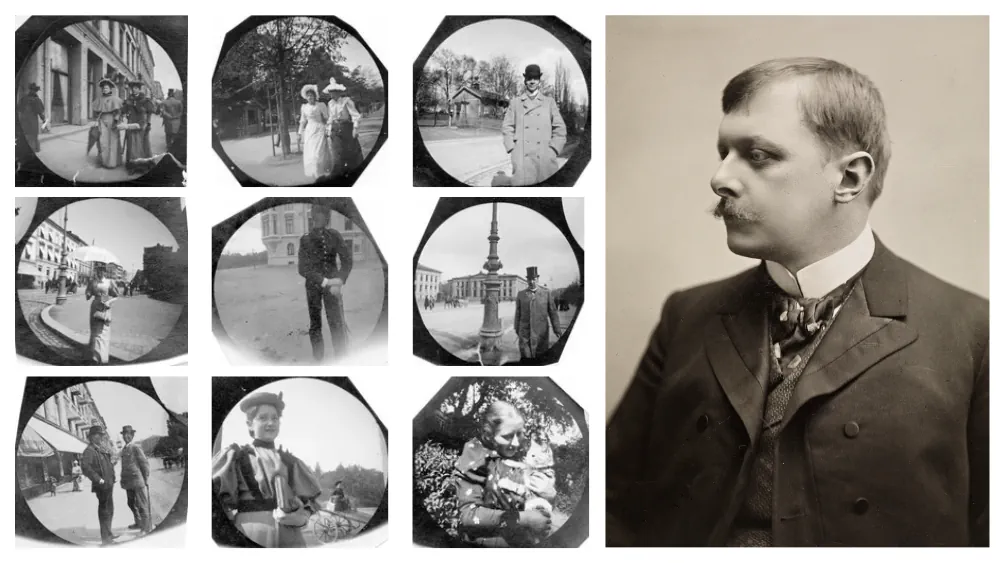

photo credit digitaltmuseum.no/public domain and Nasjonalbiblioteket/CC 2.0/Flickr

photo credit digitaltmuseum.no/public domain and Nasjonalbiblioteket/CC 2.0/FlickrAccording to Wikipedia, a photojournalist is a photographer specializing in capturing photos of current events (political, social, cultural, sports, etc.), and the first photo was taken in 1826 by French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, who captured a view from a window on a polished metal plate in Le Gras. Although Niépce built the device himself to create the world’s first photograph, the official invention of the camera is attributed to the Susse brothers in 1839.

The first photos, though considered a technological marvel, were of poor quality and static. The subject could not move. Only 67 years later, in Oslo, a 19-year-old mathematics student energized the Norwegian street, capturing passersby with a hidden camera. Today, he is celebrated as the world’s first photojournalist and paparazzo. His name was Fredrik Carl Mülertz Størmer.

Shyness and fascination. A combination that created a pioneer

Carl Størmer was born on September 3, 1874, in Skien, to pharmacist Georg Ludvig Størmer. His mother was Elisabeth Amalie Johanne Henriette Mülertz, and his father’s brother, inventor and engineer Henrik Christian Fredrik Størmer.

Henrik, childless himself, spent a lot of time with his curious nephew. His uncle`s interests and his father`s profession sparked young Carl’s curiosity in botany, astronomy, chemistry, and physics, but as a high school student, Carl dedicated most of his time to mathematics.

In 1892, Størmer entered the Royal Frederick University in Kristiania (now the University of Oslo) to study mathematics. Walking the streets of the capital, he observed people’s expressions, behaviors, and clothes.

He wondered how to preserve these scenes. Cameras at the time were large and static, yet Carl wanted to capture a specific moment, a smile, or a movement - especially of one young lady he admired. His youthful love, however, was no match for his shyness, which he couldn’t overcome, especially since he did not know the lady personally. He simply wanted her photograph. Easier said than done, but he had access to the latest inventions and his own genius.

Tesla’s selfies, Spaleterini’s balloons, and military technology

For some time, Nikola Tesla documented his inventions in a way we’d call selfies today, and Eduard Spaleterini captured bird’s-eye views during balloon flights. But how to take a hidden picture? That challenge was tackled by the military.

