illustrations: journaldemonaco.gouv.mc

illustrations: journaldemonaco.gouv.mcOn the shores of the Mediterranean, within the French Riviera, lies the city-state of Monaco, officially known as the Principality of Monaco. Covering only 2.02 square kilometers and with a population of just under 40,000, it has its own government, with a prince as the head of state - currently Albert II Grimaldi.

This tiny piece of land gained independence in the 15th century, recognized by the King of France and the Pope. Over the centuries, Monaco came under the influence of France, Italy, and Spain. Finally, in 1861, it achieved full independence through a treaty with France. Before that, from November 20, 1815, Monaco was under the protectorate of the King of Sardinia. While the principality was francophile, the two most important towns in the region, Menton and Roquebrune, sided with Italy and seceded in 1848. Border and sovereignty issues remained a topic of high-level discussions until Napoleon III and Charles III addressed them in 1861.

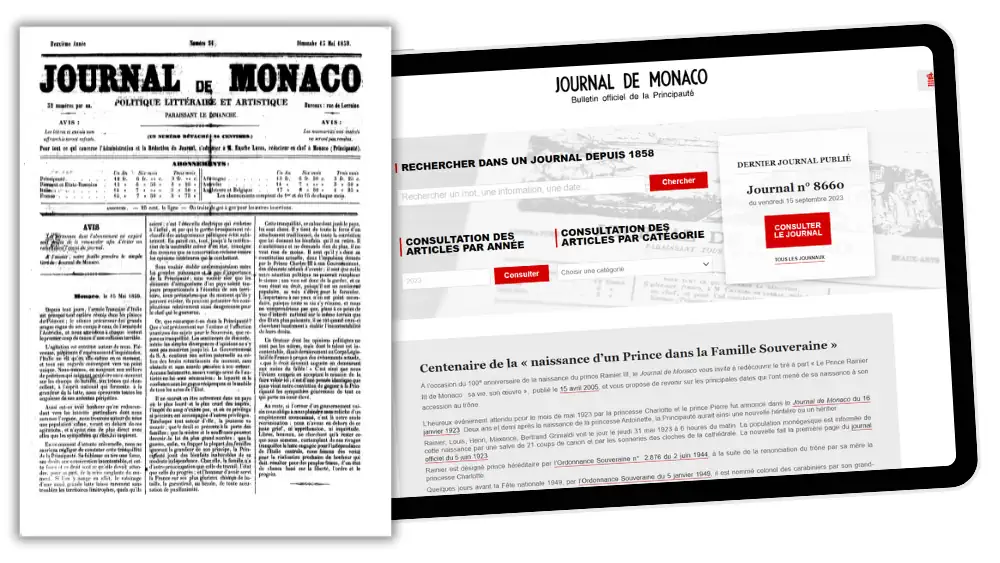

Before these events, in 1858, Carles de Lorbac founded the weekly L’Eden to raise awareness of Monaco`s issues, later renamed Journal de Monaco, which continues to this day. Lorbac, a writer and contributor to French newspapers like Le Nord and Le Gaulois, was no stranger to journalism.

Sunday editions

The first issue of L’Eden, published on May 30, 1858, consisted of four pages with three columns and bore the subtitle Journal de Monaco, paraissant tous les dimanches (Monaco`s newspaper, published every Sunday). Although Italian was the official language at the time, and locals spoke the Ligurian dialect, the new publication was printed in French.

The first page of the inaugural issue featured an engraving of a castle, mountains, and vast water expanses (not a real view, as clarified by the editors) and a note that future issues would include other illustrations by renowned artists. Literature and fine arts were the main themes.

The initial two-page articles, authored by editor-in-chief Lorbac, described the nature of the most beautiful corner of the world and the construction of new casinos for tourists. Page three provided regional news, mainly from Nice, and local updates edited by Eusebe Lucas, who also dedicated significant attention to music. The last page was reserved for advertisements.

Subsequent issues followed a similar format. Lorbac not only wrote on current topics but also reviewed books, concerts, and theater performances. In the second issue, published on June 6, 1858, the recurring column Causeries - A Madame C* featured an article on the life and works of Frédéric Chopin.

From the third issue onward, a weather column became a permanent feature, and subsequent weeks included serialized novels, schedules of arriving ships, and more engravings. Interest in the weekly grew not only among Monaco`s residents but also among the many tourists drawn to the area`s numerous casinos, which Lorbac readily advertised in his paper.

By the end of the year, the following columns became regular fixtures in the weekly:

- Italian Bulletin (mainly tourist information)

- concert programs

- health columns

As promised in the first issue, most content focused on culture and the arts. Politics was entirely absent, and world news was limited to short, concise statements reprinted from French newspapers.

The end of Eden, the beginning of the Journal

May 1859 brought changes in the editor-in-chief position and slight modifications to the newspaper`s appearance. Eusebe Lucas took over the main editorial office, and the weekly was renamed Journal de Monaco. The declaration of "broad literature" disappeared, though general arts coverage remained.

