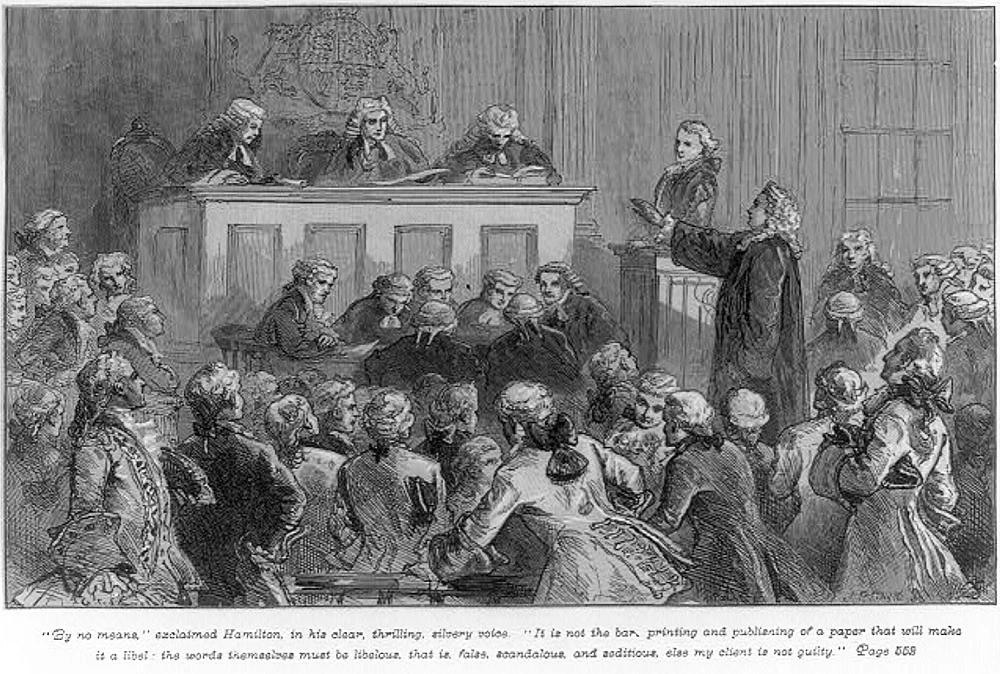

Andrew Hamilton defends John Peter Zenger in court, 1734-1735. Source: Library of Congress USA, public domain

Andrew Hamilton defends John Peter Zenger in court, 1734-1735. Source: Library of Congress USA, public domainOn October 26, 1697, in the German village of Rumbach, part of the Palatinate, a boy named John Peter was born to Nicolaus Eberhard Zenger, a teacher, and his wife Johanna. He was their firstborn, and over the next nine years, Johanna gave birth to three more children.

John grew up in a happy family. His father, a teacher, ensured the children received a good education. In 1710, the Zenger family emigrated to North America with a group of fellow countrymen.

The journey took them through London, and in April, only five Zengers boarded the ship. One child did not survive the first leg of the trip. Tragically, after two months at sea, Johanna arrived in New York as a widow. Nicolaus was lost to the ocean.

At thirteen, John had to take care of his mother and siblings. The then-governor of New York, Robert Hunter, supported European immigrants by organizing apprenticeships. In October 1710, young Zenger began his first job with William Bradford, New York’s only printer.

Maryland and Mary White

The contract required John to work in the print shop until he reached adulthood, totaling eight years. During this time, he mastered typesetting, printing techniques, the English language, and business management. Printing fascinated him, and he eagerly learned its intricacies.

After eight years, Zenger moved to Maryland’s eastern shore to establish his own print shop and collaborate with local authorities. On July 28, 1719, he married Mary White.

Unfortunately, his Maryland venture did not succeed. Without government contracts, his print shop failed to secure work. Adding to his misfortunes, he became a widower. Returning to New York, he resumed work at Bradford’s print shop. This time, fortune smiled on him. On September 11, 1722, he remarried, choosing Anna Catherine Maulin as his wife.

The first newspaper in New York

John’s work at the print shop occupied much of the Zenger family’s time, which quickly grew with the addition of children. But when William Bradford began printing the first and only New York newspaper, the New York Gazette, in 1725, Zenger fully immersed himself in the endeavor, even becoming a partner in the business.

