destined to redefine American journalism?

The journey started far from the publisher`s office. Born on April 10, 1847, Joseph Pulitzer grew up in Makó, Hungary. This town lay about 200 kilometers from Budapest. The region was famous for growing onions and garlic. His father, Fülöp Pulitzer, was a respected merchant. The family was wealthy enough for Fülöp to retire early.

They moved to Pest in 1853, and the family grew large. They eventually counted ten children in total. The children received education from private tutors, learning German and French. Life took a sharp turn in 1858. His father died, and his company went bankrupt. This plunged the large family into poverty.

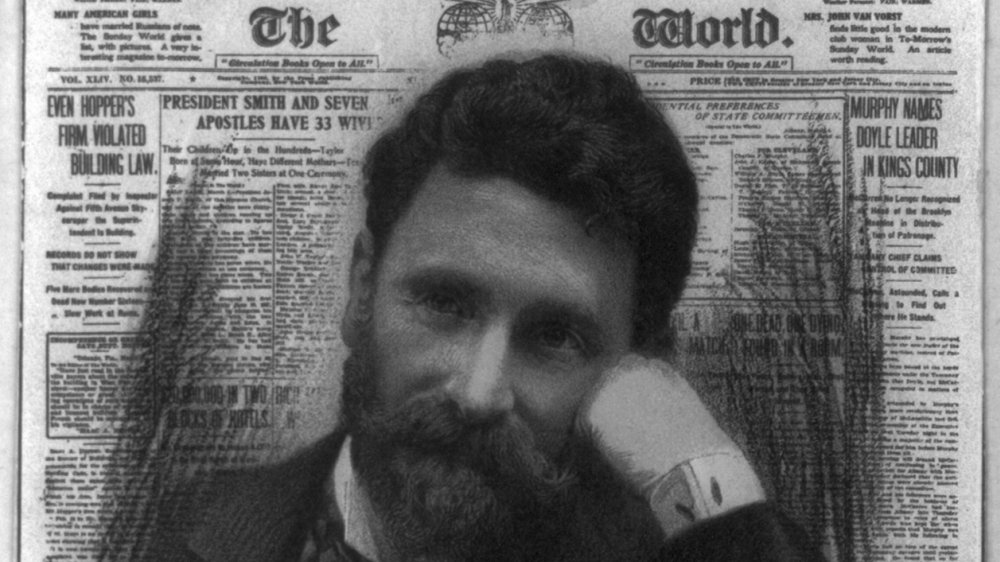

Chromolithograph depicting Joseph Pulitzer with his newspapers in the background.

Chromolithograph depicting Joseph Pulitzer with his newspapers in the background.[source: Library of Congress USA, public domain]

Seeking a uniform and a new home

Young Joseph wanted adventure, not commerce. He dreamed of joining Napoleon’s army or the famous Foreign Legion. But poor eyesight blocked these military plans. Did this stop the resourceful Hungarian? Of course not. He traveled to Hamburg, hoping to find recruiters for the American army. The Civil War was raging and needed thousands of volunteers.

No one questioned the seventeen-year-old’s health. He was immediately shipped out on a boat bound for Boston. He landed and headed straight for New York. There, he joined the 1st New York Cavalry Regiment. This unit operated under Philip Henry Sheridan. He chose the cavalry because it included many Germans. He did not speak English at all when he signed up.

The war ended, but his search for stability continued. He searched for his place and for money across the country. He ended up sleeping in railway cars. He wandered through New York and New Bedford, Massachusetts. Finally, he settled in St. Louis, Missouri. This felt like his promised land. St. Louis welcomed German speakers, which made life easier for him. Meanwhile, he polished his English skills. He spent his days in the municipal library.

Mule driver, waiter, and the five dollar fraud

He had to take many jobs to survive. One day, he saw an advertisement in the local paper, Westliche Post. The ad sought mule drivers-or "mulików"-at Benton Barracks. He took the job but quit after only two days. The mules proved capricious, and the food was awful.

Pulitzer later summarized his short-lived career with an iconic quote: "The man who did not care about sixteen mules does not know what work and trouble are". He tried to work as a waiter next. He found a job at the famous Tony Faust restaurant. This spot was popular with members of the St. Louis Philosophical Society. Among them was Henry C. Brockmeyer, a translator of Hegel.

Pulitzer was fascinated by the master and his works. He served Brockmeyer drinks and pretzels with such dedication that one time, the ordered beer spilled. The beverage ended up on the philosopher’s trousers. He was fired immediately.