Order and structure dominated the pages of the newspaper. Pages one and two featured Monaco news, a Local Chronicle, and News on Literature and Art. Editorial articles always led, with Lucas addressing the country`s main issues. Page three contained novel excerpts, while page four remained dedicated to advertisements, with weather updates and ship schedules also moved there. Starting with issue 51, dated May 15, 1859, the subtitle became Politique, Littéraire et Artistique (Politics, Literature, and Art).

Interest in Monaco`s culture and history grew so much that, in November 1859, a French branch of the newspaper was launched in Paris. Initially run by Madame Cendrier, editor at the Imperial Conservatory, it was later taken over by M. St-Hilaire, a music editor. At readers` request, the weather column returned to the front page. On April 29, 1860, the 100th issue of Journal de Monaco was published.

Groundbreaking issue 154

The year 1861 brought significant changes for the tiny country. Following an April 1860 plebiscite, Napoleon III and Charles III Grimaldi signed a treaty on February 2, 1861, granting Monaco full independence in exchange for 4 million francs and 90% of its territory and resources (Menton and Roquebrune became part of France). The law took effect in April, and the Journal de Monaco informed residents of the principality. Issue 154, dated April 28, 1861, published Napoleon`s decree and an explanatory note. Not everyone was pleased with this development. Among the dissatisfied was Eusebe Lucas, who announced in the same issue that he would leave the editorial team as of May 1.

"Monaco`s future is now secure in every respect, and the voice of our weekly played no small role in this. That satisfaction is enough for us", Lucas wrote in his final article.

After his resignation, the newspaper operated on momentum. M. Avia de Phrygie temporarily took the helm, but it was clear the weekly needed a strong leader. On August 4, 1861, the Journal published a mere two pages, along with an apology, citing editorial changes as the cause.

A week later, readers were greeted by the new editor-in-chief, Emile Bouchery. Bouchery was an experienced journalist, having worked for French newspapers such as La Patrie and Le Figaro. In his open letter to readers, he declared:

- openness to the world and region

- listening to readers` opinions

- introducing innovative visions

- improving the professionalism of the writing

- promoting the benefits of Monaco`s resorts

- reaching an elite group of readers

- maintaining the traditions and customs established by predecessors

The weekly quickly returned to its established course. The 51-year-old editor performed exceptionally well, especially considering the recent opening of a second branch office in Nice. However, a year later, in July 1862, he thanked everyone for their cooperation and handed over the reins to Rubini Etienne.

By the end of the 1860s, six more editors-in-chief led the main editorial office of the Journal de Monaco:

- Edmond Delère (from September 14, 1862)

- Alphonse Chambon (from May 17, 1863)

- Auguste Marcade (from October 9, 1864)

- A. Dalbera

- Hyacinthe Giscard (from November 5, 1865)

- Alfred Garbiè (from July 20, 1869)

The first three managed the magazine for one-year terms. Only Hyacinthe Giscard held the position for nearly four years, followed by Alfred Garbiè, who served for seven years. Between these terms, A. Dalbera`s name occasionally appeared, seemingly as the weekly`s fallback editor. His name also reappeared in the following decade.

Tuesdays better than sundays and no competition

Despite frequent changes in leadership, the weekly maintained its high standards. Each new editor wrote most of the articles, and their interests dictated the prevailing topics. Delère favored tradition and health, introducing a poetry corner ("something for the soul"). Chambon focused on the region`s economy and agriculture, while Marcade delved into the history of ruling families.

Giscard introduced some innovations: "Without neglecting articles of local importance more than in the past, we will introduce new and powerful elements of interest. In the Miscellaneous column, we will cater to all intellectual cravings in literature, poetry, or travel journals".

When Alfred Garbiè assumed the editor`s chair in July 1869, Journal de Monaco was already well-established, reputable, and professional, with clearly defined sections and columns:

- Actes Officiels (official acts)

- Nouvelles Locales (local news)

- Chronique du Littoral (coastal chronicle)

- Courrier de Paris (Paris courier)

- Nouvelles Diverses (miscellaneous news)

- Courrier D’Italie (Italian courier)

- Feuilleton du Journal de Monaco (serial story)

- Lettre d’un touriste (letter from a tourist)

- Chronique Belge (Belgian chronicle)

- Variétés (varied topics)

Not all sections appeared in every issue. The weekly still had only four pages. Engravings, even in advertisements, had long disappeared. Each issue included a weather forecast, shipping schedules, serialized novels, and concert schedules. Starting March 9, 1869, the newspaper was published on Tuesdays.

New contributors increasingly appeared as private correspondence. Emile Montany wrote from Paris, while Georges Henri reported on Belgian affairs.

Until the 1890s, Journal de Monaco faced virtually no competition. What little press existed relied on newspapers and magazines imported from France or Italy. The local media scene was sparse, making the weekly popular and widely read. It provided extensive information on local entertainment. Hotels, casinos, and restaurants eagerly advertised in the paper, contributing to its revenue.

Casino profits and other gaming revenues were so high that Prince Charles III abolished personal, capital, and property taxes on February 8, 1869, an announcement carried by the Journal as part of its official role. This ushered in an era of construction, during which Monaco saw the opening of an opera house. However, the birth of true press in Monaco is dated to the late 1880s.