Spy cameras first emerged in 1888, although their size didn’t allow for discreet recording. By 1893, when the math student fell for the mysterious woman, miniaturization had become commonplace. Carl invested in a spy camera, the CP Stirn. He described it in an interview years later for the Hallvard Journal:

It was a round, flat container hidden under the vest, with a lens peeking through a buttonhole… A string ran from under my clothing through a hole into my pants pocket, and when I pulled the string, the camera took a picture… Six shots at a time, then I’d go home to change the plate.

This detective camera was quite well-known at the time. It came with a vest and was among the few successful models, produced in two sizes between 1886 and 1892. Størmer owned the smaller one.

He managed to capture a photo of the beautiful Norwegian, and told her many years later. The thrill of taking these photos fascinated him, and he made it a daily activity. Mornings were for university, and afternoons and weekends for strolling along Oslo’s main street, Carl Johan, taking photos of his fellow Norwegians. He took close to 500 photos, which were of high quality and circular, known as pinholes.

The Oslo paparazzo and 19th-century celebrity photos

Throughout his studies, Carl Størmer documented the streets of Oslo. People, their behavior, their joys and sorrows, their clothes and professions, along with transportation like carriages and rickshaws, and even seasons.

But the subject was always a person. Carl approached his subjects with a greeting, then snapped a photo. Depending on their response, he captured them smiling, discontent, tipping a hat, or eating cotton candy… Men, women, children, and animals.

1049 journalists in Europe silenced by lawsuits 👇

Later, he took his photography from the streets to meadows and rivers, capturing scenes from picnics, boat rides, and private gardens. The people of Oslo grew accustomed to the mischievous student with the spy vest, and even if Carl wasn’t wearing it, they’d smile and wave at him. Well, not everyone, as some felt uncomfortable when he stood in front of them and oddly fiddled in his pocket.

Still, smiles and good spirits were the norm. Among those he captured unknowingly were notable figures of the time. The playwright Henrik Ibsen, while not pleased to see young Størmer, and the botanist and linguist Ivar Aasen, along with physics professor Kristian Birkeland, were both smiling and friendly.

A paparazzo with academic achievements

While passionate about photography, Carl primarily focused on mathematics, achieving worldwide fame. During his studies, he published several works on number theory, and in 1897, he proved the Størmer’s Theorem (smooth number pairs boundary). He researched the Machin formula, which represents π as a rational combination, and also published several botanical papers.

He graduated in 1898 with the title candidatus realium, allowing him to study for five more years at the Sorbonne and Göttingen. In the meantime, in 1900, he began working at his alma mater and married Ada Clauson that February. They had five children (three sons and two daughters).

One might think that the settled, 29-year-old mathematician who became a professor in 1903 stopped playing with his camera, but not at all. Størmer quit street sessions, but his youthful passion stayed with him for life. Besides family photos, he used photography in his scientific work. Many of his later photos were published in Norwegian and international newspapers, all thanks to the aurora borealis.

The professor with a spy camera hunting the Aurora

In 1896, his classmate Bernt Birkeland proposed that auroras result from electrons emitted by the Sun. This idea intrigued Størmer so much that, alongside pure mathematics, it became the second path of inquiry and research for the brilliant Norwegian. In 1909, he began, as the first in the world, systematic aurora studies through photography.

- Observing the development of my photographic work may be of interest to many…such is often the case when a pure mathematician becomes an enthusiastic amateur photographer - he wrote about himself in his books.

However, when it came to aurora research, it’s hard to call it amateurish. The mathematician built a special high-sensitivity camera to capture the aurora and conduct studies based on the photos. He also used two cameras linked by a telephone line to calculate the height and width of auroras. He classified them all by shape and, in 1926, discovered a phenomenon called sunlit auroras. He also built his own aurora station. Over the years, he took nearly 40,000 photos.