Pulitzer suffered from poor health. Hard physical labor simply did not suit him. His temperament and pride did not match waiting tables or herding mules. Instead, he devoured books at the library. He developed a keen interest in law. Then came the incident that launched his career. He saw a job advertisement for a sugar plantation in Louisiana. He and dozens of others paid the recruiter five dollars. They boarded a ship and sailed away.

It turned out to be a complete scam. There was no job to be had. What did he do when he returned? He described the entire fraud in detail. He took the text to the Westliche Post, and they published it. This was Pulitzer’s first published article.

From debt collector to editor-in-chief

The Westliche Post office also housed a law firm. William Patrick and Charles Phillip Johns often helped the young man. They assisted him particularly with legal aspects of his writing. They recognized his determination to learn. They made room for a desk in their office.

The Hungarian Jew received American citizenship on March 6, 1867. A year later, he passed his law exams. He still struggled with broken English. He also dressed in a specific way. Consequently, law clients did not trust him with their cases. He handled translating papers and collecting debts instead.

Yet, this did not stop his fierce arguments or his writing. Carl Schurz, the editor-in-chief of the Westliche Post, valued this talent. In 1868, Schurz offered Joseph a full-time journalist position. His career accelerated instantly. He worked up to 16 hours a day.

He joined the Philosophical Society. He met thinkers like Joseph Keppler and Thomas Davidson. He even debated Henry Brockmeyer, the master he once spilled beer upon. As a new American citizen, he entered politics. He identified with the Republican Party. He joined their ranks. On December 14, 1869, his candidacy for the Missouri State Assembly was accepted unanimously. He was only 22 years old. He threw himself into rallies and meetings with huge energy. This effort paid off with a victory of 209 to 147 votes.

He was still called "Joey the German" or "Joey the Jew". On January 5, 1870, he participated in the Assembly session in Jefferson City. He lived there for almost two years. All the while, he continued his newspaper work. He climbed the journalism ladder. He became the editor-in-chief of the Westliche Post. He wrote, printed, and earned more and more money.

In 1872, he bought company shares for 3,000 dollars. He sold them for a profit the following year. With the money he earned, he bought two newspapers:

- The St. Louis Dispatch

- The St. Louis Post

He merged them into a single daily paper. This became the Post-Dispatch. He became his own master.

From corruption fighter to media titan

His political activities did not fare as well as his journalism. Pulitzer grew disappointed with the corruption plaguing the Republican Party. He left and switched to the Democratic Party. From 1880, he guest-published in The Washington Post. That paper sympathized with the Democrats.

Relationship and tech. Study about love in the age of likes 👇

In 1884, he was elected to the US House of Representatives. He represented a New York district as a Democrat. He divided his time between the newspaper and politics from March 4, 1885, to April 10, 1886. Ultimately, he resigned from politics. As an owner and journalist, he declared a strong mission:

- Fighting corruption and injustice.

- Maintaining partisan independence.

- Opposing privileged classes.

- Helping the poor seek social reforms.

Pulitzer’s personal life also stabilized. He married five years younger Katharina "Kate" Davis in 1878. Kate came from high society. She was related to Jefferson Davis, the former President of the Confederate States of America.

They had seven children, five of whom survived to adulthood. Kate managed the home and children. She intervened in her husband`s affairs only regarding charity. The Pulitzers became deeply involved in the construction of the Statue of Liberty. They contributed their own funds. They also organized a nationwide collection drive for the cause.

Sensationalism and the new york world gamble

Pulitzer became a wealthy man very quickly. In 1883, he bought his second newspaper. It was the New York World. He paid 346,000 dollars for it. The paper was unprofitable at the time. The Post-Dispatch was successful, but he needed to increase the circulation of his new New York acquisition. He made a crucial discovery that changed the press forever. He discovered that "Sensationalism and gossip sell better".

He immediately steered the paper in this direction. The pages filled with stories detailing scandals, corruption, and rumors. New York World articles fiercely criticized many systemic issues:

- Tax fraud.

- Fiscal privileges for corporations.

- Lack of civil service reform.

- Corrupt officials.

- The practice of vote-buying.

- Forcing employees to vote as their employer wished.

- Lotteries and gambling.

The newspaper’s circulation soared quickly.