The stock market, finance, and pigeon shooting

For nearly seven years, Alfred Garbiè managed Journal de Monaco, introducing new topics. Global news appeared under columns like Bulletin des Cours and Faits Divers. A novelty was Causerie (Conversations), featuring articles on human communication, legal news, and decorative horizontal lines separating topics. This gave the paper a lighter feel. Until then, only headlines served as buffers, causing section content to blend together.

News and gossip from Parisian streets were found under the headline Lettres Parisiennes (Parisian Letters), written by a regular correspondent using the pseudonym Bachaumot.

On May 30, 1876, Alfred Garbiè bid farewell to the Journal and Monaco. The same day, the masthead once again featured the name A. Dalbera. On June 6, 1876, the column La Semaine à la Bourse (The Week on the Stock Market) debuted, followed a week later by La Semaine Financière (The Financial Week).

This time, A. Dalbera`s tenure as chief editor lasted longer, ending on May 23, 1882. During his six years, Dalbera proved himself deserving of the position.

On August 28, 1877, the 1000th issue of the Journal was published, marking its 20th year. In January of the following year, a sports column debuted. While athletics were popular, pigeon shooting competitions dominated the section. Reports on international events fascinated readers. Wealthier readers enjoyed updates on art auctions.

Thanks to its casinos, Monaco thrived economically and culturally. Many theater and cabaret stages emerged, covered extensively by the Journal. Their current repertoires were regularly printed. When the opera opened in 1879, it too found a place in the principality`s premier media outlet.

A fresh look, railways, and telephones

On May 30, 1882, issue 1244 introduced a new editor-in-chief, M. F. Martin. Over the next 11 years, the Journal de Monaco underwent several evolutions, especially as new competitors emerged in the media market by the decade`s end. Engravings returned, though used exclusively in advertisements.

With the arrival of railways in Monaco, the newspaper began publishing train schedules, catering to tourists from Paris and Marseille. Despite the lively entertainment scene, significant attention was given to religion, events, and places associated with it. A dedicated column, Cathédrale de Monaco, appeared regularly on the front page. Various supplements began to appear, primarily addressing official matters, such as the one published on December 28, 1886.

On January 1, 1889, the magazine`s long-standing layout saw changes. Although the three-column, four-page structure remained, the front page was reorganized, clearly separating news from articles. It was noted that the publication was a weekly available in Monaco, France, Algeria, and Tunisia. Individual pieces of news were distinctly separated. A new column, Courrier de la Semaine (The Week`s Mail), offered a roundup of major world events.

The mysterious Bachaumot was replaced by an equally enigmatic Dangeau. The printing quality also improved, possibly due to new machinery. By the end of the century, communication improved further as telephones appeared in Monaco and the Journal`s editorial office.

Competition from Monte Carlo

The 1890s brought Monaco more fame (Monte Carlo) and a new media market. By 1889, publications such as the weekly Monte-Carlo mondain ("Worldly Monte Carlo"), the daily Le Petit Monégasque ("The Little Monaco"), and the magazine Les Rives d’or ("The Golden Shores") had emerged. Many of these were printed in the increasingly popular Monte Carlo, and nearly all were illustrated, attracting readers.

The ruling authority, under the new Prince Albert I, took Journal de Monaco under its wing, making it the exclusive platform for official decrees, announcements, and laws while continuing to promote the culture and art of the region.

On November 1, 1894, Louis Aurèglia became the new editor-in-chief of Journal de Monaco. Aurèglia, an excellent leader and manager, steered the publication for over 35 years. He guided the paper into the new century, reported on the principality`s first constitution, and followed the lives of Monaco`s citizens on the front lines of World War I.

During his initial years, Aurèglia reorganized the importance of information, grouping content thematically under sections like Chronique Artistique and Echos et Nouvelles (Echoes and News). He added subtitles to sections, separated them with decorative lines and different fonts, renamed columns (e.g., Chronique du Littoral to Sur le Littoral (On the Coast)), and introduced new topics. Articles on science and technology appeared under the Science column, often based on interviews with scientists - a novelty at the time.

Regional history over global concerns

Entering the new century, Journal de Monaco was transparent, organized, and supported by the highest authorities. The first decade of the century was relatively peaceful, though global events, especially in China, began to attract attention. The 1908 London Peace Conference on disarmament brought little optimism, especially as Russia grew restless.

Meanwhile, Monaco continued its lifestyle of casinos and tourism. In December 1909, the paper introduced a new column, Etudes Historiques, led by Léon-Honoré Labande, an archivist for the Prince`s Palace. From 1910, Andre Corneau contributed professional reviews of theater, opera, and operetta performances in the La Vie Artistique (Artistic Life) section. On December 27 of the same year, the weekly expanded to eight pages to publish the full text of the Berlin Convention on the Protection of Literary Works, signed on November 13, 1908. This was approved and printed with Prince Albert`s permission.