The following year, in 1726, he took another gamble, investing in his own print shop. It was a bold move, as Bradford, known as the King of Printing, monopolized government and religious printing - critical to any print shop’s survival at the time.

Despite the challenges, Peter Zenger persevered. By 1731, his print shop on Smith Street was producing 21 publications (compared to Bradford’s 50). His fortunes improved in 1730 when he published Peter Venema’s book Arithmetica, recognized as the first arithmetic text printed in New York.

For seven years, John Peter Zenger competed with his former employer. He earned a reputation as a reliable craftsman, and his modest business sustained his large family. However, the 36-year-old publisher could not foresee the upheaval a decision in late 1733 would bring to his life.

The New York Weekly Journal

On August 1, 1732, William Cosby, a brash and vulgar individual, was appointed governor of New York. Before his arrival, his duties were handled for 13 months by Rip Van Dam, a senior merchant. Upon taking office, Cosby demanded half of Van Dam’s earnings during that period, to which Van Dam agreed, provided Cosby share his own income from the same time. The conflict escalated to the Supreme Court of Administration. Representing Van Dam were attorneys William Smith and James Alexander, while Chief Justice Lewis Morris ruled in favor of the merchant, citing British law. He publicly announced his decision, infuriating Cosby, who dismissed Morris and replaced him with an ally.

The conflict and trial were covered in the New York Gazette, which supported Cosby. The attorneys Smith, Alexander, and Morris, all members of the People’s Party, opposed the governor’s abuses and decided to launch their own newspaper to challenge him. They approached Peter Zenger as their publisher, and he eagerly agreed.

On November 5, 1733, New Yorkers received a second newspaper in the city: the independent weekly The New York Weekly Journal. James Alexander became the chief editor. Zenger was responsible for printing, document management, and contributing articles. William Smith and Lewis Morris formed the rest of the editorial team.

The New York Weekly Journal featured four pages, two columns, and the header: Containing the freshest Advices, Foreign and Domestic. It included current articles, advertisements on the last page, satire, poetry, and essays, with sections separated by decorative borders.

On the warpath with the governor

The Journal was published every Monday, primarily attacking Cosby’s government, his supporters, and exposing corruption. With many opposing the governor, the newspaper quickly gained popularity.

Articles were anonymous, often using pseudonyms. Only Zenger’s name appeared openly. Editorial pieces often began as letters to the publisher, such as: Mr. Zenger, your article in Issue V, December 2, claiming Cape Britton residents faced supply shortages... This December 17, 1733, piece criticized the government’s ineptitude and secrecy, as covered in the New York Gazette.

Articles addressing social, religious, or political matters invariably targeted the governor’s administration. Although Zenger’s name frequently appeared, whether he authored the articles remained unclear.

The paper’s audience included Dutch immigrants who harbored resentment against British rule since losing their New Amsterdam colony in 1644. This community, often mistreated by authorities, found a voice in the Journal, which openly criticized such injustices. Zenger’s wife, a Dutchwoman, supported him in his work.

Prophetic Cato’s Letters

Much space in the years 1733-1735 was devoted to the War of the Polish Succession. This conflict in Europe involved coalitions of France, Spain, and Bavaria against Austria, Russia, Prussia, and Denmark, fighting over the Polish throne and territories in Germany and Italy. Reports of these events were always extensive, given that many New Yorkers at the time were immigrants from those nations.

The weekly was often referred to as the "Zenger Gazette", and while the editorial board consisted of four members, Alexander took the lead. With his extensive knowledge of law and freedom of speech, he drew on contemporary philosophers in his articles. This was evident in pieces inspired by the duo John Trenchard and Thomas Gordon, who wrote essays under the pseudonym CATO. Their famous Cato’s Letters on defamation appeared in the Journal on February 25, 1733, and proved prophetic.

This peculiar date is one of many misleading ones on the paper’s front page, due to the calendar in use at the time. According to Wikipedia: At the time, Britain and its colonies followed a calendar system where January, February, and part of March retained the previous year’s date. This system was abolished in the 1750s. Therefore, the Cato essay (which caused a significant stir) was published on February 25, 1734.

Throughout 1734, Cosby fought against the weekly. He knew who was behind the articles attacking him but could not prove it. He focused his wrath on Peter Zenger.