The birth of the yellow kid and bly’s experiments

To keep the momentum going, Pulitzer hired Richard F. Outcault in 1885. Outcault was a cartoonist and artist. He introduced a series of thematic drawings. This marked the beginning of the comic strip in the New York paper. The theme centered on life in the slums.

In 1887, Nellie Bly began publishing sensational articles in New York World. This investigative journalist stirred up controversy with her texts. Bly often worked "under cover". She wrote immersion articles about poverty and poor working conditions. She detailed crumbling houses where people lived.

She took her dedication to an extreme level. She faked insanity to enter the asylum on Blackwell Island. She wanted to see how the patients lived. Her powerful articles led directly to necessary reforms in the field. Bly, supported by Pulitzer, executed another spectacular feat. She aimed to beat the record from Jules Verne’s book, Around the World in Eighty Days. Bly successfully circumnavigated the globe.

Her final time was 72 days, 6 hours, 11 minutes, 14 seconds. Crowds greeted her upon her return. This brought fantastic publicity to the newspaper. Pulitzer purchased a four-color printer in the spring of 1893. This was a true revolution. A colorful Sunday satirical supplement appeared.

When Outcault joined the team, color and satire conquered not just New York, but the entire US. On September 16, 1894, a full-page comic appeared in New York World. The title was "Ignorance of Uncle Eben`s City". It depicted African Americans and Irish immigrants from the Possumville slums, all in color.

On January 13, 1895, Outcault introduced the famous bald boy in a dress. This was in the Hogan’s Alley series. The boy was named Mickey Dugan. When the boy`s dress became yellow, he captivated readers. He received a new name: The Yellow Kid. This yellow character became the cause of a major press war.

War with hearst and the newsboys strike

In 1895, William Randolph Hearst entered the scene. He was a Californian copper and silver magnate and a journalist. Hearst bought the New York Journal, which belonged to Joseph’s brother, Albert Pulitzer. Hearst had gained his first experience during summer internships at Pulitzer’s paper. Years later, he decided to challenge his former employer.

7 facts about news on social media 👇

Hearst hired top professionals like journalist Sam S. Chamberlain and writer Ambrose Bierce. He turned the newspaper around in a single year. He increased its circulation by 100%. Hearst also invested heavily in photographs. The war escalated when Hearst poached Outcault. Outcault took The Yellow Kid character with him. Pulitzer immediately hired Georg Luks to continue the Hogan’s Alley series and the yellow boy. Two New York papers ended up featuring the exact same character.

The competition became sharp and brutal. Neither man held back. They poached staff and printed unverified, sensational stories. They only cared if the story was more sensational than the rival`s. This media conflict earned the name yellow journalism. The term came from The Yellow Kid character. The peak of this media battle lasted from October 1896 to the spring of 1898.

The Cuban conflict became the climax. When Cubans protested against Spanish rule, both men competed intensely for information about Cuba. They reported concentration camps and starving children. It later turned out that none of this information had any basis in reality. However, newspaper circulation dramatically increased.

Tragedy struck Havana on February 15. The USS Maine cruiser stationed there exploded. 266 crew members were killed. Voices immediately demanded an attack, and both newspaper giants called for war with Spain. It quickly became clear the explosion was an accident. This fact did not deter the two journalists. They continued printing manufactured sensations.

Pulitzer was the first to withdraw from the struggle. This decision related to the Newsboys Strike that erupted in 1899. When the Spanish-American War did break out, news flooded in. Newspaper circulation increased. Many publishers raised prices. Pulitzer and Hearst led the way.

Distribution relied on juvenile newsboys. After the war, demand fell. Some returned to lower prices, but the two warring magnates did not. The newsboys launched a massive strike on July 21, 1899. They occupied the Brooklyn Bridge. This halted traffic and distribution of news to many New England cities. The strike lasted two weeks, until August 2. The newsboys successfully achieved lower prices and wage increases. However, New York World circulation plummeted. It fell from 360,000 to 125,000 copies.

The legacy of the prize and the final words

Approaching 57 years old, Joseph Pulitzer increasingly suffered from health ailments. Blindness, lung problems, and hearing loss forced him to retire from managing his newspapers. Frank I. Cobb became the editor-in-chief of the World in 1904. He did not have an easy life. The owner interfered in everything. Pulitzer demanded reports. He decided what to print and who should write. Cobb managed to cope, though.