From then on, government articles frequently increased the paper`s volume, though current affairs continued to occupy four pages. On January 7, 1911, a special issue appeared, featuring under the ornate headline Message (Message):

HRH Prince Albert

to the people of Monaco

"After 21 years of ruling my country according to ancient tradition, I have decided to grant the people of Monaco a constitutional government. This is not to demand rational benefits from this regime, for nowhere can prosperity akin to ours be found. But I wanted to show trust in the Monegasque people and prepare them to defend their interests should serious circumstances ever arise for the Principality".

The issue detailed the resolution and a report on the state of the principality across six pages. Monaco thus received its first constitution and a unicameral parliament, the National Council.

In January 1912, Aurèglia introduced a table of contents on the first page, clearly dividing the paper into sections:

- Partie Officielle

- Maison Souveraine

- Conseil National or Conseil Communaux

- Avis et Communaux

- Echos et Nouvelles

- La Vie Artistique

While poetry occasionally appeared, serialized novels had long been absent, except for excerpts in the Etudes Historiques column, which featured scientific works.

Two wartime pages of Journal de Monaco

The trajectory of the weekly, like all of Europe, changed in July 1914 when Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, triggering the "domino effect" of World War I. On August 1, France announced mobilization, and by August 3, it was drawn into the conflict. Monaco felt the ripple effects, with its citizens conscripted into the French army.

August issues carried safety advisories for residents (lock doors at night, avoid streets after dark), disruptions in communication with French cities, and vaccination notices. The paper published French government memoranda to Hague Convention signatories about German military actions.

On September 1, the weekly appeared with only two pages, featuring complaints from the French government, Prince Albert`s judicial decisions, and public notices (e.g., a public canteen was established). For weeks, the paper retained its two-page format, limiting regional news as the war took precedence.

On September 29, the subtitle Politics, Literature, and Art was replaced by Bulletin Officiel de la Principautè (Official Bulletin of the Principality), along with a new section, Etudes Economiques (Economic Studies), reviewing the principality`s economy. Once a month, the weekly expanded to four pages, often featuring advertisements. Despite the war and Monaco`s influx of refugees from France and Belgium, life gradually normalized.

During the war years, Journal de Monaco often faced paper shortages, limiting issues to two pages. Occasionally, four-page issues featured government decrees and announcements. Key topics included the principality`s economy and local history, covered by writers like Philippe Casimir. The paper avoided politics, gossip, and everyday matters unless related to the courts, port, or railways. However, it encouraged reading lighter publications with colorful illustrations and gossip, advertising these magazines and detailing how to purchase them. A notable feature was the printed records of parliamentary debates.

A 8-page bulletin, now published on thursdays

The summer of 1918 brought significant changes to the principality. The war was nearing its end, and in July, a treaty was signed between France and Monaco, which stipulated that the principality`s policies would align with France`s political, military, and economic interests.

As for the weekly, it entered the post-war era unchanged. It retained the same layout, editorial team, and leadership, with one notable difference: an increase in pages. The Journal frequently expanded to 6 or 8 pages, evolving into a serious bulletin. Cultural coverage focused solely on theater and opera, with casinos mentioned only in judicial and tax columns. The paper recommended books, though only those from the global market.

The National Council sessions, addressing the country`s pressing issues, generated significant interest, prompting the release of additional annexes. Two extensive supplements in December 1920 contained transcripts of all council meetings for the year. This practice continued in subsequent years.

For the next decade, Louis Aurèglia continued to manage the Journal de Monaco consistently, adhering to established norms despite the ascension of a new ruler, Louis II, on June 27, 1922. However, one change occurred: starting in April 1925, the weekly was published on Thursdays.

In February 1930, Charles Martini took over as editor-in-chief, leading from the Ministry of State. Martini managed the publication for 17 years, inheriting a stable yet stagnant position in the media market. Though the Journal served as the official government bulletin, Martini sought to introduce a breath of fresh air to the "old magazine". The La Vie Artistique (Artistic Life) column covered theatrical and operatic performances and significant classical music concerts, echoing the style of former contributor Andre Corneau.

The Avis & Communiques (News and Press Releases) section reported on important events in the principality, while Varietes highlighted the unique features of the small state. Despite its serious and official tone, the paper featured extensive advertisements promoting fashion, entertainment, and innovations such as cinema. At the year`s end, the Journal continued its tradition of publishing a special supplement summarizing council debates.

Another war, pages full of decrees

In 1933, the Journal began featuring photographs in its advertisements, showcasing art and architecture, which later extended to notable regional attractions.

Although Monaco operated under the watchful eye of France, its residents felt secure about their economy and future. In 1933, France relaxed anti-gambling laws, which affected Monaco`s economy. In response, Louis II focused on tourism and sports, lowering taxes to attract foreign investment. The Journal kept readers informed, ensuring a sense of calm.

Unfortunately, the late 1930s shook the principality alongside all of Europe as World War II erupted. On September 7, 1939, issue 4272 featured guidelines on air raid protocols, wartime living, and food shortages. Residents were advised to evacuate, foreigners faced special regulations, political meetings were banned under penalty of imprisonment, and privileges were revoked. Curfews required restaurants and cafes to close by midnight. Despite the cancellations of all events, December communications included details of New Year`s Eve and charity balls. Food prices reflected the war, with comprehensive weekly lists published.