The conflict began on January 28, with an article accusing the governor of endangering freedom and property. In response, the Gazette printed Cosby’s statement on defamation of authority. In September, two consecutive issues of the Journal accused the governor of violating his office’s rules. Cosby filed a lawsuit, but the court dismissed it. On October 22, the governor again petitioned the court, this time demanding the public burning of the weekly at the city’s pillory. The court dismissed this too. On November 2, Cosby personally destroyed the entire circulation of The New York Weekly Journal by burning it at City Hall on Wall Street, and he ordered the arrest of the only publicly known editor and publisher of the paper - Peter Zenger.

The publisher behind bars. Working through a keyhole

On November 17, 1734, Zenger was imprisoned. The bail amount was beyond his means, though his partners could afford it. However, they decided to proceed with a trial. Zenger’s defense attorneys were, of course, the Journal editors William Smith and James Alexander. The governor kept pressing, presenting new charges against the weekly and accusing Zenger, Alexander, and even Van Dam of libel. In December, Justice Lewis Morris traveled to London with a list of grievances against Cosby.

Meanwhile, Zenger managed the paper from prison, where it continued to be published and attacked the government. His wife took over his duties. During her visits through the keyhole (literally), she received instructions on weekly topics. The editors wrote the articles, and Anna printed them. Except for a gap in publication the Monday following his arrest, the Journal was issued regularly.

By November 25, 1734, Zenger wrote about his arrest: Since last week you were disappointed by the absence of my Journal, I feel it is my duty to publish an apology, namely this. On the Lord’s Day, the seventeenth, I was arrested, taken, and imprisoned in the common jail of this city by order of the governor and other members of the council, during which I was subjected to restrictions so severe that I could not use pen, ink, or paper, nor meet or converse with anyone until I lodged a complaint with the honorable Chief Justice (...), after which I was allowed to speak through a hole in the door to my wife and servants. Thus, I hope you will consider this a sufficient excuse for the absence of last week’s journal.

Zenger spent ten months in prison, working through the keyhole. During this time, both New York newspapers reported on the delays in starting the trial. The news spread to other cities and their presses, turning the case into a major story.

The governor triumphs. Zenger goes to trial

Cosby continued facing attacks in the press, alongside other troublesome topics. On May 19, 1735, an article on women’s education appeared, a scandalous issue for many at the time. The author argued that a woman’s domestic lifestyle better suited her to learning than a man’s way of life, and women’s natural gift for speech could be better utilized in education than in idle gossip.

A month later, on July 14, another article declared that resistance is necessary to preserve and protect the natural rights of equality and self-preservation. It warned against yielding to corrupt authority and those who consider themselves above the law.

Such articles appeared in nearly every issue, addressing issues like children’s rights, legal violations, or slavery.

Cosby persistently hindered Zenger’s lawyers, delaying the trial and leading to the removal of Alexander and Smith. Despite a pre-trial jury refusing to indict the publisher, the governor found a legal loophole. On August 4, 1735, Zenger faced New York’s Supreme Court. Frustrated by repeated rejections of defense attorneys, Zenger requested young lawyer John Chambers, who, like most attorneys, was aligned with the government.

Zenger acquitted. The work of two remarkable lawyers

Expecting the worst, Zenger’s friends brought in Andrew Hamilton, a prominent lawyer from Philadelphia. Meanwhile, Chambers demonstrated professionalism and fairness. He pointed out flaws in the indictment, irregularities in jury selection, and the baselessness of the charges. Hamilton, initially observing from the gallery, was impressed. However, he delivered the closing argument, excelling in his role. He argued that the jury could reach a verdict independently, so the judge (a government ally) need not heavily influence the proceedings. Hamilton admitted Zenger printed the articles but declared, People who oppress and harm a nation under their administration provoke cries and complaints, only to use these very grievances as grounds for further persecution.

He posed two questions:

- Should articles, if true, be considered libel?

- Is the ability to expose corrupt public officials not a cornerstone of liberty?

Referring to Cato’s earlier writings, Hamilton concluded: These questions, gentlemen of the jury, are not minor or private matters. This is not merely about one poor printer or New York alone. NO! The consequences may affect every free man living under British rule in America. This is the ultimate cause - freedom’s cause.

Fifteen minutes later, the jury announced the verdict: not guilty. Zenger was free. The courtroom erupted in applause and cheers, which spilled into the streets as New Yorkers celebrated Zenger and his newspaper.