In his book The Polar Aurora, published in 1955, he wrote: I found it necessary to gather more data on auroras to compare theory with observation. To this end, I developed and successfully applied a photographic method to determine the height and location of auroras. This book discusses the main results obtained from analyzing a vast number of parallax photos.

His publisher said of him: He was the first to develop precise photographic methods for calculating the height and morphology of different aurora forms over four solar cycles. His theoretical analyses explained the cosmic ray access to the upper atmosphere twenty years before others identified it.

7 facts about news on social media 👇

The aurora was not the only phenomenon Størmer studied. He used his cameras to observe:

- solar eclipses

- sunspots

- meteor tails

- clouds and their formations

All techniques and calculations proved highly useful in meteorology. He initiated a network of stations to study auroras and clouds, and his work was applied in studies on cosmic rays and their behavior near Earth. In 1934, he took a position at the Institute of Astrophysics in Oslo.

The coming out of a 70-year-old

By the end of the 19th century, photos were already widely known. Although the first press photo appeared in 1839, it was mostly an expensive novelty, and newspapers rarely published photos. If visual information was needed, it was often conveyed through engravings and illustrations. For this reason, Carl Størmer’s photos remained in family albums. Between 1942 and 1943, he shared a small portion of his work with the public, but only at 70 did he hold an exhibition displaying all his historical photos.

He retired in 1945 at 71 and dedicated himself to writing. His research, photographs, and achievements were compiled in the book The Polar Aurora, his second publication. His first book, published in 1923, titled From the Depth of Space to the Inside of the Atom, was translated into several languages and brought him remarkable success.

Many universities honored his work with awards and titles. His homeland didn’t forget him either. In 1902, he received the King Oscar II’s Gold Medal of Merit. In 1939, he was awarded the Knight of the First Order of Saint Olaf, and in 1954, he was given the Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Olaf.

Throughout his life, Carl Størmer sought, inquired, and proved. He published his reflections, experiences, and theories not only in specialized journals like Terrestrial Magnetism and Atmospheric Electricity (1930) and Transactions of the American Geophysical Union (1957) but also in widely accessible newspapers and magazines. He wrote about not only mathematics and auroras but also biology, the cosmos, and astrophotography. Whenever possible, he included evidence in the form of a photo he took himself.

He lectured at universities in Norway, France, Switzerland, and Germany. He was a mathematician, researcher, professor, president of the Norwegian Mathematical Society, and a talented photographer. When he displayed photos from fifty years prior in celebration of his 70th birthday, some were astounded. They saw not only documents of the late 19th century in excellent quality but also images of their ancestors. Størmer was celebrated as a pioneer of street photography and the first photojournalist.

Most of his photos from 1893-1897 can be viewed at the Norwegian Digital Museum [view photos]

Carl Størmer passed away on August 13, 1957, at 83. In 1971, a crater on the Moon’s far side was named after him.

Timeline:

- 1874, September 3 - Fredrik Carl Mülertz Størmer is born

- 1892 - 1897 - studies at the Royal University in Kristiania, now Oslo

- 1893 - 1897 - street photography sessions by student Størmer

- 1897 - mathematician proved "Størmer’s Theorem"

- 1898-1903 - studies in Paris and Göttingen

- 1900 - Størmer began working at the University of Oslo in the math department

- 1900, February - Carl Størmer married

- 1902 - awarded the King Oscar II’s Gold Medal of Merit

- 1903 - the young husband received the title of professor of pure mathematics

- 1909 - Størmer built a special camera to photograph auroras

- 1909 - 1943 - aurora research through photography

- 1923 - the book "From the Depth of Space to the Inside of the Atom" was published

- 1926 - discovery of "sunlit auroras" phenomenon

- 1934 - Størmer began work at the Institute of Astrophysics

- 1939 - awarded the Knight of the First Order of Saint Olaf

- 1944 - 70th birthday exhibition of Størmer’s photos from 1893-1897

- 1945 - well-deserved retirement

- 1954 - awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Saint Olaf for his lifetime work

- 1955 - the book "The Polar Aurora" was published

- 1957, August 13 - Carl Størmer passed away

- 1971 - a crater on the Moon’s far side was named after him.