For two years, the Journal primarily printed decrees, orders, and official announcements from Louis II, with only the Etudes Historiques (Historical Studies) section offering unrelated content, penned by A. Samosa Talbor. Monaco maintained official neutrality, but Louis II favored the Vichy regime, while the predominantly Italian population supported Mussolini, creating visible internal conflicts.

First the Italians, then the Germans

On November 11, 1942, Italian forces occupied Monaco. Within weeks, the Journal published supply directives for the occupying army. Cultural columns disappeared, replaced by legal and notarial notices, often concerning property transfers. Jewish residents, aware of the situation in Europe, began selling their assets.

The Germans replaced the Italians in September 1943 after Mussolini`s fall, initiating deportations of Jewish residents. Secret orders from Louis II, carried out by police at great personal risk, saved many lives. Nevertheless, the Journal reported on ongoing arrests.

German decrees prohibited radios, imposed food rationing, restricted fuel distribution (as noted in the October 7, 1943 issue), and closed casinos, shops, and pharmacies. Despite restrictions, the Journal continued publishing in French, with notices stating its availability in France and its colonies. French companies dominated advertisements.

The Germans withdrew from Monaco on September 3, 1944. A year later, in May, Europe celebrated the end of the war, while Louis II issued new regulations in the Journal to restore his small nation.

New look, new day, and a new address

On January 2, 1947, the Journal de Monaco debuted a revamped appearance, a new address, and a new publication day - Friday. The editorial and administrative offices moved to Place de la Visitation. The publication was restructured into two columns and categorized into sections:

- Louis II

- Sovereign Decrees

- Ministerial Orders

- Judicial Matters

- Municipal Decrees

- Social Services

- Economic Section

- Announcements and Notices

- Advertisements

The Journal de Monaco became a true government bulletin, ranging from 6 to 16 pages. Cultural and literary sections, as well as historical columns, were not reinstated. Such topics appeared in advertisements, often featuring photos of museums, theaters, opera houses, or exhibitions but only as part of promotional content.

Farewell to prince Louis II

On May 6, 1948, marking the 90th anniversary of the Journal de Monaco, a new editor-in-chief, Pierre Sosso, took the helm, bringing culture back to the publication. On November 29, 1948, Prince Louis II enacted Law No. 491 on the protection of literary and artistic works, and on December 27, the Informations Diverses (Various Information) section featured a review of a play performed at the Theatre des Beaux-Arts. From then on, at least one monthly article covered artistic activities in the principality.

Sosso led the Journal for 10 years and was responsible for announcing the death of Louis II. On May 9 and May 16, 1949, the front page of the Journal looked different. The first issue contained an article about the ruler`s death and an official government statement. The second page featured the deceased`s last will, dated April 28, 1949.

In the same issue, the heir to the throne, Rainier III, presented the budget for May and June along with other decisions. On May 16, the front page displayed a photograph of the late ruler, while the inner pages were filled with condolences from around the world. Until the end of May, the Journal continued publishing tributes to Louis II, but by June, normal content resumed.

On May 30, 1949, an advertisement announced: La Collection 1948 du Journal de Monaco présentée sous belle reliure, titre, or est en vente… (The 1948 Collection of the Journal de Monaco, presented in fine binding with a gold title, is now available...). This celebrated the paper`s 90th anniversary, with similar commemorative editions published in subsequent years.

Throughout the 1950s, the Journal de Monaco remained consistent in its operations. The prince issued decrees, the government and municipalities made announcements, and lawyers ensured the rule of law for citizens and businesses. The Informations Diverses column featured theater, opera, and cultural event reviews. The Journal reported on public expenditure, international affairs relevant to Monaco, and parliamentary legislation. Domestic news appeared in the Maison Souveraine (Sovereign House) section.

Grace Kelly and 100 years of the Journal

Monaco thrived under French influence, evident in notarial registers, tax reports, and tourism regulations. However, 1956 brought significant attention to the principality when Prince Rainier III married American actress Grace Kelly. The engagement, announced on January 5 in the U.S., was widely reported worldwide, and the Journal de Monaco published the official announcement on January 9. Civil ceremonies occurred on April 18, followed by religious ceremonies on April 19. To commemorate the event, a special April 19 issue featured a color cover of the couple and a 44-page report covering both ceremonies, guest lists, gifts, and congratulatory messages, complete with photographs documenting key moments.

On May 30, 1958, the Journal celebrated its centenary. However, the occasion was overshadowed by the birth of the princely couple`s first child, Alexandre. The milestone was organized under new editor-in-chief Camille Briffault, who assumed the role on April 21, 1958.