Legal changes across the British Empire

The trial of a New York printer for libel echoed widely, not only in America but also in Europe, particularly within the British Crown. It forced English authorities, especially those in the colonies, to amend libel laws. The case proved that truth is an absolute defense against libel and that press freedom is as essential as air. This trial was the first and most significant step toward that principle. It also demonstrated the independence of professional lawyers and strengthened the jury’s role as a check on executive power.

Zenger, though not seeking fame, became a symbol of the fight for press freedom. The trial brought renown to other actors in the drama, though not all, such as Cosby, in a positive way.

Upon returning home, Zenger chronicled his time in prison and the trial in subsequent issues of The New York Weekly Journal. The first installment of the series was published on September 18, 1735, including Zenger’s official thanks to his defenders. He also expressed gratitude to the jury, listing all jurors by name. Subsequent issues, with the help of James Alexander, detailed the trial proceedings, speeches, and lawyer dialogues. New York buzzed about the event for a long time.

On March 10, 1736, Governor Cosby passed away, and two years later, in 1738, Justice Lewis Morris, co-founder of the Journal, became New Jersey’s first governor.

Peter Zenger continued to write about these and other significant events for years in his weekly. Starting in 1737, he worked for the government in New York’s district, replacing his teacher and competitor Bradford. When Morris became governor, Zenger served as a printer for New Jersey as well. The governor called him the morning star of our nation’s liberty.

Eternal fame. A Bronx monument, a street in Frankfurt

This "morning star" continued to lead the Journal for another decade but stepped back from aggressive political battles. Even when government missteps occurred, they were pointed out but not with the ferocity seen during Cosby’s time. The paper became more practical and standard, focusing on the daily lives of New Yorkers, the Crown’s war with France, and correspondence from various American cities. Most foreign news was reprinted from Boston newspapers.

Though The New York Weekly Journal became less combative, it remained a popular and well-loved publication. Peter Zenger ran it until his death on July 28, 1746, at the age of 48. His wife, and later his eldest son, took over the operation. The paper continued until March 18, 1751.

Nearly 289 years after the Zenger Trial, the modest printer’s legacy is deeply rooted in American history. His memory lives on in society to this day. A monument to Zenger stands in the Bronx, New York, created by Polish-American sculptor Józef Kisielewski. During World War II, a Liberty ship named SS Peter Zenger sailed the oceans, and in Madison, a 20th-century underground newspaper called Zenger was published.

Zenger News is a news service run by journalists. In Frankfurt, there is a street named after him, and at the Federal Hall National Monument on Wall Street in New York, a replica of the printing press he used for his weekly is displayed.

Peter and his wife were also the subjects of an episode of the television show Studio One. It premiered on January 12, 1953, with Eddie Albert portraying the publisher.

As noted by a journalist from the patriottoursnyc.com portal: This is a strange story about how a financial dispute combined with lawyers, a corrupt governor, and a hardworking printer laid the foundation for our freedom of the press. As I’ve said: only in America!

John Peter Zenger’s timeline

- 1697, October 26 - John Peter Zenger is born

- 1710 - The Zenger family emigrates to America

- 1710, October - Zenger begins his first job at Bradford’s print shop in New York

- 1718 - Zenger moves to the East Coast and starts his own print shop

- 1719, July 28 - Zenger marries Mary Withe

- 1720 - Zenger returns to New York and resumes working at Bradford’s print shop

- 1722, September 11 - Zenger marries Anna Katharina Maulin

- 1725 - Zenger becomes Bradford’s partner and co-publisher of New York’s first newspaper, the "New York Gazette"

- 1726 - Zenger opens his own print shop in New York

- 1730 - Zenger’s print shop publishes "Arithmetica" by Peter Venema, the first math book printed in New York

- 1733, November 5 - The first issue of "The New York Weekly Journal" is published

- 1734, January 28 - Conflict between Governor Cosby and Zenger begins

- 1734, September - Zenger is first accused of libel

- 1734, October 2 - The entire print run of "The New York Weekly Journal" is burned in front of New York City Hall

- 1734, November 17 - Peter Zenger is arrested

- 1734, November 17 - August 4, 1735 - Zenger directs the publication of the newspaper from prison