They only agreed on one major political point. They both supported Woodrow Wilson for president. Pulitzer officially handed the legacy to his son, Ralph, in April 1907. He wrote a statement announcing his decision. All New York newspapers printed his words. The only exception was the New York World.

The magnate was furious. However, Cobb stood firm. The owner eventually backed down. He began to appreciate the editor-in-chief’s work. He finally allowed Cobb to act independently. Frank I. Cobb only published Pulitzer’s resignation after his death.

As early as 1892, Joseph proposed establishing a school for young journalists. He suggested the idea to the Columbia University rector, Seth Low. Pulitzer also offered to finance it, but Low refused. The plan only succeeded in 1903 with the support of Nicholas Murray Butler.

In his will, he bequeathed 2 million dollars to the young journalism adepts. Suffering greatly, he spent his final years on his yacht, the Liberty. He died there on October 9, 1911. His German secretary was reading him a story about King Louis XI.

When the secretary finished, Joseph Pulitzer uttered his final words in German: "Leise, ganz leise" (Quietly, quite quietly). He was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, New York. The Columbia School of Journalism was established a year after his death. Columbia University awarded the first Pulitzer Prizes in 1917.

60% of digital creators do not verify information before publishing 👇

The award is now determined by a 19-person board. It is granted in 21 categories related to journalism, literature, and music. Though Pulitzer had envisioned that journalists would award journalists, the board today includes people related to journalism but not necessarily practicing journalists.

Despite his controversial past, his words remain an enduring "Golden Thought" for American media. This quote was said during a conversation with philosopher Professor Thomas Davidson: "Every reporter is a hope, every editor is a disappointment". Another maxim from the time of his press war with William Randolph Hearst defines his writing style: "Never print anything your maid cannot understand".

*****

Sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Pulitzer

- http://www.pulitzer.org/page/biography-joseph-pulitzer

- https://www.polskieradio.pl/39/156/Artykul/1270721,Joseph-Pulitzer-%E2%80%93-tworca-nowoczesnego-dziennikarstwa

- http://spartacus-educational.com/Jpulitzer.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_World

- http://www.pulitzer.org/page/biography-joseph-pulitzer

COMMERCIAL BREAK

New articles in section History of the media

Jamal Khashoggi. A media trap, illusion of freedom, and price of free speech

Małgorzata Dwornik

He knew Osama bin Laden personally and advised Saudi kings, only to eventually become their greatest critic. Jamal Khashoggi entered the consulate in Istanbul and vanished without a trace, shocking world public opinion. This is the story of a man who traveled the path from palace salons to exile, paying the ultimate price for the fight for freedom of speech.

The History of The New York Times. All the news that's fit to print

Małgorzata Dwornik

In the heart of 19th-century New York, when news from across the world traveled via telegraph and the newspaper was the voice of public opinion, two ambitious journalists created a modest four-page daily that would eventually become a legend.

FORTUNE. The story of the most exclusive business magazine

Małgorzata Dwornik

Half of the pages in the pilot issue were left blank. Only one printing house in the country could meet the magazine’s quality standards. They coined the terms "business sociology" and "hedge fund". They created the world’s most prestigious company ranking. This is the story of Fortune.

See articles on a similar topic:

Dorothy Day story. Journalist, feminist and saint candidate

Małgorzata Dwornik

She fought poverty with fire, defied war with silence, and prayed with clenched fists. Dorothy Day, once a communist and always a fighter, now walks the path to sainthood. Her journey from rebellion to devotion still divides and inspires. This is the story of "the rebel saint".

The Beginnings of Periodical Publishing in Poland

Bartłomiej Dwornik

The first printed works - non-periodical "flyer newspapers" - appeared in Poland in the early 16th century. They were published only for significant occasions to describe these events, sometimes even in verse.

History of The Honolulu Advertiser. From missionaries to a merger with rival

Małgorzata Dwornik

It was created to outdo unreliable competition. Early world news arrived via boat. It didn’t hire Mark Twain, but Jack London wrote for it. The story of Hawaii’s oldest newspaper spans 154 years of ups, downs, and radical changes in direction. In 2010, to survive a losing war of attrition with its biggest rival, it had to merge with it.

#mediaHISTORY podcast. Listen on Youtube, Spotify or Apple Podcasts [LINK]

Reporterzy.info

History of media and journalism. The biggest titles, famous journalists, groundbreaking events in the press, radio, television and internet industries in the world. Stories developed and told by Małgorzata and Bartłomiej Dwornik from the online weekly Reporterzy.info.