A year later, Monaco faced internal challenges as Rainier III suspended the National Council`s activities due to conflicts over the principality`s budget and other issues. On February 2, 1959, the Journal published Prince Rainier III’s Appeal to the People of Monaco, beginning with:

"What I have to tell you today is particularly important, and I wish for everyone to weigh my words and share with me the burden of responsibility at this hour. This concerns the present and future of the Principality. My duty is to ensure that our privileged status is preserved and that no one undermines our political and economic position. This morning, I was forced to take a difficult decision, and I feel obligated to inform you of its reasons because I owe you the truth. Driven to the limit by a hostile National Council, I am compelled to suspend our Constitution`s provisions and dissolve our parliament".

The prince justified his decision across two pages, and it remained effective until 1962, when parliamentary activities resumed, and a more liberal constitution was introduced. On December 31, 1959, the annual supplement titled Journal no. débats 1959 included a blank page with the note: assembly dissolved.

The new National Council and the country’s relaxed laws were covered by Charles Minazzolli, who became editor-in-chief on August 28, 1961, succeeding Raoul Biancherii, who served from May to July.

A government bulletin without advertisements

When Minazzolli took over, the Journal was published on Mondays. The editorial and administrative offices were housed in the Hotel du Gouvernément (Government Hotel), and the publication ranged from 8 to 48 pages, divided into seven sections:

- Maison Souveraine (Sovereign House, domestic news)

- Ordonnances Souveraine (Sovereign Ordinances, princely decrees)

- Arrêtés Ministériels (Ministerial Orders)

- Arrêté Municipal (Municipal Decrees)

- Avis et Communiqués (Notices and Press Releases)

- Informations Diverses (Various Information, cultural section)

- Insertions Légales Annonces (Legal Services and Announcements)

There were no advertisements or photographs. Each December, three additional editions were published:

- Journal, no Annexes... (year) summary of annexes

- Journal, no Débats... (year) summary of debates

- Journal, no Sommaires... (year) summary of all decrees

On December 17, 1962, Monaco’s new, more liberal constitution came into effect. It abolished the death penalty, granted women the right to vote, established the Supreme Court to guarantee fundamental freedoms, and made it harder for French citizens to establish residence in Monaco.

The full text of the constitution appeared in issue 5490 on December 24, 1962, with Prince Rainier introducing it:

"Considering that the principality`s institutions must be improved to meet the requirements of good governance and address new social needs, we have decided to equip the state with a new Constitution, which, according to Our Sovereign Will, shall henceforth be regarded as the fundamental law of the state and may only be amended under conditions we have established".

The National Council resumed its work. Article 66 of the new constitution stated:

"Legislation requires joint decision-making by the prince and the National Council. The legislative initiative belongs to the prince. Debates and votes on laws belong to the National Council. The prince sanctions legal acts, granting them binding force through publication".

On December 17, the Journal de Monaco was officially institutionalized. Article 69 stated that all protocols from public council sessions would be printed in the bulletin and come into effect the following day. The Journal came under the direct authority of the Government Secretariat General, with its head appointed as editor-in-chief, marking the end of editorial independence.

The first woman at the helm of the Journal

Charles Minazzolli led the Journal de Monaco until September 1979. During his tenure, he introduced the Lois (Law) section and returned the publication day to Friday. The parliament meticulously presented its financial reports, accounting for every franc spent. Maison Souveraine provided updates on the royal court, while municipal sections detailed planned investments and new hirings. The cultural section covered theatrical and operatic premieres as well as ceremonial concerts. Education, health, and social issues received substantial attention, always presented in the form of official announcements and notices. Similarly, the legal section informed readers about new businesses entering the market, bankruptcies, debts, and upcoming enforcement actions by bailiffs.

For the following decade, the editorial work of the Journal remained unchanged. Decrees, regulations, and announcements were the daily tasks of its editors, with only the leadership changing:

- In October 1979, Jean Ratti assumed the role of editor-in-chief.

- In July 1982, Pauline Migliardi took over.

- In October 1982, Marc Lanzerini assumed the position.

- In July 1985, Jean Claude Michel led the Journal.

- In June 1990, Rainier Imperti became editor-in-chief.

Pauline Migliardi, the first woman to hold the position, had the solemn duty of informing Monaco`s citizens about the death of Princess Grace on September 14, 1982, following a tragic car accident. The official government announcement appeared in the September 17 issue, along with details of the funeral scheduled for September 18.

Throughout the 1990s, Rainier Imperti led the Journal de Monaco from its offices at Place de la Visitation. During his tenure, the publication informed citizens of major events, such as Monaco’s accession to the United Nations in May 1993, the Journal`s 140th anniversary in May 1998, and plans for the new millennium in December 1999.

The Informations section introduced a new column, La Semaine en Principauté, Manifestations et spectacles divers (The Week in the Principality, Events and Performances), and another called Concours et recrutement (Competitions and Recruitment) for those seeking to advance their careers. The front page was updated to prominently display subscription fees and legal supplements. Despite being a government bulletin since 1962, the Journal remained accessible to all Monaco residents and even reached international subscribers. By 1995, the Journal could be delivered by air for a fee of 480 francs.

The turn of the millennium. Euros instead of francs

The late 1990s saw the rise of computers and the internet, a trend reflected in the Journal`s editorial office. However, the official online presence of the Journal wouldn’t launch until 2011. On January 1, 2001, Rainier Imperti handed over the reins to the new editor-in-chief, Giles Tonelli.