- 1735, August 4 - The libel trial of Peter Zenger begins

- 1735, September 18 - The first installment of Zenger’s account of his imprisonment and trial is published

- 1737 - Zenger and his Journal begin working for the government in New York’s district

- 1738 - Zenger becomes a printer and publisher for New Jersey

- 1746, July 28 - Peter Zenger passes away

- 1751, March 18 - The final issue of The New York Weekly Journal is published

Sources:

- https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/john-peter-zenger/

- https://history.nycourts.gov/case/crown-v-zenger/

- https://www.britannica.com/topic/New-York-Weekly-Journal

- https://www.gilderlehrman.org/collection/glc07336

- https://www.nps.gov/feha/learn/historyculture/the-new-york-weekly-journal-and-the-arrest-of-john-peter-zenger.htm

- https://www.gilderlehrman.org/collection/glc08724

- https://www.famous-trials.com/zenger/100-readings

- https://www.gutenberg.org/files/54836/54836-h/54836-h.htm

- https://www.oakknoll.com/pages/books/42175/stephen-botein/mr-zengers-malice-and-falshood-six-issues-of-the-new-york-weekly-journal-1733-34

- https://hansandcassady.org/Truth-Is-MY-defense.html

- https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=3&psid=92

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?app=desktop&v=L3kljrvMVh8

- https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/documents/new-york-weekly-journal/

- https://www.famous-trials.com/zenger/89-record

- https://digitalcollections.nyhistory.org/islandora/object/nyhs%3A235250

- https://www.famous-trials.com/zenger/92-chronology

- https://www.gutenberg.org/files/54836/54836-h/54836-h.htm

- https://www.immigrantentrepreneurship.org/entries/john-peter-zenger/

- https://www.varsitytutors.com/earlyamerica/bookmarks/peter-zenger-freedom-press

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Peter_Zenger

- https://archive.org/details/StudioOneTheTrialOfJohnPeterZengerPaulNickell

COMMERCIAL BREAK

New articles in section History of the media

Jamal Khashoggi. A media trap, illusion of freedom, and price of free speech

Małgorzata Dwornik

He knew Osama bin Laden personally and advised Saudi kings, only to eventually become their greatest critic. Jamal Khashoggi entered the consulate in Istanbul and vanished without a trace, shocking world public opinion. This is the story of a man who traveled the path from palace salons to exile, paying the ultimate price for the fight for freedom of speech.

The History of The New York Times. All the news that's fit to print

Małgorzata Dwornik

In the heart of 19th-century New York, when news from across the world traveled via telegraph and the newspaper was the voice of public opinion, two ambitious journalists created a modest four-page daily that would eventually become a legend.

FORTUNE. The story of the most exclusive business magazine

Małgorzata Dwornik

Half of the pages in the pilot issue were left blank. Only one printing house in the country could meet the magazine’s quality standards. They coined the terms "business sociology" and "hedge fund". They created the world’s most prestigious company ranking. This is the story of Fortune.

See articles on a similar topic:

History of The Honolulu Advertiser. From missionaries to a merger with rival

Małgorzata Dwornik

It was created to outdo unreliable competition. Early world news arrived via boat. It didn’t hire Mark Twain, but Jack London wrote for it. The story of Hawaii’s oldest newspaper spans 154 years of ups, downs, and radical changes in direction. In 2010, to survive a losing war of attrition with its biggest rival, it had to merge with it.

Tibetan Review. The story of a media warrior for Tibetan freedom

Małgorzata Dwornik

In 2023, it will celebrate its 55th birthday. The small editorial team is an important part of Tibetan democracy in exile. And thanks to its permanent move from print to the internet, Tibetan Review now brings news about Tibet to the farthest corners of the world.

Control is Better

Ignacio Ramonet

The noblest duty of media professionals is to expose cases of law violations. For fulfilling this duty, they have often had to pay a high price. However, for a long time, citizens - at least in democratic societies - could rely on the press and other media in their fight against abuses of power.

South Wales Echo. History of a Welsh paper with its own tabloid vision

Małgorzata Dwornik

Give people the facts briefly, but make sure they are facts - this was the guiding principle set by the founder David Duncan when the paper was established in 1880. South Wales Echo stayed true to this motto even a century later when it became a tabloid. A unique one, because it prioritized local affairs over sensationalism. It actively engaged in regional life and social campaigns. It even created its own beer brand.