sources:

- https://racingnelliebly.com/weirdscience/carl-stormer-victorian-era-spy-camera/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_St%C3%B8rmer

- https://pl.pinterest.com/pin/588916088745987960/

- https://monovisions.com/vintage-street-shots-of-oslo-by-carl-stormer-1890s/

- https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Stormer/

- https://www.donttakepictures.com/dtp-blog/2019/7/10/8womh2wezwu4b62qzg81lrtd7qbj39

- https://www.swiatobrazu.pl/mobile/zdjecia-xix-wiecznego-oslo-wykonane-potajemnie-za-pomoca-aparatu-ukrytego-pod-plaszczem-36745.html

- https://fotoblogia.pl/carl-st-rmer-robil-zdjecia-z-ukrycia-w-xix-wieku-czy-byl-pierwszym-fotografem-ulicznym,6793586429778049a

- https://kultura.onet.pl/sztuka/19-letni-student-krazyl-po-xix-wiecznym-oslo-z-aparatem-szpiegowskim-ukrytym-w/t3447zt

- https://impa.br/en_US/noticias/carl-stormer-1874-1957-mathematician-and-paparazzo/

- https://www.fotopolis.pl/inspiracje/znani-fotografowie/29749-pierwszy-paparazzo-na-swiecie-niecodzienne-hobby-nastolatka-z-xix-wiecznej-norwegii

- https://web.archive.org/web/20051217145614/http://www.norsk-teknisk.museum.no/wormpetersen/stormerbiografi.htm

- https://nrk.no/kultur/xl/carl-stormer_-studenten-som-snikfotograferte-ibsen-1.15501709

- https://britannica.com/biography/Frederik-Stormer

COMMERCIAL BREAK

New articles in section History of the media

Jamal Khashoggi. A media trap, illusion of freedom, and price of free speech

Małgorzata Dwornik

He knew Osama bin Laden personally and advised Saudi kings, only to eventually become their greatest critic. Jamal Khashoggi entered the consulate in Istanbul and vanished without a trace, shocking world public opinion. This is the story of a man who traveled the path from palace salons to exile, paying the ultimate price for the fight for freedom of speech.

The History of The New York Times. All the news that's fit to print

Małgorzata Dwornik

In the heart of 19th-century New York, when news from across the world traveled via telegraph and the newspaper was the voice of public opinion, two ambitious journalists created a modest four-page daily that would eventually become a legend.

FORTUNE. The story of the most exclusive business magazine

Małgorzata Dwornik

Half of the pages in the pilot issue were left blank. Only one printing house in the country could meet the magazine’s quality standards. They coined the terms "business sociology" and "hedge fund". They created the world’s most prestigious company ranking. This is the story of Fortune.

See articles on a similar topic:

The History of Radio Broadcasting

Agnieszka Osińska

Radio emerged almost simultaneously with film at the dawn of the 20th century, as the growth of the press pushed culture past the so-called second threshold of mass distribution. Alexander Popov and Guglielmo Marconi are considered its pioneers, though only Marconi succeeded in patenting the invention.

Radio Tirana. History of a broadcasting station founded by royal decree

Małgorzata Dwornik

On November 28, 1938, King Zogu I and his wife, Queen Geraldine, officially inaugurated Albania's first radio station. Radio Tirana kept its origins a secret for decades. When it finally revealed its early history, the revelation surprised not only listeners but even its own staff.

Reporters Without Borders. The history of Reporters Sans Frontières

Małgorzata Dwornik

In June 1985, in Montpellier, France, four journalists inspired by the work of Médecins Sans Frontières decided to create a similar organization in the media world. Today, RSF has 134 correspondents worldwide, with many successes... and controversies.

Dorothy Day story. Journalist, feminist and saint candidate

Małgorzata Dwornik

She fought poverty with fire, defied war with silence, and prayed with clenched fists. Dorothy Day, once a communist and always a fighter, now walks the path to sainthood. Her journey from rebellion to devotion still divides and inspires. This is the story of "the rebel saint".