Although Monaco is not a member of the European Union, its close relationship with France grants it strong ties with the EU, including participation in the Schengen Area. From January 2002, the euro became the official currency in Monaco, as announced by the Journal, which also adjusted its pricing accordingly.

On April 2, 2002, the Journal published constitutional amendments, the most significant of which stated: "If there are no heirs to the dynasty, the Principality shall remain an independent nation and will not be annexed by France. However, France will continue to oversee Monaco`s military defense". This amendment resulted from a new treaty with France.

Giles Tonelli introduced several changes to the government bulletin. In December 2003, the Journal published its final annual supplements summarizing debates and decrees from the year. From then on, necessary information was released as standalone brochures rather than under the Journal`s masthead. The first such supplement, published in January 2004, detailed changes to tobacco product pricing under Ministerial Ordinance No. 2004-8.

Two years later, on May 30, 2004, Monaco experienced its first-ever bombing at AS Monaco’s football stadium. Thankfully, no one was harmed, though offices were damaged. To this day, the perpetrator remains unknown. The attack occurred three days after the team had been hosted at the Prince’s Palace for a private meeting with Rainier III (as reported in the June 2, 2004 issue).

On April 8, 2005, the front page of the Journal featured only an obituary for Rainier III, who passed away on April 6. His son, Albert II, succeeded him. A week later, the new prince published an open letter to the nation in both French and English. That same day, a special supplement titled Prince Rainier III: His Life, His Work was released, followed on April 22 by another supplement dedicated to Tributes and Funeral Ceremonies for Prince Rainier III.

Digitalization. The entire archive online

July 2006 marked another change in leadership for the Journal de Monaco. The new Secretary General, Robert Colle, upheld the traditions of the government bulletin while introducing systematic updates, such as improved printing, new columns, and adjustments to existing ones. Computers, which were instrumental in the editorial process, became central to organizing content. This technological advancement led to the establishment of the Advisory Committee on State Archives on August 29, 2011. One of its first decisions was to digitize historically or culturally significant documents from the government archives, including the Journal de Monaco. This initiative resulted in the creation of an official government website, which featured a dedicated section for the Journal.

The project took five years, culminating in September 2016 with the launch of the Journal`s official website, www.journaldemonaco.gouv.mc. This site includes all issues of the bulletin from its inception on May 30, 1858, updated regularly. The government website on September 15, 2016, stated:

"The search engine has been specially designed to allow users to search for laws and decrees by year, category, and topic. Full-text searches of historical and social events that took place in the Principality during the 19th and 20th centuries are also possible. Users can refine their search results using the `Narrow` option to find specific information. A version of the site for tablets and smartphones is also available, and the interface is offered in English".

While the print version of the Journal maintained its appearance and format as the official gazette, the website expanded its scope. It includes laws, decrees, and announcements, as well as a new Editos (Editorials) section. The first editorial, published on November 14, 2016, focused on National Day celebrations, which "date back to the reign of Prince Charles III, when the Principality became a modern state with a national flag, diplomatic representation abroad, and treaties signed with foreign powers".

Editorials cover state celebrations, anniversaries, and events such as the Monaco Grand Prix. The most recent, dated June 2, 2023, commemorated Rainier III with the theme: "The Centennial of the Prince`s Birth in a Sovereign Family". Most articles are accompanied by colorful photographs.

$1 trillion of global advertising market value 👇

The website quickly gained popularity as Monaco`s approximately 40,000 residents showed strong interest in their principality`s affairs. The print version is limited to 1,200 copies, making the online platform essential.

Between 2019 and 2021, Monaco, like the rest of the world, faced disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic. The Journal focused on printing decrees, orders, and decisions related to the crisis.

On February 4, 2022, an editorial celebrated the retirement of the head of the Journal de Monaco, stating:

"Mr. Robert COLLE, head of the Journal de Monaco, has been granted his retirement rights under Sovereign Decree No. 9.045 dated January 19, 2022. He will conclude his duties on February 6, 2022. The entire Journal de Monaco team wishes Mr. Robert Colle a wonderful and well-deserved retirement!"

The following day, Marc Vassallo assumed the role of Secretary General and head of the Journal.

In 2023, the Journal celebrated its 165th anniversary. Having started as a cultural weekly, it has undergone numerous changes but remains integral to Monaco`s life, appreciated and cherished by its citizens. The print version remains official, while the digital version is "more for the people", offering access to the entire archive - 8,655 issues as of August 11, 2023. Bravo!

Timeline of Journal de Monaco

- 1858, May 30 - First issue of the weekly L’Eden

- 1859, May 15 - L’Eden renamed Journal de Monaco

- 1859, November - Paris branch of the weekly established

- 1860, April 29 - 100th issue of the Journal

- 1861 - New office opened in Nice

- 1876, June 6 - Financial columns introduced

- 1877, August 28 - 1,000th issue of the Journal

- 1878, January - Sports column launched

- 1886, December 28 - First supplement (official matters)

- 1909, December 28 - First historical column

- 1911, January 7 - Special issue marking Monaco`s first constitution

- 1912, January - Changes to the Journal`s layout

- 1914, September 29 - Officially became Monaco`s government gazette

- 1920, December - Annex containing parliamentary debates introduced

- 1933 - First photographs published

- 1942, November 11 - Italian army occupied Monaco

- 1943, September - German forces entered Monaco

- 1947, January 2 - Changes to design, address, and publication day

- 1949, May 9 - Front page dedicated to the obituary of Louis II

- 1956, April 19 - Special issue with a color cover for Rainier III and Grace Kelly’s wedding

- 1958, May 30 - Journal’s centennial anniversary

- 1959, December 31 - Parliamentary debates supplement featured a blank page with the note "assembly dissolved"

- 1962, December 17 - Journal institutionalized under Monaco’s new constitution

- 2002, January - All fees converted to euros

- 2003, December - Final publication of annual supplements

- 2005, April 8 - Front page dedicated to Rainier III’s obituary

- 2005, April 15 - Special supplement celebrating the life and achievements of Rainier III

- 2011, August 29 - Advisory Committee on State Archives initiated the digitalization project

- 2012 - Journal made available online via the government website

- 2016, September - Official website launched with all issues dating back to 1858

- 2016, November 14 - First editorial published on the website

Sources:

- https://journaldemonaco.gouv.mc/A-propos-du-Journal-de-Monaco

- https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Journal_de_Monaco

- https://www.gouv.mc/monaco/search/(SearchText)/Journal+de+Monaco

- https://www.mediatheque.mc/Default/search.aspx?SC=DEFAULT&QUERY=Journal+de+Monaco+&QUERY_LABEL=#/Search/(query:(InitialSearch:!t,Page:0,PageRange:3,QueryString:`Journal%20de%20Monaco%20`,ResultSize:-1,ScenarioCode:DEFAULT,SearchContext:0,SearchLabel:``))

- https://journaldemonaco-gouv-mc.translate.goog/en/Journaux/1858?_x_tr_sl=en&_x_tr_tl=pl&_x_tr_hl=pl&_x_tr_pto=sc

- https://en.monacochannel.mc/Channels/Princely-Governement/News/All-issues-of-Journal-de-Monaco-now-online

- https://presselocaleancienne.bnf.fr/html/histoire-monaco

- https://mchercberg.com/2021/02/23/historia-monako-w-pigulce/

- https://wiadomosci.wp.pl/pierwszy-w-historii-zamach-bombowy-w-monako-6037491623031425a

COMMERCIAL BREAK

New articles in section History of the media

Jamal Khashoggi. A media trap, illusion of freedom, and price of free speech

Małgorzata Dwornik

He knew Osama bin Laden personally and advised Saudi kings, only to eventually become their greatest critic. Jamal Khashoggi entered the consulate in Istanbul and vanished without a trace, shocking world public opinion. This is the story of a man who traveled the path from palace salons to exile, paying the ultimate price for the fight for freedom of speech.

The History of The New York Times. All the news that's fit to print

Małgorzata Dwornik

In the heart of 19th-century New York, when news from across the world traveled via telegraph and the newspaper was the voice of public opinion, two ambitious journalists created a modest four-page daily that would eventually become a legend.

FORTUNE. The story of the most exclusive business magazine

Małgorzata Dwornik

Half of the pages in the pilot issue were left blank. Only one printing house in the country could meet the magazine’s quality standards. They coined the terms "business sociology" and "hedge fund". They created the world’s most prestigious company ranking. This is the story of Fortune.

See articles on a similar topic:

History of WSB Radio. The listener has no radio receiver? No problem!

Małgorzata Dwornik

The first transmitter had only 100 watts of power, and ice was used to cool the batteries. On March 15, 1922, the first radio station in Georgia began broadcasting. The station was assigned the call letters WSB, which the founders transformed into the motto: Welcome South, Brother! This marked the start of one of the most important radio stations in the USA.

Hind Nawfal and Al Fatat. The first women's magazine in the Arab world

Małgorzata Dwornik

The Egyptian phenomenon, founded by the "mother of female journalists", lasted only two years in the market. However, in that short time, it accomplished so much for Arab women that it is still called a "revolutionary" today. The Arab "Girl" and its founder were the first significant female voices in this culture.

History of The Honolulu Advertiser. From missionaries to a merger with rival

Małgorzata Dwornik

It was created to outdo unreliable competition. Early world news arrived via boat. It didn’t hire Mark Twain, but Jack London wrote for it. The story of Hawaii’s oldest newspaper spans 154 years of ups, downs, and radical changes in direction. In 2010, to survive a losing war of attrition with its biggest rival, it had to merge with it.

History of Le Soir. A Belgian daily once free for ground floor readers

Małgorzata Dwornik

It started with an unusual sales policy and articles written personally by the king. This is where the comic hero Tintin made his name. The "fake edition" from the II World War went down in history. "Le Soir" more than once found itself targeted by authorities, censors, and even... terrorists and hackers.